30 Sep Flight of the Monarchs

THE SUN HAD JUST CLIMBED THE BITTERROOT MOUNTAINS and was piercing an overcast sky with pale rays one morning in late July when a pair of biologists fanned out in an Idaho field dotted with milkweed plants searching for monarch butterflies, among the most admired and mysterious of insects for an arduous mass migration that sees them winter in warmer climates.

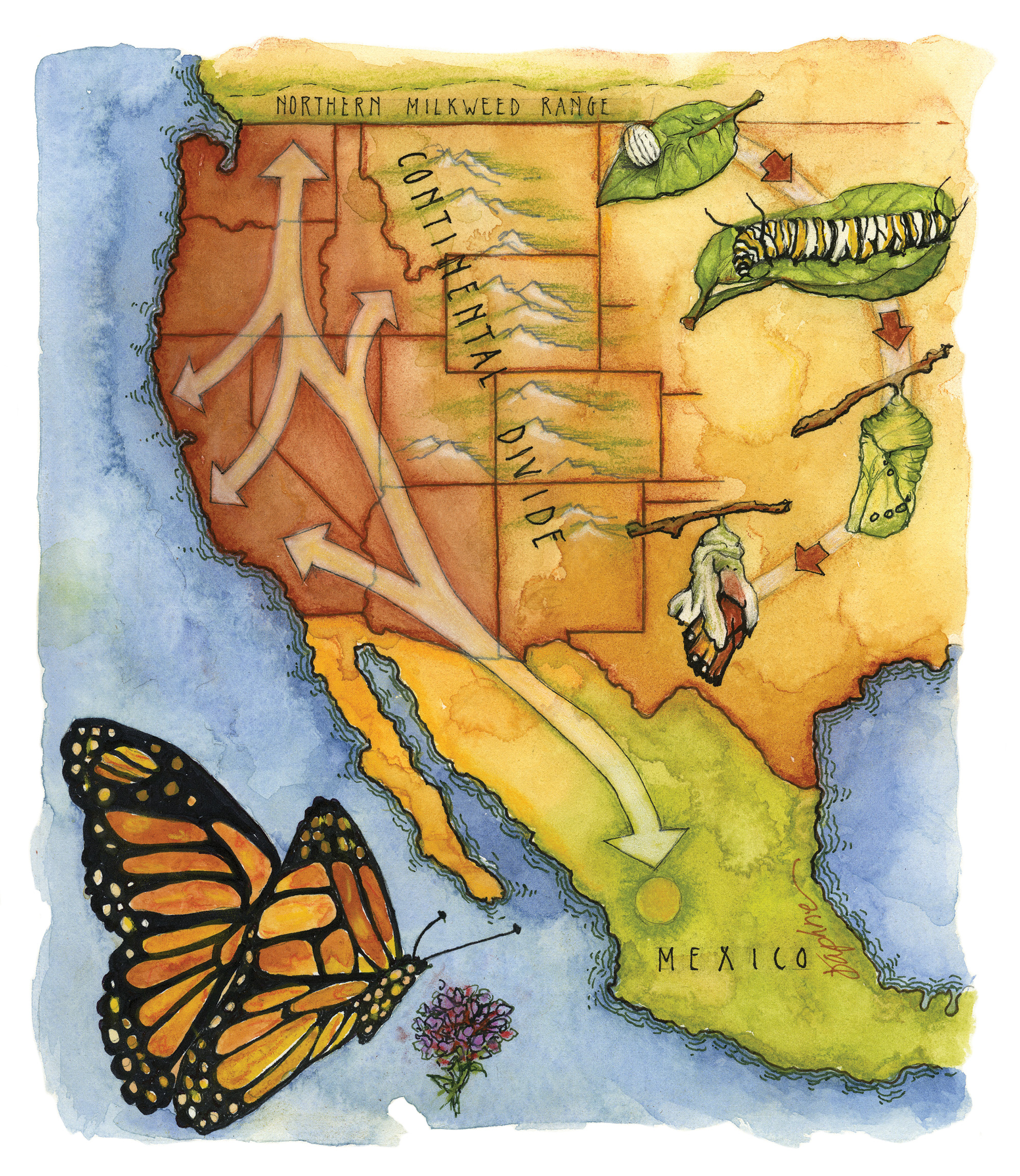

The orange-and-black butterflies are roughly divided into two populations in the United States, according to fall migrations that lead monarchs east of the Continental Divide to embark on a 3,000-mile journey to Mexico and monarchs west of the Divide to wing hundreds of miles to California from Rocky Mountain states like Idaho and Montana.

Monarchs are known for that migration (which is unique among butterflies for its regularity and extensiveness) for an ethereal beauty and for emerging from a jade green chrysalis adorned with gold stitching. Lately, they have drawn attention for population declines tied to such factors as destruction of the milkweed — misnamed native plants with orchid-like blossoms — that the butterflies depend on to lay eggs and provide food for hatching larvae. Plummeting numbers of monarchs have led some scientists to question if the singular seasonal migration will one day disappear.

Word of the insect’s plight led Beth Waterbury, regional wildlife biologist with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, to launch the first formal inventory of monarch habitat in the Salmon and Lemhi river valleys in the east central portion of the state.

