23 Jul Outside: Hard Angle

WHEN I FIRST MOVED TO MONTANA I thought that being a true resident of Big Sky Country meant spending winter in the wind and snow. Those who headed south to Arizona, Florida and Mexico, among other palm-tree laden places, I deemed to be soft and uncommitted. Now I just see them as smart.

Similarly, I used to see fly fishers in black and white — dedicated hard-cores who fished through all seasons, in all spates of weather, versus posers who only threw dry flies under a hot sun partially obscured by heralded summer hatches.

Here, too, my opinion changed although I still believe that the jetsetters and fair-weather anglers miss some of the best that Montana offers, and they do so when the pace of life and the speed of an angling day falls in line with where it ought to be. In other words, you may not be able to escape the cold during winter, but you often find deserted rivers, feeding fish, and a civilized style in which to work them — no enduring the summer shuffle where boat-launch lines stretch four or five deep and the “aggressives” charge down riverbanks to stake daily claims on the most productive pools.

Despite the upside, I can’t blame those who say anglers are crazy to cast a line during winter, no matter the advantages, because the sight of a person standing waist deep in water, with chunks of ice nipping at their waders, and wind-driven sleet turning their stocking hats white on one side, isn’t a common vision of paradise. In addition, many people think that fish hibernate or simply don’t eat during winter, which makes us, standing waist deep in water and brutal weather, appear as if headed on a straight path to Warm Springs, the state’s psychiatric hospital. The truth is, trout eat all winter because they have to. They are no different than you and I. Fasting between the end of the regular trout fishing season, November 30, and the official start of spring, March 20, would have the same affect on fish as it would with us, which is to say, it wouldn’t be pretty.

Another misconception is that trout must eat enormous flies. When people travel through Montana during summer they easily strike a correlation between the salmonflies splattered on their license plates and the river flowing by 50 yards away. Ah, trout food they say. During winter, however, our rivers don’t offer those oversized insects. Instead of 2-inch salmonfly imitations we anglers tie on quarter-inch, size-18 Brassies and blood midges. To the uneducated, fishing such patterns for trout resembles luring in a pesky mouse by placing a single sesame seed on the trigger of a trap. “You expect to catch a trout on that tiny thing?” the naysayers ask. When it comes down to it midges, those tiny red, cream, green and often black-bodied miniscule morsels, often represent a trout stream’s largest single biomass and fish wouldn’t survive without them. On rivers such as the Bighorn and Missouri, winter midge hatches border on unbelievable with millions of the tiny little creatures flying in the air and crawling over the bankside rocks any given day. Trout, accordingly, feed heavily on those bugs, mostly under the surface. However, anglers often find trout keying on adult midges, which equates to rising fish and dry-fly opportunity.

I got into winter fishing when I was in college and learned that some of the biggest browns on Rock Creek, near Missoula, could be yarded out in February and March. I found those fish in the mid-depth, mid-speed runs and pools, and they couldn’t say no to a size-14 Prince Nymph or a size-18 Brassie. By the time winter ended and true spring arrived the college semester was almost over and I had an appointment with the dean of the journalism school — he wanted to know why I’d dropped two classes and performed poorly in others. I told him it was a money issue but, having kept tabs on my weekly outdoor column in the university newspaper, he knew the truth.

The feeling I got while fishing Rock Creek that winter was like finding a killer hole-in-the-wall restaurant before the big-city newspapers let out the secret and wait times went from nonexistent to an hour-long overnight. Winter fishing, it seemed to me, was a top secret to be held close until the masses discovered the appeal. I wanted to get in on all the action before it spiraled into the rat race summer fishing has become.

Despite the advent of excellent cold-weather gear for winter fishing, and despite the population increases of outdoor types in Missoula and Bozeman, I didn’t have much to worry about; winter fishing remains the sport of a brave, demented few, and we’ll continue to be looked at, right or wrong, as a bunch of freaks who prefer cold water and trout over powdered white slopes and après ski drinks.

After college in Missoula and my thorough Rock Creek education I moved to Seattle, Wash., for a decent job. But I missed the fertile Montana trout streams. So, one time, I compromised and talked a friend, Torrey, into joining me on eastern Washington’s Yakima River, which is as close as you get to a Montana-style trout stream within the borders of the Evergreen State.

We drove over Snoqualmie Pass after work on a Friday night in February and traveled through the kind of dismal weather and road conditions Washington is known for — heavy, wet snow, falling in blinding, quarter-sized flakes. Half-cocked idiots from the city sped by in their Landcruisers and Explorers, bouncing around in the 2-foot-deep slushy ruts, feeling four-wheel-drive invincible, risking their lives to get where they were going five minutes earlier than they would have if they’d driven safely. We caught up with at least three of those rigs, all in the ditch with their flashers on, before we turned off the interstate and headed into Roslyn.

