24 Jul Fish Tales: The Chance of a Lifetime

ANYTHING CAN HAPPEN

By Charlotte McGuinn Freeman

When you move to Montana you get a lot of questions, especially “do you fish?” It’s Montana after all, and they imagine A River Runs Through It — that whole romance of western fly fishing — the solitary figure throwing out larger and larger loops of line in waning light on a sun-dappled western river. “I’d love to fish Montana,” they say, their voices trailing off.

It makes me sad, those wistful voices, those people longing for the fleeting chance of a lifetime. Because the thing is, I don’t fish the famous river that flows through my town, the one where boat after boat goes by all summer, filled with men in waders, casting with the urgency of people who only get a week or two off each year and who are determined to make the most of it. When I fish, I want to fish like a kid. I want that sense of suspended time, the sense that there’s nowhere else to go, and nothing else to do, and so you’re just going to throw your line back in there one more time and see if something might happen.

For instance, it’s evening and we’re camped by a pothole lake in the Russell Wildlife Refuge. There are two white pelicans fishing for their dinner over by the island, a crowd of noisy dabbling ducks in the rushes on the far side, and the surface is dappled with those little rings fish make when they come up to feed. I throw out a fly, and despite my best efforts, yell “I got one!” when the fierce little fish takes it. I fight it for a bit, then swing it up and out of the water, and in a movement as familiar to me as any from my childhood, I run my hand down to smooth the dorsal spines before taking out the hook. What I’ve caught on that pretty lake in the Russell isn’t a trout, it’s a bluegill — the bright spot of gold beneath its chin, the spiny dorsal fin, the aggressive fight. The familiar feel from those years of childhood, standing on a Wisconsin dock, catching the same little fish over and over. Bluegill and me, we go way back. That night, we cast flies while bats swooped over the water, catching bluegill and bass out of a warm weedy lake as light faded over the badlands of eastern Montana. Was it fishing? Of course, just not the kind the tourist board usually advertises.

For me, the magic comes from wading up some creek in my Chuck Taylors, a box of flies stuffed in the back pocket of a pair of shorts, hoping for a big lunker underneath an overhang, but happy to see what I can get. Sometimes it’s the surprise of a bluegill on a fly rod. Sometimes it’s a 6-inch trout, so small that to this transplanted Midwesterner it looks like the minnows our dads used for bait. Sometimes it’s a big old brown trout who’s been living under that log for years. You never know. That’s the fun of it. Because although living in Montana for most of us means that we don’t have much cash, and don’t go on real vacations, it also means that we’ve got the space to take off for a couple of days mid-week, throw our gear in the car and drive up some logging road, to explore a new corner of the state where we’ll find a creek, or a beaver pond, or even a stocked reservoir in the middle of nowhere, and where we’ll have the chance to throw in a line, to see what might happen.

DOUG’S BUCKET LIST

By Greg Keeler

It’s the trip of a lifetime,” I said to our cat, Doug, one morning last summer as I lured him into his plastic carrier, then set it on the passenger’s seat of my pickup. “Time to go fishing.” Even though a woman down the block thinks it’s a sin to give pets human names, my wife and I call our massive, black shorthair “Doug” because we’re loathe to utter nicknames like Baron Van Snugglebug.

The negatives to this expedition might seem obvious to most readers, but I’ll enumerate a couple here for the sake of contrast. Like many cats, Doug is horrified at the prospect of water. At home, he’ll only drink from a small bowl that has a rug under it and is wedged safely in a corner. If I carry him anywhere near a sink, tub or toilet, his legs go like propellers until his claws latch firmly onto anything in proximity (arms, clothing, face, etc.) to avoid the possibility of a dampening. I was also apprehensive about such a sojourn owing to the possibility that, once I opened his carrier near the river, he would bolt for the top of a cottonwood and offer himself up as fodder for woodland critters.

