22 Nov HISTORY: CHARLEY PRIDE’S MONTANA

Country music legend Charley Pride traveled some of the most significant miles on his pioneering path to the top of his profession while in Montana. He came to Big Sky Country in 1960 as a minor league baseball player, pursuing his lifelong dream to play in the major leagues. As an African American, he encountered few people who looked like him in the overwhelmingly white state, yet he quickly gained acceptance from those who watched him perform. He excelled on the baseball diamond while pursuing his other vocation after hours: singing and performing music. A large local audience responded to his talents in both disciplines. Pride made Montana the home where he and his wife, Rozene, raised their young family — first in Helena and then in Great Falls. Eventually, he signed a recording contract and became one of country music’s top stars. In the early 1970s, the Prides left Montana, but the family still regards the state as one of their homes.

Pride embraced the Treasure State and its people for the rest of his life. His son still looks back fondly on his childhood there. “My time in Montana was one of the best times in my life,” says Dion Pride, Charley’s youngest son. Dion is now an accomplished musician in his own right, having first played guitar in his father’s band and now performing worldwide as a touring solo artist. “The places where I grew up and the people I grew up with were nothing short of paradise to me. I’ve never seen a more beautiful place on this earth than my home state of Montana.”

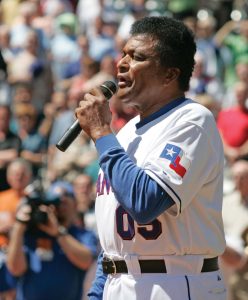

Charley Pride took batting practice during the Texas Rangers spring training in the 2010s. Decades earlier, Pride played in a spring training game for the Rangers and got a hit off future Baseball Hall of Famer Jim Palmer. | COURTESY OF TEXAS RANGERS

The Charley Pride that Montanans embraced became one of the most significant performers in the history of popular music. Before Pride, the only major African American star in country music history was DeFord Bailey of the Grand Ole Opry. Pride earned an unprecedented level of success and acclaim for an African American in a genre of music that had been performed primarily by white artists. Twice honored as Male Vocalist of the Year by the Country Music Association, he recorded 29 number-one singles on the Billboard country charts. Pride’s songs, such as “Kiss an Angel Good Mornin’,” “Is Anybody Going to San Antone,” and “All I Have to Offer You (is Me),” are now standards of the genre. He is a member of the Country Music Hall of Fame and the Grand Ole Opry.

Later in life, Pride became part owner of the Texas Rangers and often sang the national anthem before games, just as he had decades earlier in Montana. | COURTESY OF TEXAS RANGERS

Beyond his talent on stage, he was well known for his kindness and sincerity. “He was just a wonderful person. I’ve never met more of a gentleman,” says Monty Cowels, who served as Pride’s drummer in the Night Hawks, his band in Helena in the mid-1960s. At the time, Cowels was in her early teens, herself a pioneering performer in the region’s country music scene. She remembers a couple of occasions when people yelled “nasty names” at him, but those were infrequent occurrences. Pride learned to be a gentleman in the face of animosity as a child in Mississippi.

Charl Frank Pride was born on March 18, 1934, in Sledge, Mississippi. His parents were sharecroppers in the Mississippi Delta, and he was one of 11 children. St. Philip’s Missionary Baptist Church in Sledge served as a haven in an often heartless world for Mack and Tessie Pride’s large family, as did baseball and music. “Charley,” as he came to be known, and his older brother, Mack, both played professional baseball.