At that time the television show Northern Exposure was being filmed there and Torrey and I thought we might glimpse a star at the Brick, a noted watering hole. At the least, we’d shoot pool and grab bar food before heading out to find a campground and pitch tents. Like a lot of those nights in my 20s, time has whittled that evening into a short, still-photo slideshow in my mind. When I think about that night I see four women saying we couldn’t take the empty seats at their table; two cowboys arriving and one of them ripping Torrey’s ball cap off his head; Torrey, in lieu, ripping one of those cowboys’ hats off their head and placing it on mine; and then driving away from the Brick with Torrey hanging out the passenger window shouting expletives at a cowboy and his girlfriend, whom I kept just out of reach of my rear bumper.

We pulled off the road a few miles later and spent the night in my standard cab truck … with my black Labrador, Shadow. On occasion, to this day, when I ask Torrey for a favor he’ll cite that evening — when my legs stretched across the truck and Shadow burrowed into his space — as reason for me to take care of things on my own. That he’s now my insurance agent may haunt me.

After our night at the Brick, Torrey and I brewed a thermos of coffee and charged out to the river. In memory it was a half-hearted affair. We spent an hour gearing up, another 20 minutes in the cab of the pickup with the heater pegged, and then we waded into the Yakima and worked what looked to be a perfect winter run — the water dropped from a shallow riffle into a pool and then slowly worked into a medium-speed, 4-foot-deep drift, which is ideal water for trout, no matter the time of year. That subtle flow allows trout to conserve energy, provides enough oxygen for survival, and delivers a winter menu of midge larvae, blue-wing-olive nymphs, and annelids. Several minutes in Torrey hooked a large fish, but it turned out to be a whitefish and he pitched it back with an old-school Montana grimace.

