03 Feb Fish Tales

Moby on the Madison by David Abrams

Lately, I’ve been thinking about my Moby — that bronze, freckled whale of a trout — on my daily commute along the busy interstate of the Madison River.

I first dreamt of my elusive monster fish in the late 1980s when my young family arrived in Ennis, Montana (population: slightly larger than a breadbox), from Oregon. I’d just graduated with a bachelor’s degree in creative writing, also known as “Good luck finding a job out there in the world, sucker!”

But I did find a job. In a type of miracle only Frank Capra could dream up, the valley’s weekly newspaper hired me as a reporter even though I had zero experience with journalism. The salary was low — slightly less than the average breadbox earned — but it was all I had (until a month later when I started moonlighting as a school janitor). I hoped the job would give me entrée into the town’s social circles — which, to this young immigrant from Oregon, felt as closed and hard as steel doors. I felt an awkward prickle of self-consciousness as someone who didn’t grow up in the valley, and couldn’t access those long-forged relationships that its residents shared. I was just this weird, shy refugee from academia. The only way it could have been worse would be if I had come from California.

I desperately, ridiculously wanted to be that Frank Capra character everyone greeted by name as he jogged down Main Street on a snowy evening, shouting, “Hi there, Valley Bank! Hello, you ol’ Madison Theater! Hey there, Long Branch Saloon — if you were a woman, I’d kiss you!”

But that wasn’t me. I was the silent one standing on the fringes of the glad-handing crowd after it spilled out of the Assembly of God church on Sunday morning.

Before too long, I got the notion in my head that a good reputation equated with a creel brimming with fish. Even in the ‘80s, Ennis was quickly becoming known as Trout Town, USA. Cutthroat behavior here was regarded as a good thing.

To be musked with fish brine would mean I’d truly arrived. Mind you, I was mostly an armchair angler — which meant if I had a choice I’d rather sit in an armchair reading about trout than actually be out there netting them.

But I overcame my self-doubt, and one day in October found myself on the banks of the Madison at a fishing access site just outside the town limits, squinting against the sun-sparkled riffles. Somewhere out there was The Big One I’d harpoon with a Royal Wulff. I’d hook a finger through its gills and march a one-man parade down Main Street. The fish would be my letter of introduction to what passed for high society in Ennis.

My Moby was not a particular trout, nor a singular dorsal cutting the current, not even a visible, trackable shadow, dark as a rock, beneath the surface of the Madison.

He was the idea of a fish.

He was the tug of line, the bend of rod, the orgasm-yelp of reel.

I had never seen my Moby. For all I knew he didn’t exist.

But he did exist. He was the need to be hullo’ed in the Ennis post office, to have the butcher at the grocery store start packaging my favorite cut of meat even as I walked to the counter, to feel the arms of acceptance hugging me close to the municipal bosom.

I stood on the banks of the river at dawn that day, scanning the hard water for this slippery notion of a fish. Above me, the sky lightened to the color of baby’s skin.

I wore the pair of old rubber chest waders my father had given me three years before. That slow small leak just below the left knee never really bothered me until this autumn day when I stepped into ice-cube water. I was 5 feet from shore when river water started seeping in. Soon, it felt like I was walking across a bed of cold nails.

I looked ridiculous, pathetic, anxious. I hoped no one saw me teetering off-balance at the edge of the Madison.

And yet I hoped they did, spreading the word around town that the “new guy” was “something of an angler.”

Behind me, cars passed along Highway 287 like little gusts of wind. Were some of them slowing down to watch?

I found my footing. I stripped some line. I raised my arm. I released a lasso of gossamer leader. I waited for my Moby to come to me. •

The Big One by Malcolm Brooks

In the summer of 1997 I found myself not quite finished with an English degree, engaged to be married, and just about as broke as I’d ever been in my life.

My fiancée and I wrangled an impossibly cheap rental two blocks east of downtown Missoula, in a rickety old working-class Victorian owned by a renegade former philosophy professor who, decades earlier, had run an ill-fated commune out of the place.

I was lamenting the loss of the 1960s myself, in a fashion. I’d totaled my prized ’69 Ford Bronco the winter before, ironically and maybe even prophetically while returning from a bridal shop in Hamilton. The wreck involved white snow, black ice and a death-dodging slalom 85 feet down a nearly vertical embankment, leading in large part to the aforementioned grim financial straits. By the time fishing season rolled around, the girl and I still had one car between the two of us. I could walk to work in 10 minutes, so she claimed the wheels most afternoons to get across town to her own job.

The Big One can obviously refer to any number of milestones or totems — weddings, wild trout, car wrecks. Even the previous winter fit the description, with the legendary Christmas Eve blizzard of ‘96 and an eventual total snowpack beyond what anyone but the old-timers could remember. The upshot relative to angling was that the rivers ran high and cold right through that long impoverished summer, the one year I had no consistent means of transport to Rock Creek or the Blackfoot or Bitterroot.