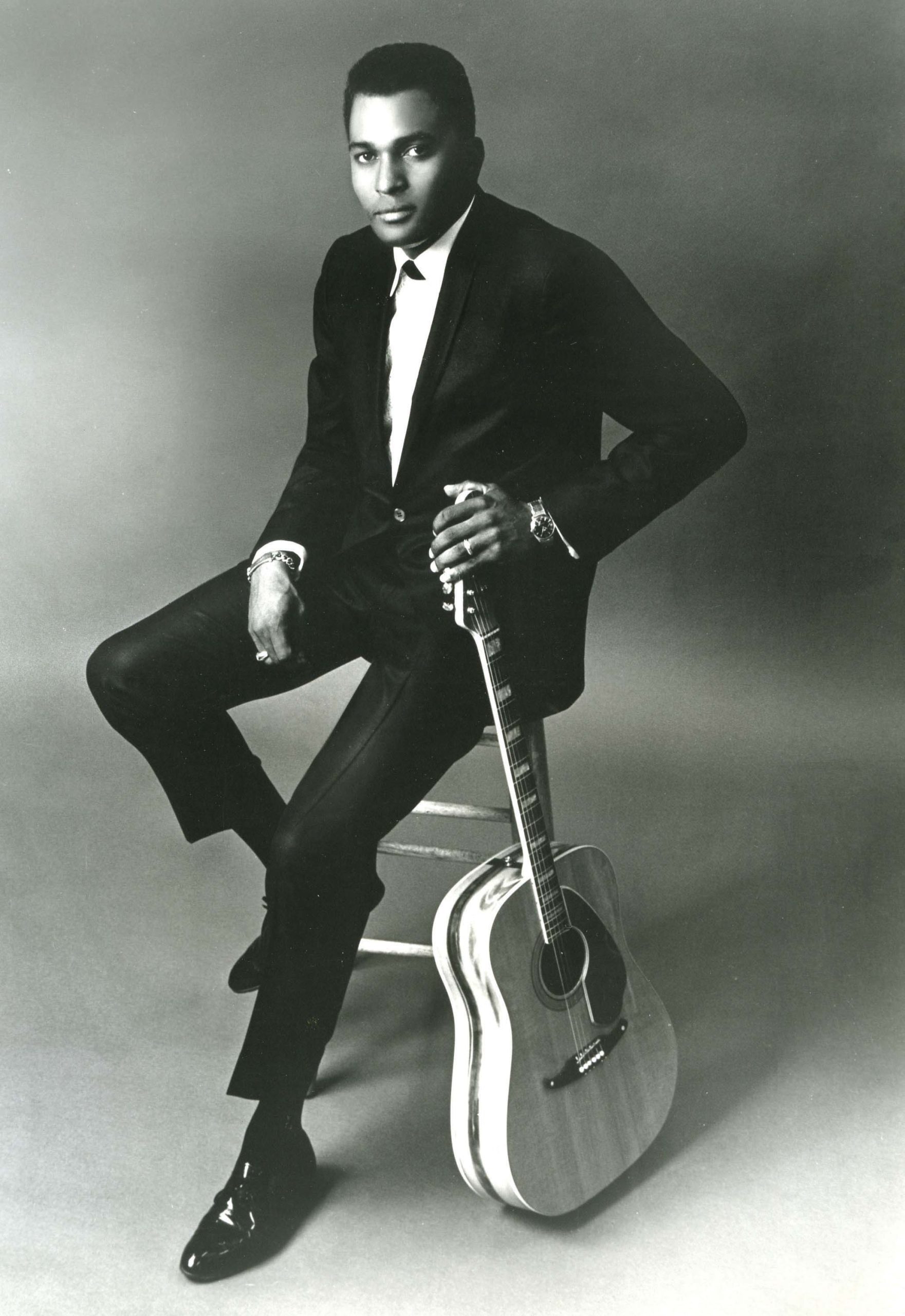

Pride took great interest in country music, listening to WSM radio in Nashville every Saturday night for the Grand Ole Opry. At age 14, he saved enough money to buy a guitar from the Sears & Roebuck catalog and started learning songs of the day.

Pride’s pursuit of both baseball and music took him far from Mississippi. His baseball odyssey meant travels all over the country during the 1950s, as he traversed both the segregated and minor leagues. Pride was a pitcher who could also play in the field and hit for a high average. He did several stints for the Memphis Red Sox of the Negro American League, pitched for New York Yankees affiliates in Idaho and Wisconsin, and played for a time in independent leagues in the Southwest. All the while, Pride passed the time by serenading his teammates and plucking his guitar on the daylong bus rides that constituted life in the minors. During his travels, he met Rozene Cohran in Georgia, who later became his wife.

The soon-to-be-married Pride received his draft notice in 1958 and reported to basic training for the U.S. Army in Arkansas. During his time in the Armed Forces, he married Rozene, and they welcomed the birth of a baby boy named Kraig.

After 14 months in the Army, Pride received his discharge and pursued his baseball career once again. He answered an advertisement in the Sporting News from the Missoula Timberjacks, the minor league baseball affiliate of the Cincinnati Reds in the Class C Pioneer League. The Timberjacks’ management told him to get in shape and head to Montana. So, Pride mortgaged his furniture and headed to Missoula for another shot at professional baseball.

He played only briefly with Missoula, making three appearances on the mound before his release. He then went to East Helena to play for the city’s semi-pro baseball team, the Smelterites, in the independent Montana State League. To play for the Smelterites, team members had to work at the zinc smelting mine for the American Smelting and Refining Company. Pride’s job at the smelter consisted of loading coal into a furnace. It was hot, dirty, and heavy work, but Pride earned a good wage: $100 a week. That wasn’t counting the $10 he earned each game playing baseball. Once Smelterites Manager Kes Rigler learned of Pride’s musical ability, the rising star began earning an extra $10 a game to perform a few songs before the first pitch or sing the national anthem.

In 1960, Pride batted over .400 and helped lead the Smelterites to the Montana State League championship. His on-field performance for East Helena earned him brief tryouts with two major league teams: the Los Angeles Angels and the New York Mets.

All of these revenue streams helped Pride achieve one of his major goals: buying a home for his family. Pride purchased an 800-square-foot home on Peosta Avenue in Helena, not far from Carroll College, and moved his wife and son, Kraig, up from Memphis. Dion and the couple’s daughter, Angela, were both born in Montana.

During those early years in Montana, Pride played as a solo artist at venues like the Corner Bar and Main Tavern in East Helena. Initially, advertisements for his performances purposefully excluded a picture. However, Pride was often quoted as saying that once audiences in Montana heard him sing, they didn’t care about the color of his skin. In 1963, he started performing with a new band, the Night Hawks, focusing largely on music after an offseason ankle injury brought his baseball campaign to an end before it began. The band became regulars at the U & I Club in East Helena and the Silver Spur in Helena. The Night Hawks won over audiences quickly in some rough-and-tumble places. The patrons of these shot-and-a-beer saloons often showed up with gun holsters on their hips.