This spring, Waterbury colleague, Toni Ruth, and a team of citizen scientists launched a months-long project to catalogue and monitor monarch milkweed sites clustered in the grasslands, foothills and waterways of a county which spans more square miles than the states of Delaware and Rhode Island combined.

Preliminary inventories have revealed patches of a type known as showy milkweed in pasturelands, along roadside ditches and on dry ridges in primarily undeveloped acreage outside the ranching community of Salmon. Waterbury said it was unclear why the butterflies appear to favor some milkweed spots and not others. And generation after generation of monarchs fly to familiar sites through mysterious mechanisms science has yet to fully explain.

“It’s a little bit of a miracle that they find these islands,” said Waterbury.

The project is expected to provide key information about the Northern Rockies portion of the western monarch population. Far less is known about the hundreds of thousands of monarchs in Western states than their eastern counterparts, which are better monitored by scientists, nonprofit groups and vast networks of enthusiasts, said monarch expert Karen Oberhauser, professor and director of graduate studies in conservation biology at the University of Minnesota and head of the school’s Monarch Lab.

“There are large gaps in information about the western migratory population since it isn’t as dense, people aren’t as familiar with it and the butterflies are not being studied in the same depth,” she said.

Monarchs on both sides of the Continental Divide suffer from the same troubling trend that has seen their numbers at wintering sites — the California coast and Mexico’s mountain forests — sharply fall. Data compiled by the Xerces Society, a nonprofit that works for the conservation of invertebrates and their habitats, shows just 1,300 monarchs clustered on a beach near Santa Cruz, California, in 2009 compared to an estimated 120,000 in 1997. And the number of butterflies that wintered in Mexico this year dropped to a level that a study by the World Wildlife Fund suggested was in the realm of a population crash.

The declines are strongly tied to habitat destruction. But Oberhauser said a host of factors are coming to bear on the delicate butterfly, including changes in agricultural practices that have brought a significant reduction in the number of U.S. acres taken out of production to allow for growth of vegetation like milkweed, spraying of stands with chemicals, climate changes, development and logging of trees where monarchs roost in a state of torpor in winter until the spring migration northward.

“It’s a little bit of a lot of things,” said Oberhauser.

The allure of the butterfly, once experienced, is lasting, casting a spell of wonder and delight among admirers and researchers alike. Recent canvassing of milkweed sites north of Salmon brought exclamations from Ruth, officially a wildlife technician for Idaho Fish and Game, who bent low to examine a gauzy chrysalis dotted with gold.

“It’s like nature’s jewel,” she said.

The chrysalis represents the last stage of a weeks-long metamorphosis that moves from egg to caterpillar of successively larger sizes to butterfly. One female will lay hundreds of eggs but just a fraction will become butterflies, said Ruth.

Oberhauser said insect predators and parasites are known to attack eggs and larvae, adding, “You never want to be a baby monarch; you have such a low chance of surviving.”

A toxin in the milkweed is taken up by monarch caterpillars and butterflies and lends them the so-called warning coloration that suggests to predators they are not just a pretty face.

“It tells birds that they should look elsewhere for a tasty tidbit,” Ruth said.

Monarchs that emerge as summer is winding into fall will not breed but rather conserve their energy and resources — gaining nectar from late bloomers like coneflower and asters — to embark on southern migrations that will see them fly during the day but not at night since they do not navigate by stars like birds, Oberhauser said.

The butterflies use the sun as a compass and use the Earth’s magnetic field as a magnetic compass on cloudy days, she said. Yet much is still unknown about monarchs’ homing instincts for their wintering grounds.

“We still don’t know how they find the exact same spot every year since very few, if any, make the round-trip migration,” said Oberhauser.

As monarch numbers decrease, researchers ponder the future of the long-distance journey.

“We don’t really know if there’s a limit or how small the population can get before the migratory phenomenon is no longer viable,” Oberhauser said.

For her part, Waterbury is clearing part of her garden to plant milkweed, with seeds and plants sold online. She, Ruth and volunteers are facing the prospect of limited to no funding if Idaho does not grant the monarch — the insect of Idaho and six other states — so-called species of greatest conservation need status.

Yet for Waterbury and Ruth, the weeks of seeking butterflies in 2014 will ever represent a season of enchantment, a period when untold forces of nature converged to give rise to the flight of the monarchs.

- Marks of the western monarch, from larvae to long distance migration from west of the Continental Divide down to Mexico.

- Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) on showy milkweed (Asclepias speciosa) in Salmon, Idaho.

- Idaho Fish & Game Wildlife Diversity Biologist Beth Waterbury (R) and Wildlife Technician Toni Ruth, Salmon, Idaho.

- This caterpillar is feeding on a milkweed seed pod. During this stage the monarch does all of its growing. As the caterpillar’s body grows larger it sheds its skin. There are five parts to this stage, which are known as Instars.

- The suspended pupa is jewel-like — jade in color with a crown of gold stitiching.

- As the shell bursts open and a monarch butterfly emerges, it takes several hours before it can fly because its wings are tiny, wet and wrinkly. The butterfly pumps body fluid, called hemolymph, into the wings to make them grow and harden for flight.

No Comments