28 Sep History: Glimpses of Glacier

Tucked away in the Glacier National Park photo archives, under the careful stewardship of the National Park Service, are hundreds of photo negatives and prints by Tomer J. Hileman, one of the park’s most prolific photographers from nearly a century ago. And just as the glaciers hide secrets under ancient sheets of ice, these photographs preserve a time in history when visitors were just beginning to glimpse the wonders of glaciology in the northwest reaches of Montana.

Hileman was born in Marienville, Pennsylvania, in 1882. After moving to Chicago for work, he attended the Effingham School of Photography there before venturing to Colorado, where he documented the booming industrialization of ore extraction in the Cripple Creek District. But drawn to more natural wilderness settings to practice his photography, he discovered Montana’s Flathead Valley in 1911, just a year after Glacier was established as a national park. Two years later, he married Alice Esther Georgeson in what was allegedly the first wedding in the park, although the exact location of the event is unknown.

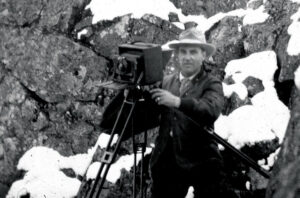

Hileman readies his camera while shooting on the Continental Divide by Fifty Mountain. Hileman, helped to document the receding glaciers that are studied today.

Together, the couple established a small photo studio in Kalispell and a summer outlet in nearby Whitefish, adjacent to the Great Northern Railway’s transcontinental rail line. After meeting station masters and passenger agents, Hileman began taking promotional photographs of the park for the railroad. He started with images of the hotels and chalets that the Great Northern had begun building in Glacier, aiming to lure passengers to the “Alps of America.”

As a result, Hileman was appointed the official Great Northern photographer for the Glacier Park District in 1924. He was paid a salary that was “not to exceed $25 per week,” along with free transportation, room, and board. Hileman retained the copyrights to all of his negatives and sold the prints to the railroad for 35 cents apiece. And it wasn’t long before his photographs adorned placemats, brochures, wall murals, calendars, postcards, playing cards, and posters, among other things.

Edwards Mountain hovers in the background, as guests enjoy the sun-soaked porch of Sperry Chalet, which was built in 1913, photo by Tomer J. Hileman.

In the early 20th century, all of the big railroad companies capitalized on natural attractions that were adjacent to their rail lines: The Canadian Pacific had Jasper and Banff national parks, the Northern Pacific had Yellowstone, the Central Pacific had Grand Canyon, and the Great Northern — eager to grab equal markets — had Glacier. To get the word out, they needed professional photographers like Hileman who could translate the scenery into an alluring visual format. Other photographers also helped, including Fred Kiser and R.E. “Ted” Marble, who was employed periodically to supply photos to the railroad’s advertising department in St. Paul, Minnesota. But Hileman, a year-round resident with a thriving photo studio and an eagerness to take on more contracts, was the most dependable.

Since many of the Glacier tourists at the time were wealthy travelers from the East Coast, it made sense for the Great Northern to capitalize on Hileman’s dramatic and mystical photos of the Northern Rocky Mountains. And professional-grade black and white photographs were required for corporate advertising.

From The Loop on the Going-to-the-Sun Road in Glacier National Park, Hileman photographed Heavens Peak in the Livingston Range.

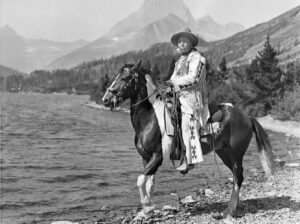

The Great Northern advertising department also knew that East Coast audiences were fascinated with Native American culture. Accordingly, they directed Hileman to take both group and individual photos of Blackfeet tribal members, titling them as “Glacier Park Indians,” even though they were traditional dwellers of the Northern Plains, not the mountains in that area. But more concerned with market share, the railroad was determined to put that cultural niche to work for them, no matter how flawed. This resulted in hundreds of portraits of Blackfeet adorned in traditional regalia.

Always on the hunt for promising business opportunities, Hileman made an arrangement with Great Northern officials to process film for tourists at photo labs in Many Glacier Hotel and Glacier Park Lodge. It was altogether symbiotic, as each hotel would provide the space and Hileman would charge guests for the services, allowing travelers to return home with dramatic pictures of Glacier National Park in hand to show friends and family. Hileman made money, and the railroad secured a secondary advertising outlet.

