03 Feb Fish Tales

To know a place

Written by John Gifford

My wife and I have this ongoing debate: Have you visited a place — a state, for example — if you’ve only spent a few hours in one of its airports? Or by driving through it on the interstate? My wife says no; sitting in the tiny Tucson airport for three hours does not mean that I’ve been to Arizona. I disagree. I tell her that if, for example, a court of law demanded to know where one had been at such and such a time, you’d have to account for each hour — even those spent in an airport — which would mean you’d been in that state.

But can one know a place on the basis of such ephemeral experiences? Of course not. And this is one of the reasons I fly fish. I can think of no better way to immerse myself in a place than by visiting one of its rivers and watching birds glide by, lulled by warm sunshine, fresh air, and the rhythmic nature of casting a fly.

When I started fly fishing nearly 30 years ago, Montana was the one state I wanted to fish in more than any other. This had nothing to do with that film from the 1990s — which I hadn’t seen — but rather the vast, sparsely populated landscapes and the network of wild, trout-filled rivers I’d read about in books and magazines.

Over the years, I managed to acquire a couple of prized fly rods built by some of Montana’s most skilled artisans. But, for various reasons, it took me nearly three decades of serious fly fishing before I made my first visit to the state in the summer of 2021, when my wife and I enjoyed a pleasant week on a ranch outside of Darby. There, I could simply walk out our cabin door and cross the highway to enjoy casting flies to the Bitterroot River’s cutthroat trout.

I did this for several days, and one afternoon, I caught sight of a bald eagle soaring upstream and alighting in a pine tree directly across from the run I was wading. Together, we fished this stretch for 15 minutes or more before the eagle spread its wings and flew away. Seeing this living symbol of freedom, of America, was a captivating experience and one that significantly enhanced my sense of place in the Northern Rocky Mountains.

When the day finally came to fish with Ryan, a guide I’d booked months in advance, I shook his hand upon meeting him and asked him how the fishing had been. “Not very good,” he replied to my surprise. I’d waited all week, all year, all my life, it had seemed, to fly fish in Montana, and now my guide was telling me, in essence, I should have gone to Wyoming or Idaho. “This river gets pounded,” he explained.

“It’s been fished hard all summer long.” This was a prospect I hadn’t considered. Wasn’t the fishing always good in Montana?

“I bet I have a fly or two they haven’t seen,” I offered.

“There are no flies these trout haven’t seen,” Ryan responded. As he wheeled his pickup truck into the launch area, he pointed to the empty parking lot. “See, when the fishing is good, this place is full,” he said.

I was mildly discouraged but determined to make the most of the day and the opportunity I’d waited so long to experience. Besides, I was fishing in Montana. This, alone, was enough to put a smile on my face.

Ryan tied on a two-fly rig consisting of a large, bushy indicator and a large, bushy dropper fly beneath it. What most impressed me — and the fishery’s telling detail, as far as I was concerned — was the heavy 4X tippet he used. I was accustomed to using Gossamer 7X for the tailwater trout back home in Oklahoma, so 4X was a luxury. It was also insurance for when a large trout, head shaking, might lunge and run.

“These fish aren’t line-shy, especially with the water being a little off-color today,” Ryan said. “But they won’t tolerate any drag in your drift.”

It was nearly an hour before I caught my first fish, a 14-inch cutthroat that put up a spirited fight against my 5-weight. Ryan perked up as he reached for the net. “Good, John,” he said. “This is great. Great job!”

The fish seemed to break the ice between us, and afterward, Ryan seemed much more at ease. “A lot of my clients come out here thinking they’re going to catch 20 or 30 fish,” he said. “But they’ve picked up a fly rod only once or twice in their lives. I spend most of my days untangling lines and giving casting lessons. Yesterday, I had to remove a hook from someone’s wrist.”

I got it: his negativity was a learned behavior, a way to reset his client’s unreasonable expectations. After tangling many lines over the years, I’d learned how to avoid this, giving me more time to ask Ryan about the kingfishers and cottonwoods along the river, weather patterns, and stories about local wildlife.

We spent the day floating past bucolic fields, with birds singing, insects humming, and sunny mountains looming in the distance. These were the same landscapes I’d dreamt of finding in Montana, and now I was seeing them in person. The sky was clear, immense, and cerulean blue. It was the perfect day to float down a classic Western trout river, fly rod in hand.

After lunch, and a history lesson about the area’s early settlers, I rolled my flies out into a bubble line and watched as the big attractor was yanked under. I set the hook into a larger cutthroat that pulled hard. After a five-minute battle, Ryan dropped the anchor and stepped into the river. As he lowered the net, the trout jetted out into the current and far downstream. I spent another five minutes fighting the fish, as my reel purred with each surge and run.

