01 Feb History: Noble Horseman

In 1914, as the silent-movie wave swept the nation, Hollywood’s biggest character was Jim Stokes, the Two-Gun Man. In the film The Bargain, Jim wore a six-shooter on each thigh, rolled his cigarettes one-handed, and rode a brown-and-white pinto named Fritz. He was the good bad man in a storyline with morality to match the action.

That fame also enveloped the actor who portrayed him: William S. Hart. Hart worked clean shaven and without makeup. No false whiskers needed, he embodied the authentic man of the West. His brave but sexless masculinity allowed young women (and their parents) to perceive him as safe, and men to find him non-threatening. He became the template for celluloid cowboy heroes that remains to this day.

Hart’s own story, his rise and fall, has a theatricality that would be marvelously fitting if it didn’t feel so tragic. But, like a country music song, it ends with a sort of redemption — and a surprising Montana twist.

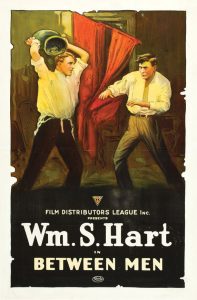

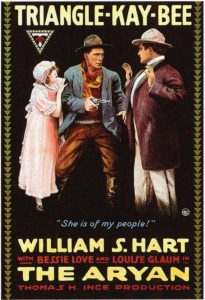

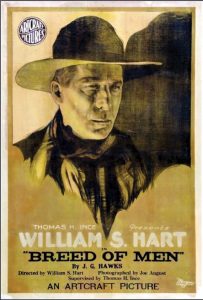

NeHart’s unadorned face created the template for the noble cowboy hero in 50 movies across seven years, including those pictured in the posters above, right, and below.

Born in Newburgh, New York, in 1864, Hart bounced around as a kid, with family homes in Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Texas, and the Dakotas. As an adult, he discovered the stage and spent his 20s and 30s as an itinerant actor. In 1903, he was sharing a room in New York with another actor, Thomas Ince. They struggled to make the $9.50 weekly rent, subsisting on stale bread, tinned beans, and Hart’s stories of the Sioux people he’d known as a kid.

In 1914, Hart went on tour with a play called The Trail of the Lonesome Pine. When it reached Los Angeles, he called on his old friend Ince, now a movie producer. Ince had been filming Westerns in the Santa Monica mountains, and Hart fell in love with the setup. Hart wanted to become a Western film star. Ince, skeptical, pointed out that Hart was already 50 years old. How about directing? No. Hart was convinced that audiences hungered for his stage persona: his 6-foot-2 frame, noble face, and Western knowledge.

He was right. The following year, Hart became the biggest money-making star in the country. Hart’s deeply moral characters were always clever and charismatic. His sad-faced cowboy made bold decisions and stoically lived with the consequences. His movies also captured a look and feel. In outdoor scenes, landscape was always essential to the action, never just a backdrop. Indoor scenes were marked by gritty realism, with plenty of dust.

Hart succeeded by authentically capturing details. To help, he could turn to the many Western figures then living in southern California. He befriended Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, Luther Standing Bear, and Charles M. Russell.

Hart, third from right, was a cast member of a 1914 play called The Trail of the Lonesome Pine when, at age 50, he decided to conquer Hollywood.

At his peak, Hart was one of Hollywood’s most eligible bachelors. He lived with his chronically ill sister, Mary, on a ranch in the Santa Clarita Valley. On December 7, 1921, he married a blue-eyed blonde that he’d met on a movie set. She was 22 years old. He was 57.

About five months after the wedding, Hart ordered his wife out of his house. The command followed a conference with his sister, and was issued in the presence of guests. His wife didn’t believe him until he repeated himself. She was pregnant with his child. The press had a field day. Hart had always been a moralistic figure, even a prude. So, as the divorce dragged on for years, stories delighted in allegations of abuse and parsimony. Worse, Hart had not borne fame well. He’d broken with Ince, unhappily. His ego infuriated other producers. Later, he would rant that “the Hollywood Jews” had ruined him.

Hart thought he was the story. He considered himself the face of Manifest Destiny. He became increasingly dogmatic about his nostalgia-laden views of history. But did Hart embody Western authenticity, or did he just fake it well? True, his youth had been poor and rootless, his father distant and hypermasculine. Still, unless you count boyhood farm chores, neither had been frontiersmen. They hadn’t run cattle on the open range or confronted danger on a lonely prairie.

After 50 Hart films in seven years, audiences were ready for something different. They gravitated toward stars like Tom Mix and Hoot Gibson. These former rodeo performers offered more action and flashier costumes — after all, this was entertainment, not a documentary. Comedians Fatty Arbuckle and Buster Keaton mocked Hart’s wooden acting style. Critics agreed. In 1925, a newspaperman noted that Hart’s “staple pose of ‘looking noble’” was “about as dynamic as the Indian head on the Buffalo nickel.”

Hart reacted to adversity with what he must have thought was stoic, stubborn determination. “They tell me Western pictures are no longer popular,” he said. “They told me that when I first came to Hollywood in 1914. I didn’t believe it then, I don’t believe it now.”

Hart’s sad face combined with authentic, even dusty, interiors to create a unique look and feel to his movies.