So I started fishing in town. I probably hit the Clark Fork a time or two, but mostly I’d walk straight up Spruce Street and over the railroad crossing, drop down into Greenough Park and start casting into Rattlesnake Creek.

Initially I didn’t expect much, to be honest. I knew the creek was a major player in bull trout restoration and that miles of it were permanently closed up in the wilderness area north of town, but I’d never heard of anyone fishing the legal lower stretch.

Still, the run through the groomed section of the park, once part of a Victorian estate, allowed me to fantasize about what it must be like to fish in the pastoral streams of England or France. Which was tantamount to fantasizing about not being broke and stuck.

Before long I quit fantasizing, because I started hooking fish. In short order I caught and released a handful of middling cutthroats and one 12-inch rainbow. No monsters, but no matter: I was catching freestone fish mere footsteps from the erstwhile commune. And at least as far as the angling went, I had the place totally to myself.

I wound up fishing the creek all summer, always in the evenings after work, when my betrothed was still across town with the car. I never did hook into a bull trout, but then I doubt I ever threw a streamer either. I did catch cutts and ‘bows by the score, some of them pretty decent, and a single, absolutely electric 12-inch brookie that caught me, as in totally by surprise. But the best fish of that season — The Big One — I caught, and caught, and caught again.

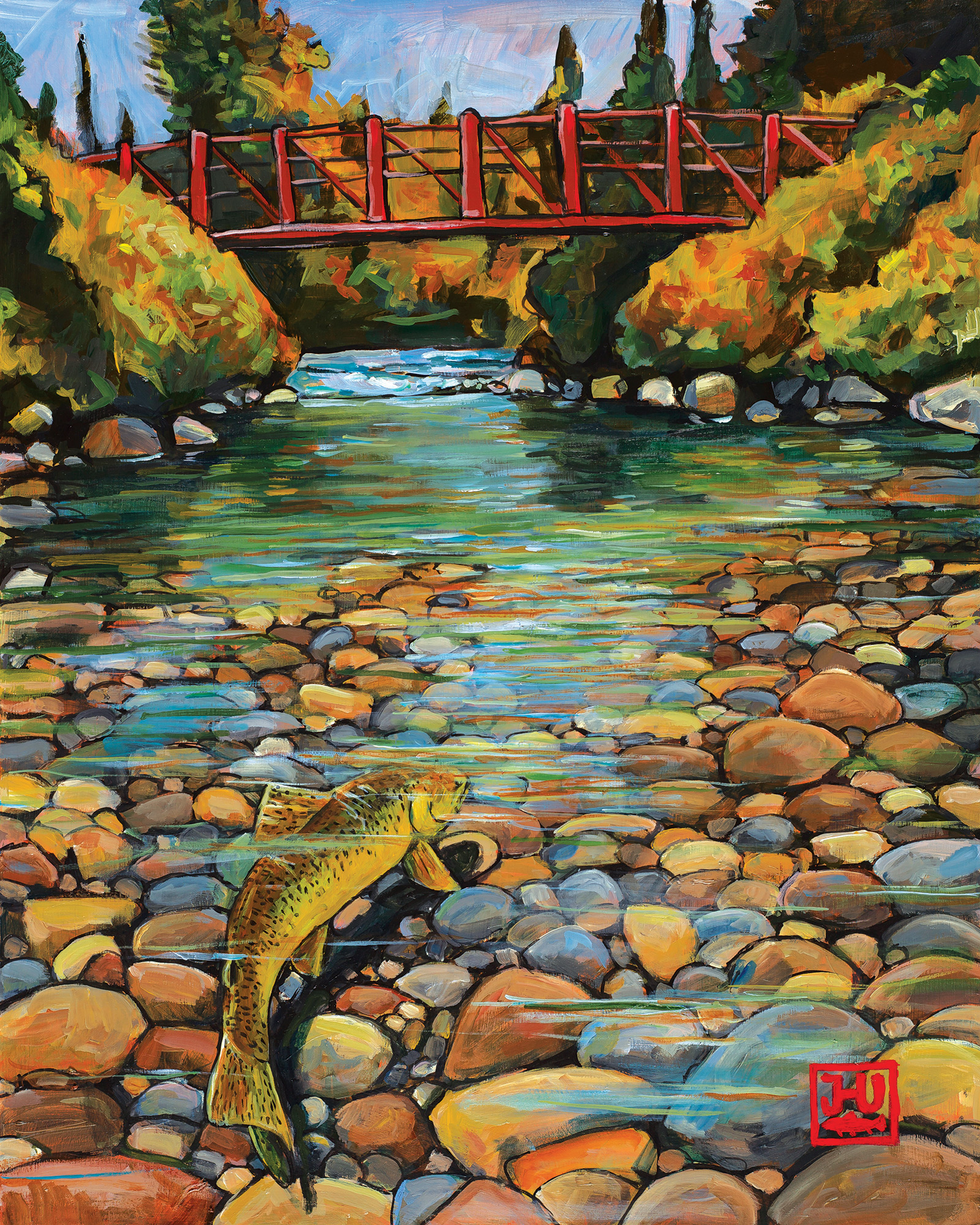

A footbridge crosses the creek at the north end of Greenough Park, a calendar-shot special in elegant balance with the wild creek below, and a near-jungle of feral maples and wild cottonwoods in backdrop. In those days, an undercut root ball along the west bank of the creek upstream of the bridge created a deep lie, exactly the sort of spot that might predictably hold the proverbial big one.