When Ryan finally netted the trout, he told me it was the largest anyone on his boat had landed this season. It was a gorgeous fish, golden-hued and speckled, as beautiful as the surrounding landscape. I smiled as it slid from my hand back into the river.

We were still three hours from our takeout point, but already the day was a success. We hadn’t seen another boat, and the fish weren’t numerous, but they were healthy and strong. The river was gentle, the current smooth and steady, and the leaves on the cottonwoods lining the banks seemed to quake with applause. I thought about the bald eagle from earlier in the week — its immense wings, long yellow beak, and bright white feathers — as it soared along the river in relief against the forest of pines behind it. That sight, the cutthroat’s speckled flanks, the sunny fields, the distant mountains, and the meandering river were the most memorable catches of the trip, the ones I would relive again and again after returning home.

At every bend, I found myself a bit more immersed in this special place, as I soaked in the sights and sounds of the Bitterroot River. And, when the third trout hit my fly, I told myself I was beginning to get a feel for Montana.

Camouflage

Written by Dick Donnelly

The other day, I sat on my porch cleaning fly line. In my opinion, there’s not enough time to do these things. If the day is sunny and wind-free, I want to be out on the water. If there are thunderstorms, my wife expects me to stay inside and work on our 110-year-old house. Does a house this old really need work? Yes, about 110 years’ worth.

On this particular day, it was raining steadily. But instead of replacing the cracked laundry sink or painting the guest bedroom, I spent a pleasant hour buffing fly line. If you are neglecting this task, I suggest you correct this immediately. Use a bucket with diluted dish soap. Wipe the line clean using a soft cloth, then rinse it with fresh water. You won’t believe the gunk that comes off, the dirt and algae. Dry it with a clean towel and buff it with line conditioner — personally, I like car wax. Then stand back. The next time you fish your rod will fire like a bazooka.

I hear my wife calling me and freeze. I’m sure she has a chore for me, and I’m in danger of being taken from an important, pleasurable task and given an unimportant, unpleasurable one.

The seconds tick by. Dressed in a blue T-shirt and brown cargo pants, I blend perfectly into the wicker chair and cushions. The floor creaks. She pauses at the screen door, then walks on, the danger passing like the shadow of a hawk.

Years of fly fishing has taught me an invaluable lesson. That lesson is camouflage. When correctly deployed, one becomes invisible. To trout. And your wife.

Today we shall stick with trout and the disturbing trend of ornamental fly-fishing gear. This includes hats with brightly-colored logos; shirts in bright blue, lime, and electric yellow; and vests trimmed with jaunty orange pockets. Clothes like this might help you blend in at a local Trout Unlimited meet-and-greet, but not at a local trout stream.

As fly anglers know, when trout sense danger they don’t bite. When unsettled fish spot something they don’t like (usually you), they point their noses upstream and stop feeding, entering a hold-and-wait pattern. Trout, after all, have splendid vision: I can personally attest to having my #16 Blue Dun refused after they were just hitting my #18. We may not be able to tell the difference, but they sure can.

Trout see color, as well. The next time you net a spawning brown, take a moment and turn him over. With bright gold belly fins and red side spots, they’re as brilliant as toucans. And they need to be: The sharp dresser gets the girl. (Not to wade too far astream, but some of you single fishermen might take note.) But when you place the trout back in the water, he seems to vanish instantly. Looking closer, you might see a fin move; he’s still there, but he’s invisible. The brown trout may be one flashy fish, but not when viewed from above; its deep-green back, mottled with closely-grouped spots, works as camouflage. A hunting eagle can’t see him.

Nature always has a lesson, and camouflage is one of her greatest. Like eagles, trout have keen eyesight, meaning that everything anglers wear needs to match the foliage. If it’s early spring or mid-fall, with the dominant colors of dormant grass, wear a buff-colored shirt. In summer, olive greens and patterned camo are safe bets; the kind turkey hunters wear are ideal.

What to do with that pricey fishing vest with orange-trimmed pockets, or that favored hat with the electric blue Rob’s Rippin’ Rainbows logo? Throw them out. (Just kidding.) Buy a brown felt-tipped pen and, though it will hurt a little, color over the orange pockets and the logo. The fish will thank you. Or rather, curse you.

And don’t forget your face and arms. Keep your sleeves rolled down. For those with pale complexions, consider a bug mask. I personally wear a camo bandana — bank robber-style — when in close proximity to feeding fish, particularly if I can’t avoid standing in the sun with my face glowing like a searchlight.