His last great epic Western, Tumbleweeds, was a failure. As Hart sued his distributor for the money it would have made, he knew his movie career was finished. He tried books, but his novels — such as the 1922 Injun and Whitey to the Rescue — were full of lame stereotypes. They lacked the very authenticity of detail that he claimed to value. Hart eventually came to believe that publishers, like studios, had mistreated him. He became ever more “self-absorbed and pessimistic” writes Ronald Davis in the splendid biography William S. Hart: Projecting the American West. He was overwhelmed with “rancor, prejudice, and self-pity.”

One of Hart’s friends, Charles C. Cristadoro, was an inventor and sculptor. He’d been invited to help create Mount Rushmore, and later worked for Disney creating sculptures of Pinocchio, Geppetto, and other characters for puppeteers to use as models. Around 1925, Hart hired Cristadoro to cast a massive bronze statue, more than 6 feet in height. Hart paid $20,000 for it (more than $300,000 in 2022 dollars).

The statue had to be big, because Hart intended to install it at a big spot: the Grand Canyon. “In my eyes the Grand Canyon … is a religion symbolically taught,” Hart wrote. “The artist has caught a look of distance in the eyes that would match the location we seek,” he said elsewhere, “as though the work was modeled on that very spot where God made life in death.” The subject was Hart himself, on horseback. “I have an uncontrollable desire to have a reproduction of myself and my horse placed at some lonely spot on the rim of the Grand Canyon of Arizona, far away from crowds and the strife of life.”

The Grand Canyon had become a national park only six years prior. The National Park Service was engaged in an ongoing battle with a prospector-miner-developer who wanted to privatize the site and, in support of that quest, had gotten himself elected to the U.S. Senate. Amid this battle, nobody was going to donate a corner of the canyon for some other egotist to use as a monument to himself. Hart was left with a homeless statue.

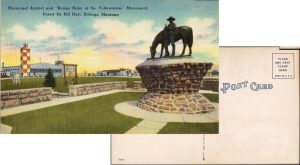

Courtesy Of Billings Logan International Airport; Photo By D. Schmitt

In June 1926, Hart traveled to Hardin, Montana for the 50th anniversary of Custer’s defeat at the Little Bighorn. The anniversary had been weirdly reconceived as an Old West celebration in which whites and Indigenous peoples alike could rejoice in nostalgia. Hart claimed to be a Custer expert with insider knowledge about the battle. He claimed that he spoke to Indigenous people there in their own language. He also met some friendly folks from the nearby city of Billings.

Billings sat in the valley of the mighty Yellowstone River, backed by the nearly impenetrable sandstone cliffs known as the Rims. If you squinted, you could think of it as a mini Grand Canyon. In the 1920s, the city’s downtown was extending toward the Rims: Ground had been broken for two hospitals and a college, along with an airport overlooking them.

For the Fourth of July, 1927, the city was planning a 45th birthday jubilee. It would include fireworks, Crow dances, a poetry reading, and an appearance by the “last of the living overland stage drivers.” Leaders knew just the honored guest to invite.

Hart, Cristadoro, the horse Fritz, and friend Bert Rollins were feted all weekend. Introducing Hart, a judge said that he had “put into the West the most heroic deeds of any living man.” A reporter gushed that Hart “had a smile for everyone, which quite dispelled the idea that the grim cast of countenance as depicted on the screen was his usual demeanor.” In prepared remarks, Hart spoke of the West as “the land of staunch comradeship, of kindly sympathy, of kindred intellect, where hearts beat high and hands grip firm, where poverty is no disgrace and where charity never grows cold.”

If the sentiment was a bit mawkish, it was far from egotistical. Away from Hollywood, out in cattle country, Hart was able to rediscover his inner moral strength. He could now say that the statue wasn’t about him. Hart not only donated the statue to the city — he also allowed it to be titled Range Rider of the Yellowstone, rather than something like Bill Hart, Cowboy Hero. Though he’d posed for it, he now said he was merely standing in for all the cattlemen of the West. The spotlight shouldn’t be on Hart himself, he implied in Billings, but on the everyday people who loved the same nostalgic, authentic spirit of the West that he did.

For the Fourth of July, 1927, Hart donated to the city of Billings Charles Cristadoro’s massive sculpture Range Rider of the Yellow- stone. The sculpture (opposite, and on an old postcard to the right) still stands near the airport.

It wasn’t a complete transformation: After Hart returned to Hollywood, he too often became enmeshed in his petty hatreds. But, when he died in 1946, he showed the world this redemptive streak he’d nurtured in Billings. He willed his ranch to Los Angeles County for use as a free-to-the-public park. “While I was making pictures,” he wrote, “the people gave me their nickels, dimes, and quarters. When I am gone, I want them to have my home.”

Hart termed the Yellowstone Valley “the smile of the West.” In a park adjacent to the airport and the Yellowstone County Museum, the Range Rider of the Yellowstone still surveys a growing city and vast cattle ranches. A plaque identifies the figure’s model as William S. Hart. But it’s a monument to authenticity, rather than Hart’s ego. As a journalist wrote at the unveiling, the noble horseman has a “life-like attitude as if looking out on the great valley below.”

A regular contributor to Big Sky Journal, John Clayton is the author of Wonderlandscape: Yellowstone National Park and the Evolution of an American Cultural Icon and Natural Rivals: John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and the Creation of America’s Public Lands.

No Comments