All these years later, I don’t remember what pattern I cast, but likely it was a nymph, a Prince or pheasant-tail, which I fished a lot back then. I do remember the bronze-gong flash deep down in the water, and the sudden, shocking heft of a 17-inch brown trout coming tight to the line.

I played that beautiful, muscular fish back down beneath and then below the bridge, and turned it loose there to rocket away again.

A few nights later, I caught the same fish, in the same dark lie.

The last time I fished the creek that year, in September, I drifted a fly again beneath the overhanging cottonwood, hooking it a third time.

I remember the evening light listing with the tilt of the planet and the season, not quite edged into autumn but not the light of summer either. I remember catching a glimpse of motion on the bridge above as I worked the fish downstream and assuming a walker out for an evening stroll; until I glanced directly up and realized it wasn’t a pedestrian at all but a black bear, padding across the footbridge not 25 feet away.

I guess I can’t definitively call the bear a “big one,” but to me, any bear at that proximity qualified. I started to work the fish back up, against the flow of the creek, away from the bridge. By the time I brought it to hand yet again and cast one watchful eye over my shoulder, the bear was gone. But the exhilaration of catching that big beautiful fish had ratcheted to an all-new high, and I remember thinking in that moment when I let it glide from my fingers and back to its home one final time, that poverty and circumstance notwithstanding, This is why I myself live here.

If I hadn’t popped the question and crashed my Bronco, I never would’ve fished Rattlesnake Creek, or figured out that brown, or spotted that bear.

And no, the marriage, like the Bronco, didn’t last. But the memories of that summer always will. •

Cutthroats by Bryce Andrews

My one, true lake is shaped like a deer in its daybed, and it hangs in a cleft of high, hard mountains like a tear at the corner of an eye. The water is clear as cut quartz crystal. It becomes a mirror when the wind quits, and the peaks are forever leaning in to see their faces. When rages take them, the mountains slough stones the size of pickup trucks and refrigerators. Water closes over these boulders, or nearly so, and the lake heaves up a fraction of an inch. The rocks sleep, disturbed only by nosing trout.

When last I wet a line there, I shared the place with strangers. Suffice it to say that they were vacationing and circumstance jumbled us together. The substance of their professional lives was the ruination at great profit of mountains similar to the ones rising carnassial around my lake. We spoke about it, and of open-pit mining. One of them said: “If we didn’t, somebody else would.”

These captains of industry ate lunch in yellow autumn sunshine and 6 inches of melting snow, and afterward one man crossed to the lake’s far shore. He stood on a stone, casting clumsily while ripples from his fly mixed with the rise-forms of the lake’s abundant, naïve westslope cutts. After scourging the water at length, he caught a slim 10-incher and lifted it by the leader. It made a pretty picture with the peaks behind him and clouds sailing through clear, blue sky in the shapes of cabbages and anvils. Holding the flashing creature toward his companions, he shouted:

“Is this a big one?”

His friends chewed their sandwiches.

“What about it?” he asked again. “Should I keep it?”

No answer came, and after a quarter of an hour his fellows gathered their things. Seeing the shadows lengthen, they struck for the comforts of a lodge. The angler walked last. Passing, he threw the fish into the snow at my feet.

“For your dinner,” he said, and was gone.

Not yet dead but far beyond hope, the fish gulped weakly and regarded me with one dark eye. It was thin as a hatchet handle, half-frozen and weightless in my grip. Having no good way to cook it, I set it in the lake.

In the morning, I caught and released one cutthroat after another, feeling each fish’s electric, jitterbugging strength stir the line and my heart. How could he? I wondered. Why would he take a trout that, fighting on the line, stood in for every fish to ever beat the current — every coho coming home and every marlin tail-walking over the wide Pacific — and pitch it up the bank to die without a reason?

Dipping my hand into the ice-cold, so-very-clear water to slip the hook, I scrabbled at a corner of the mystery, thinking that most of us are alive inside and relatively whole, while a few luckless others are broken where it counts. A person had to be broken, I supposed, to lift a fish and see just his own strength and mastery finning the sky.

When a whole, healthy, living human catches a fish, he cannot fail to be moved by its foreign, submarine strength and direction. As his little leviathan sprints weightless over stones, he knows that the line between angler and quarry, whether made of monofilament or metaphysics, is old, mysterious and worthy. And by the time that fish gulps air, he knows beyond a shadow of a doubt whether it is right to keep the catch for dinner or send it splashing home.

- Painting by Josh Udsen (Detail)

- Painting by Josh Udsen (Detail)

No Comments