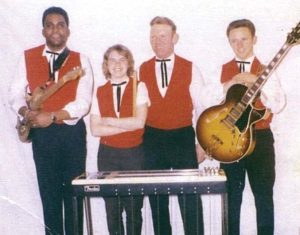

The Night Hawks regularly played two sets and performed for upward of four hours. “He was like a show on his own,” Cowels says. “By the second set, he’d come out, and the crowd would go nuts.” Cowels started drumming at age 10, and by the time she was 14, she’d earned a reputation as a drummer in the area. Cowels played 78 gigs with Pride, George Owens, and Jimmy Owens as the Night Hawks, primarily at the Silver Spur and U & I Club in 1964 and 1965.

Besides the occasional insults Pride endured, Cowels says the most evident example of racism she observed came when he was discounted as a suitable adult chaperone. To perform in bars, she needed an adult to accompany her, but Pride wasn’t allowed to serve in this role since he was a black man. Instead, one of the other bandmates was her chaperone at the shows.

Pride encountered the evils of segregation back in Mississippi and regarded his experiences in Montana as far different. In 2014, he told the Missoulian that people in Montana largely accepted his family and eventually embraced them.

“I faced no racism whatsoever as a little kid in Montana,” Dion says. “If I couldn’t have looked at myself or had a mirror, I wouldn’t have known the pigmentation of my skin in Montana. It didn’t matter.” Dion adds that during his family’s time in Great Falls in the 1960s and ’70s, he encountered great ethnic diversity.

Dion describes his parents as “very private” people, a sensibility that jibed with the down-to-earth character of many Montanans. Even as Pride became locally famous, people didn’t hassle him or his family when they were about town.

Dion calls Al Donohue, owner of the Great Falls-based country-music station KMON, “the closest to an entertainment person they encountered.” Donohue became a booster of Pride’s work and helped him get his first break in December of 1962, when country star Red Sovine was set to perform with Webb Pierce in Helena. Donohue got Pride a spot as an opening act. Sovine marveled at Pride’s smooth baritone voice and put the young singer in touch with some of his contacts in Nashville. This endorsement put Pride on the radar of top country labels, but he struggled to secure a record deal, largely because of his race.

Sovine put Pride to work with producer Jack Clement, who proved a game changer. Clement and Pride worked together on a series of demos that helped the Montana-based singer secure a deal with RCA in Nashville after a meeting with label head Chet Atkins in late 1965. Donohue helped finance the demo of “Snakes Crawl at Night,” which became Pride’s breakout hit on RCA.

Pride’s Helena, Montana band, the Night Hawks, included (from left to right) Charley Pride, Marty Cowels, George Owens, and Jimmy Owens. | COURTESY OF MONTY COWELS

In 1967, Pride moved his family from Helena to Great Falls to be closer to a larger airport. He flew out to performances on the weekends and spent the week at home with his young family. “My parents definitely preferred Great Falls,” Dion says. “It was where we developed our deepest relationships and close friends.”

They lived in a large home just to the east of Malmstrom Air Force Base. Their backyard backed into Pinski Park. “When he was home, he was dad. In summer, we’d play baseball and basketball, and during the winter months, we’d do football and ride snowmobiles and build snow forts and ride toboggans,” Dion says. He remembers hours spent throwing the ball around with his father and learning to ride a bike. Pride began teaching Dion how to play the guitar at age 5.

In the early 1970s, the Prides relocated to Dallas, Texas, but remained deeply enamored with Montana. Pride made frequent appearances in Montana at fairs and theaters in the state’s largest communities. He remembered Montana as the place where his dreams of family and vocation both came true. To carry on this legacy, Dion performs regularly at the Music Ranch in Livingston.

The big-league dream that brought Pride to Montana in the first place finally came to fruition, too. In 2010, Pride became part owner of the Texas Rangers. He had been attending the Rangers spring training annually since 1974 and performed concerts for the team in their clubhouse. Pride proved he could hang with the big leaguers well into his 40s. Once, he even played in a spring training game and got a hit off Baltimore Orioles ace and future Hall of Famer Jim Palmer.

Pride purchased his first home in Montana, a modest, 800-square-foot residence on Peosta Avenue in Helena. | COURTESY OF WIKICOMMONS

Pride died at age 86 on December 12, 2020. He was mourned by country music fans around the world and is widely recognized as a pioneering force in the music business, paving the way for an increasingly diverse fraternity of country artists. A significant swath of Pride’s pioneering path wound through the state of Montana, whose people proved strikingly accepting of the groundbreaking performer.

Clayton Trutor teaches history at Norwich University in Vermont. He is the author of Loserville: How Professional Sports Remade Atlanta — and How Atlanta Remade Professional Sports (2022) and Boston Ball: Jim Calhoun, Rick Pitino, Gary Williams, and College Basketball’s Forgotten Cradle of Coaches (2023); @ClaytonTrutor.

No Comments