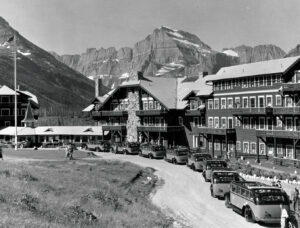

Automobiles and buses line up in front of Many Glacier Hotel, photo by Tomer J. Hileman.

The nature of Hileman’s work in Glacier was strenuous and eventually took a toll on the photographer’s health. To secure panoramic shots and capture views of the glaciers in the cirques below, he had to climb many of the park’s rugged peaks while hauling bulky Eastman Kodak full-frame cameras, filters, and plates. Often, Hileman used his connections with local homesteaders, packers, and their horses to haul his equipment to remote sites, allowing him to capture rare photographs. One example is an image of a mountain goat with its foot raised slightly and grass hanging from its mouth, and another features a chalet basked in the late evening sunset, with one side lit up and the other darkened in shadows.

Many of Hileman’s works in the park’s photo archives are documentary-like, recording buildings and human activity in mundane settings. Another popular genre was the postcard, featuring photographs that were less dramatic than the more carefully composed landscapes and Blackfeet portraits that he took deep pride in.

A canoe cruises through Glacier’s Red Eagle Lake, with Mount Logan and Logan Glacier in the distance, photo by Tomer J. Hileman.

A consummate businessman, Hileman sought his own element of artistic delivery, and the park gave him the perfect tableau. He made a comfortable career with his photographs, yet unknowingly provided another important record: his images of the ice-filled tarns and cirques preserved evidence of glacial retreats that would be uncovered 100 years later by climatologists seeking to understand our warming planet.

The Great Northern’s boom years in the park continued through the ‘20s, but declined during the Depression and World War II. Along the way, Hileman and the railroad nurtured their shared business ventures until, at his wife’s urging and with concerns over his health, the couple eased away from their Glacier businesses. It’s not altogether clear when his association with the railroad ended completely, but he signed his last formal contract with them in 1937.

A snowy bank gives way to the grandeur of Mount Cannon, reflected in the glassy waters of Lake McDonald, photo by Tomer J. Hileman.

However, the Hilemans pressed on with their studio in Kalispell, expanding it to include portrait shoots, film developing, image enhancements, and framing. Many of Hileman’s later photos of Glacier included colorized pictures and tinted lithographs, an emerging and popular medium.

It would be a stretch to place Hileman in the lofty circles of Edward Curtis or William Henry Jackson. Yet his careful compositions, coupled with a determination to reach remote locations for that just-right image of Glacier’s tortured landscapes, should land him in their company and rightfully parallel their achievements in many ways.

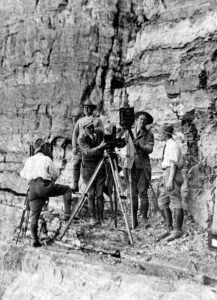

Hileman helped to create a publicity film for the Great Northern Railway on the north side of the Ptarmigan Tunnel in 1932. From left to right: Hileman, O. J. McGinnis, Howard Cress, George Grant, and George Ruhle.

Today, Hileman’s few original framed, signed, and hand-tinted photographs that are still in circulation command handsome prices at auctions and galleries. In 1985, the Glacier Natural History Association purchased more than 1,000 of his nitrate negatives to augment their collection of his works, which already contained more than 2,000 prints. The Glenbow Museum in Alberta, Canada, also displays more than 100 of his original prints with a focus on Blackfoot history.

John Two Guns White Calf, pictured here with his favorite horse, was a Piegan Blackfeet chief who was revered for his work promoting Glacier National Park and the Great Northern Railway.

In his later years, Hileman spent much of his time with his wife Esther at their home on Flathead Lake, up until 1945 when he died at age 63. Esther married again, outlived her second husband — a Kalispell school principal — and died at age 96 in Bigfork, Montana. And although she and her photographer husband had no children, Hileman’s most durable legacy lives on, tucked away in Glacier National Park’s photo archives.

No Comments