I realize I’m emphasizing small stream tactics and close casting scenarios, but you can adjust my advice accordingly. Anglers can probably get away with anything from a drift boat, launching massive casts at unsuspecting cutthroats on the Kootenai. This is the equivalent of duck hunting from a helicopter, where camouflage would likewise be unnecessary.

Camouflage is one way to keep Mr. Trout from seeing you, but not the only way. The other is to just plain hide. We’ve all seen those who bank fish or walk boldly up to pools. Don’t be that angler. Instead, get in the water and stay in the water, which creates the lowest profile. Walk slowly, keep foliage behind you, and, if possible, stay in the shade. Creep up behind beaver dams and fallen trees. Crouch when approaching a good lie. Think of your living room window with a good view; the trout’s whole world is a living room. Reducing your visibility will make all the difference, especially with skittish and overworked trout. And, these days, what trout aren’t skittish and overworked?

Incidentally, my wife found me that day despite my camouflage. I snuck from the porch to the basement, where I sat quietly organizing my fly bench until she put me to work replacing a light fixture. A pretty good sportsperson in her own right, she used the time-tested strategy all anglers eventually learn: They gotta be somewhere.

A Sublime Waste of Time

Written by Jeff Beyl

Sometimes the subject comes up. You know how it goes: You’re at a party or gathering — or maybe you’re sitting next to someone on an airplane making small talk — and the question is put to you: “So, what do you like to do for fun?”

I always think they expect me to tell them that I bowl, or play in a local softball league, or that I like to golf. But, I don’t. Instead, I like to have a little fun with them. I might tell them I enjoy studying the attack patterns of great white sharks, or something like that. I told one guy that I raise wasps; not honey bees, wasps. For fun. He gave me a strange look and quickly opened a magazine.

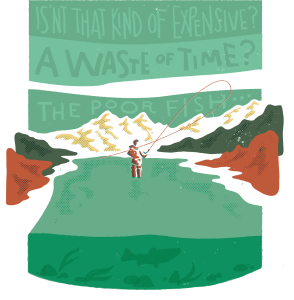

I love all the different types of reactions I get: Wow! Really? Oh my! But when the subject comes up, and I do occasionally tell the truth — that I am, in fact, an avid fly-fisherman — I also get many assorted responses, remarks, judgments, and criticisms. If you also cast the occasional fly in search of elusive trophy trout, you have most likely heard one or two of the following:

“Fly fishing? Nah. Too difficult. Me? I’m a bait fisherman.”

“Isn’t that kind of expensive?“

“You don’t keep any of the fish? Why not? Isn’t that a waste of time?”

“The poor fish. You just drag them around the river.”

I’ve heard many other comments from the peanut gallery, but to the ones above, my responses have included:

“Oh, you’re a bait fisherman? Well, you’re in good company, so was Ernest Hemingway.” (This is true, by the way.)

“Difficult? Yes, it can be, but that’s what makes it challenging, fun, and rewarding, like learning to play the violin.”

“Expensive? Yes, it can get expensive, but have you priced out a good set of golf clubs lately?”

“Why don’t I keep the fish? I respect the land, rivers, and fish; to protect those resources, I practice catch-and-release.”

The poor fish comment, though? You’ll probably never win this one. I could launch into a discourse about how the fun is in hooking the fish and seeing it jump — sometimes clearing its whole body from the river amid a rainbowed spray of water — not mercilessly yanking the fish in. I could explain that once the fish is hooked, we bring it in as quickly as possible and release it gently back into the river, but that doesn’t always placate the inquisitor. Instead, I usually try to extricate myself from the discussion. I may start looking for my wife, ask where the men’s room is, or tell them that I also climb frozen waterfalls and surf giant waves.

Another way I’ve found to extricate myself from this type of conversation is to turn it around, point it back on them, and put them on the spot. “What is your favorite smell?” I might ask. Or, “Hey, let me ask you, do you think the big toe feels self-conscious about being the big toe?” Or, “If you could be any fictional character, who would it be?” If they say Batman — and, believe it or not, sometimes they do — I then ask them the question that the Joker once asked of Bruce Wayne: “Have you ever danced with the devil in the pale moonlight?”

I was flying across the country recently with my fly-rod case on the floor by my feet. The guy sitting next to me took a sip of his coffee, looked over, and asked if I was an architect. “That’s a blueprint in there, right?” he asked, pointing to the case.

“No, this is a fly rod,” I said.

“Ah, I see. You’re a fisherman.”

“I’m a fly fisherman,” I said. (For some reason, I always feel the need to be specific about this.)

“I don’t fish, never could get into it,” he responded.

I pondered, for a quick moment, wondering why he would feel the need to share this with me. I considered telling him that I was also a rodeo clown.

“Well,” I said, “I suppose everyone has their own idea of a sublime waste of time.”

No Comments