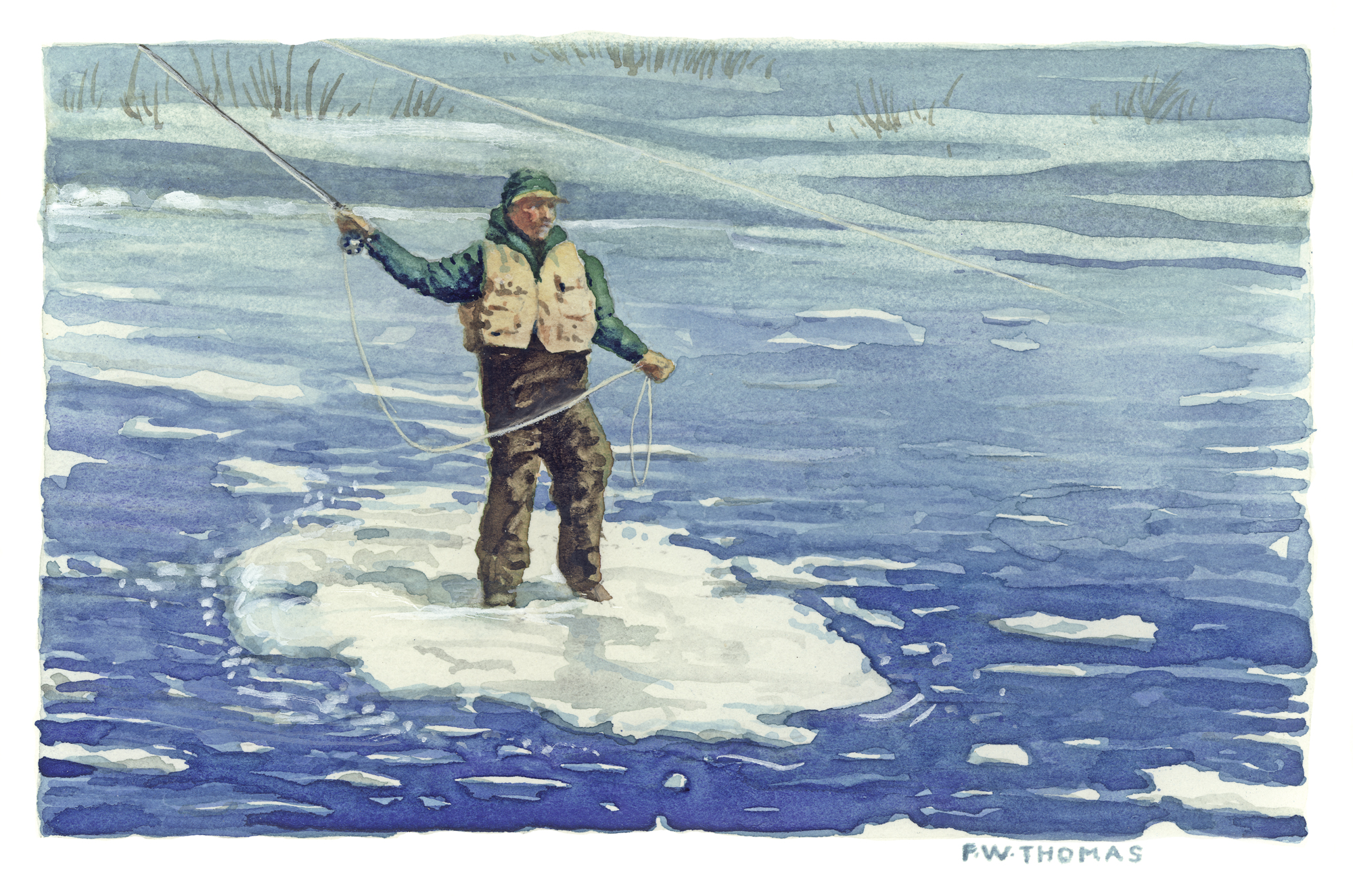

At noon my thermometer read 29 degrees and it was snowing. I was beginning to believe that I harbored a small leak in my waders. Ice coated the Yakima’s banks and travel up or downstream looked like it could be disastrous. But the willow-lined bank downstream held promise and Torrey wasn’t ready to accept my suggestion to head to Ellensburg to watch the Seahawks game. Instead, Torrey glanced upstream and then confidently stepped off the bank and onto a 3-inch-thick, plywood-sized sheet of ice and started casting toward the bank. As he drifted farther from the bank, over a deep pool and toward a fast run, he hooked some sort of fish; I saw his fly rod pulsing as he rounded a corner and I thought, momentarily, that I might not see him again … ever. I retreated to the truck, drove downstream along a road that mostly parallels the river and picked him up. He wore a big smile, said, “This winter fishing is pretty sweet,” and then showed me a soaking wet arm where he’d braced his fall.

I moved back to Montana, full time, in 2003. At that time I was single and just developing a magazine called Tight Lines — I had more than enough free time to spend on the water. That winter turned out to be one of the warmest on record and there were many days during January and February when the air temperature drove into the 50s and I fished the Madison River in a T-shirt. Other times it was the typical winter stew with temperatures hovering in the high 30s and low 40s with sleet or snow falling from the sky.

One day I decided to try the Madison’s channeled section near Ennis that closes at the end of February. Most anglers presume that stretch is closed during spring to protect spawning trout when, in reality, that restriction protects nesting birds that set up camp and raise young on the area’s numerous brushy islands. The area is also off-limits to fishing from boats. The requirement to wade a slick river when the air and water temperatures are dangerously cold keeps most people off the water from mid-October through the February 29 closure.

I can’t really blame people for their concern. As I walked down a trail on the Madison’s east bank it would have been easy to have slipped on the ice and fallen into the river. Depending on how far away from the parking lot that mistake occurred, anyone could have perished from hypothermia before getting back to a vehicle.

There are times when I question the appeal of winter fishing, especially when a north wind blows the Arctic into Montana, but then I’ll wander into a hole that is loaded with trout that haven’t seen a fly in weeks and it all makes sense again.

My go-to winter rig is a size-16 egg imitation trailed by a size-18 midge larvae, such as a Brassie. But the egg, really, is all you need.

That day I tied on one of my egg imitations, placed a couple BB-size split shot above those flies and affixed a strike indicator to the leader. I used to be opposed to strike indicators and I never fished them, at any time of the year, but my stance on those bobbers has lessoned over the years, mostly because I wonder why we should try to make a statement about cork when we’re all sinning beneath the surface with split shot and nymphs anyway. Unless we are true purists and married to the dry fly, we really don’t have room to complain. That would be like saying cars shouldn’t be built with headlights and that hunters shouldn’t use binoculars and scopes in pursuit of big game.

I hooked a good fish on my first cast into a prime hole, and then tagged a monster on my second. After a few good runs the fish arrived in the net and I placed a tape between the tip of its nose and the fork of its tail. Twenty-one inches. A rainbow. Back in 2003 it seemed like every winter fish weighed 3 or 4 pounds and you could land one giant after the other, which is what I did until late in the day when the temperature dropped and no amount of fish could have kept my mind off my frozen and now unresponsive fingers. With teeth chattering I waded away from the river feeling like I’d gotten away with robbery. Too good to be legal, I mused.

A couple days later, I took a friend to that pool and let him have his way with an egg pattern and those fish. When I look at pictures from that day I see a middle-aged man bundled up to the hilt trying to smile through half-frozen lips. His cheeks are burnt red and a stocking cap is pulled over the ears, as far down as he could get it, which didn’t seem nearly far enough. The man looks miserable, but to this day he calls that experience his best day ever.

I doubt winter fly fishing will ever be mainstream, but it’s nice to know there’s something to do during the cold months that’s at once entertaining and somewhat adventurous. You don’t have to taunt drunken cowboys and their girlfriends, you don’t have to ride icebergs down broad rivers, and you don’t even need to fish when the mercury drops below freezing and a fly rod’s guides ice up every third cast. Winter fly fishing is an adventurous excuse to see Montana during its roughest season and to marvel at the adaptive capability of trout. Like any decent endeavor, winter fishing provides stories, of misery and success, which carry us through the cold and the dark when the option isn’t Arizona or Argentina.

No Comments