31 Jul History: Charlie Russell Versus the Automobile

On a visit last spring to the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls, Montana, I was surprised by two insights. First, Russell’s visual storytelling is astounding. Second, some of those stories involved automobiles.

The first insight shouldn’t have been a surprise. “Russell was a wonderful storyteller,” says Sarah Adcock, associate curator at the museum. “His work captures scenes either right before or at a story’s climax — so he lets the viewer finish the story.”

Russell [1864–1926] arrived in Montana in 1880 as a 16-year-old sheepherder. He cowboyed for more than a decade before getting married, moving to Great Falls, and discovering that he could make a living as an artist. Over the course of his career, he created more than 2,000 paintings, as well as sculptures, illustrations, and books. One of his paintings hangs in the House Chamber of the Montana Capitol building, and a thousand more populate the Great Falls museum, which includes his old log-cabin studio.

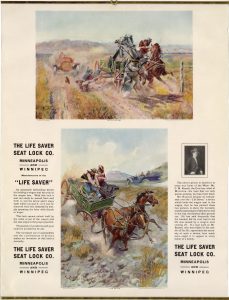

The Life Saver Seat Lock Co. reproduced two of Charles M. Russell’s 1910 watercolors, An Old Story and The Life Saver, in an ad with a testimonial from Russell. | UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY DIGITAL COLLECTIONS

Russell painted Western cowboys, Native Americans, and landscapes. “He had a nostalgia for things that had passed,” says John Taliaferro, author of Charles M. Russell: The Life and Legend of America’s Cowboy Artist. “He captured more ideal times — which, in truth, had come before he showed up.”

Russell’s art, Taliaferro tells me, often shows meetings of people: cowboys on a roundup, Native Americans encountering explorers, or friends stopping by the house at Christmastime. It’s people who populate the most vibrant stories.

As a storyteller, Taliaferro says, Russell had an audience in mind: his friends at the Mint Saloon on Central Avenue in Great Falls. Many were old cowboys, skeptical about progress in the same way that older people today are skeptical about AI. So Russell, perhaps adopting something of a persona, enjoyed telling stories that complained about newfangled contraptions or ways of making a living that didn’t involve herding cattle from horseback.

Author Raphael Cristy, in his book Charles M. Russell: The Storyteller’s Art, notes that Russell never painted mining, smelting, sheep ranching, wheat farming, or logging. Cristy quotes Russell, while he vacationed in California in 1920, as writing to a friend that he never painted “fruit, flowers, automobiles, or flying machines.”

That last claim was an exaggeration. It’s true that automobiles — along with railroads, barbed wire, and the automatic rifle (“a God-damned diarrhoea gun,” in Russell’s words and spelling) — represented the so-called progress that Russell stood against. But that made for good conflict.

This is evident in Russell’s 1907 watercolor, White Man’s Skunk Wagon No Good Heap Lame, which shows an Indigenous family on horseback encountering a broken-down Ford that’s also stuck in a mudhole. Russell, with his sympathy for Indigenous perspectives and love of verbal playfulness, referred to the car using the Blackfeet-coined “skunk wagon,” which references the vile smell of gasoline.

In 1910, Russell depicted a more intense car conflict. In An Old Story, horses have been spooked by an automobile and are dragging a wagon off the road. A female passenger is thrown into a barbed-wire fence. The male driver, still holding onto the reins, is tossed into the path of the oncoming car.

“It vividly captures that moment,” Adcock tells me. “The horses have so much movement and action. You can feel the adrenaline.” Russell had a genius for composition, color, and striking detail. The man’s hat, bouncing off his head, is a foreground focus. Behind it, you see the car is covered in dust. The wagon seat, a long piece of wood, has clearly come undone.

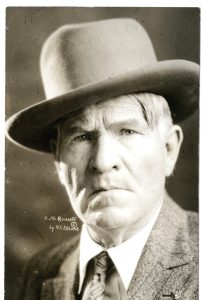

Russell (shown here in a late-life portrait by Great Falls photographer H.C. Eklund) could personally vouch for the wisdom of locking the seat to the wagon. | ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, MANSFIELD LIBRARY, UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA

The title referred to how common it was for spooked horses to cause injuries. But the flying wagon seat was the key to the whole scene. Russell often said that the hardest fall he himself ever took was caused by a wagon seat coming off. Familiar with the experience, he was readily eager to create the painting for a friend: Victor Heydlauff.

Heydlauff, a former Michigan school teacher seeking a drier climate, arrived in the Great Falls area in 1898. He worked as a cowboy and may have met Russell at the Mint. Later, Heydlauff bought land on Sage Creek, at the Montana-Alberta-Saskatchewan border. In his first winter, he didn’t have time to finish building a log cabin, so he set up a tent inside it and used the snow that accumulated between the cabin and the tent to keep him warm.

Heydlauff had a fertile, creative mind. He developed a hard strain of alfalfa suited to the harsh climate. He spent 10 years building a 20-foot-high dam to create a 500-acre reservoir that both irrigated his crops and provided a sanctuary for thousands of ducks and geese. He wrote cowboy poetry. After watching a woman leap from a burning building in Havre, Montana, he designed and patented a belted fire escape. And in 1910, after a dangerous fall of his own, he invented a device that locked a wagon seat to the wagon box, to prevent passengers from being thrown.

On August 5, 1910, Heydlauff spent several hours visiting Great Falls, where he told a newspaper reporter that the nearest city to his ranch, Medicine Hat, was “said to be the coldest place on the North American continent.” He also reconnected with Russell and his wife, Nancy. A brilliant businesswoman, Nancy was managing her husband’s career in ways that were gaining him fame. Heydlauff asked if Russell might make two paintings as an endorsement that Heydlauff could use for promotion.

This was an easy job for Russell. “He could work out of his head,” Taliaferro says, meaning that Russell could visualize a scene without having to do much research. “He had bigger projects, but he was easily distracted and loved doing whimsical things for friends.”

Russell’s funeral in October 1926 was a Great Falls holiday. Although cars lined the streets, Russell himself asked for a more old-fashioned conveyance. | MONTANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY RESEARCH CENTER

Indeed, that’s how Russell’s career had started. As a night wrangler, he made art to give away to friends. He was surprised when he was able to sell art, and even more surprised when Nancy’s work eventually made him the highest-paid artist of his time.

For Heydlauff — and in the C.M. Russell Museum today — An Old Story is the beginning of a story that finishes with The Life Saver, a similarly sized watercolor. “The car is farther away, but you can still see how it has scared the horses,” Adcock tells me. The situation is almost more precarious, with the wagon heading into a ditch. But the seat is locked in place. The passengers are safe.

“Russell’s oils have gotten recognition because they’re so large and catch the light so well,” Adcock says. “But his watercolor technique was unrivaled.” Because oils take so long to dry, the artist can change, mix, and edit. But with watercolor, “You need to let go of control,” she says. “You need to let the paints do what they want.” For Russell to capture his fine, telling details in this more difficult medium was an extraordinary accomplishment.

Heydlauff took the paintings to Brown & Bigelow, a print shop in St. Paul, Minnesota that specialized in reproducing paintings. (It would later publish millions of Norman Rockwell calendars.) Its color poster paired the two paintings and added some text describing the contraption. “If a man such as Mr. Russell, who has ridden in the saddle all his life, appreciates the necessity of such a device, how much more ought it to appeal to every father of a family,” the text read.

An accompanying black-and-white brochure claimed that Russell himself had named the device. “This is the automobile age,” it said, “and there is scarcely a country horse that is not frightened by automobiles, especially when in the hands of careless drivers.”

Copies of the poster are now in the archives of the University of Calgary and the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma. It’s beautiful. But at the time, it made for poor marketing. There’s no evidence that it was well distributed or ever published in a magazine or newspaper. The Life Saver Seat Lock Company seems to have met with little success. Heydlauff later reported that one year, when he was broke because his wheat crop failed (probably in the late 1920s), he sold the two paintings to a Great Falls collector for $1,000 apiece.

In his later years, Russell increasingly turned his storytelling gifts to the written word. His essays and short stories cover tensions in the 20th-century West, including automobiles. For example, one story has an old cowboy named Pat driving a car past “what looks like Stanford as far as he could tell at the 80-mile gait they’re goin’,” whereupon his passenger asks what’s the hurry. “‘I’m in no hurry,’ Pat yelled, ‘but I’m damned if I know how to stop the thing. We’ll have to let it run down.’”

Russell and his wife, Nancy, are pictured here in 1908. Even as Nancy’s management was making him the nation’s highest-paid artist, Russell took a whimsical break to paint the two threat-of-autos watercolors for his friend Victor Heydlauff. | MONTANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY RESEARCH CENTER

As for autos in Russell’s own life, “‘I wouldn’t drive one of them pesky cars fer love er money,’” Cristy quotes him saying. “‘My favorite’s still the hoss. But jest the same, I let Nancy have her automobile, while she lets me have two hosses. It’s a 50–50 game with us.’”

When Russell died in October of 1926, his funeral made for a Great Falls holiday. Schools, banks, and the post office were closed. For the procession from his memorial service to the cemetery, thousands of people lined the streets. Russell’s body was carried not in a skunk wagon, but in a horse-drawn hearse with a saddled, riderless horse tied behind.

Nancy had found the hearse stored in a nearby town. It hadn’t been used in 15 years, but this had been Russell’s wish and his way of honoring the old times.

As I left the museum on my visit last year, I was able to pay my respects. The hearse is now on display — an artifact from one of Russell’s greatest stories, his final victory over the automobile.

A regular contributor to Big Sky Journal, John Clayton is the author of several books, including Wonderlandscape, The Cowboy Girl, Stories from Montana’s Enduring Frontier, and Natural Rivals. He also writes the weekly email newsletter “Natural Stories”; johnclaytonbooks.com.

No Comments