On the proactive side, I don’t have a dog and have always envied anglers who take their dogs fishing, even though dogs will dash into the water to retrieve a hooked fish. Lord Fuzzy (OK, I lied about nicknames) has always been particularly dog-like in his loyalties, attempting to follow me on walks and romping through the front yard to greet me when I return from work, so maybe, I rationalized, he’d have a dog’s affinity for fishing. Lending to my sense of urgency on the matter, Dr. Chubbyromp was over 15 years old, and the previous spring he had suffered a brush with the grim reaper when the vet removed a ball of pus the size of an egg from his groin. All said, I was determined to put fishing on Doug’s bucket list.

So that afternoon I drove him to Williams’ Bridge on the Gallatin and lugged his carrier about 100 yards upstream, careful to stay below the high water mark and avoid the wrath of Ted Turner’s minions. When I set Doug on some rocks next to the river and opened his hatch, he didn’t budge, so I reached in and he nailed me good.

After telling him to go screw himself, I proceeded to cast, immediately side-hooking a pig of a whitefish and working it into the shallows before Fatso’s plastic box. All that quivering fish was too much for him, and he stuck his front half out onto a rock where he took a couple of bats at it so that it drenched him and went screaming for deep water.

These days, Doug seems to have acquired a second wind, pursuing his toy mouse around the living room with the avidity of a kitten, perhaps so he won’t appear so pathetic as to require a bucket list and another trip of a lifetime.

FATHER FISH

By Toby Thompson

My father and I had fished together from Montana to the Florida Keys, but the last place we fished was where we’d begun — in the Potomac River near Washington, below the house where I’d grown up.

He had not wished to. “I’m not lugging that canoe down that hill,” he said, irritably.

“I’ll carry it,” I said. “And the paddles. You carry our rods.”

He was in some pain, and his physician’s hands, which had comforted many, were liver-spotted and twisted with arthritis. I felt that if we did not fish this month, this day, we might never.

“River’s clear,” I said. “We’re guaranteed a bass.”

He snorted.

The Potomac, northwest of Washington, is a picturesque rock garden with classic stretches of pocket water and fine smallmouth-black-bass angling. We had stalked fish there since I was 6, he carrying the rods as he did today, as his father had for him, to the same water, 66 years previous.

My father took the bow and I pushed off from a landing where, during the 1950s, we’d have embarked in a john boat poled by one or another West Virginia outdoorsmen. My father enjoyed their company, laughing at their tales as he marveled at their handling of heavy boats in fast currents. I was no West Virginian, but I angled the Grumman past rocks and through eddies as my father cast.

He used a spinning reel, and each time he flicked his lure he winced. Rheumatoid arthritis is no picnic and he cast where he had small chance of taking a fish. Two years earlier I had guided his best friend on a terminal jaunt, and when he’d hooked a tail-walking smallmouth had exclaimed, “Thank you, thank you!” Not to me, but to the fish.

I had grown up spin casting and in the past decade had become a competent fly fisherman. My father was skeptical of this talent, so when a bass hit my streamer, leapt repeatedly as I played it against the current, he watched it dive, charge and leap again with wonder. “Good boy!” he said. The day’s first smile crossed his face. He should have netted it for me. But I netted it myself, as I’d net fish the rest of my life.

Smallmouth fight defensively and with great vigor. As the creature slapped the hull and I struggled to disempale it, a montage of angling scenes flooded my mind: of us in the Everglades fishing for snook, on the Chesapeake taking blues, in Minnesota horsing Great Northern Pike, in Montana hunting cutthroat, and of thousands of days on the Potomac.

I lifted the bass, its bronze back dappled with obsidian, and my father reached out. He held it flat in his age-spotted hand, an act which calmed them both.

“We could keep it,” I said.

“No. Let it live.” He slipped it across the gunnel.

I cast several more times, then shoved off, letting the river ferry us downstream. It was a crystalline summer evening, with ospreys soaring as geese skidded in for the night. I shouldered the canoe at our take-out point, and my father gathered the rods, blanching. Neither of us spoke as we climbed the hill.

At the car, breathless and in pain, he tried a joke: “The fucking you get is not worth the fucking you get.” I laughed with this fist-shaking at old age. He might have said “fishing,” though I knew he would not.

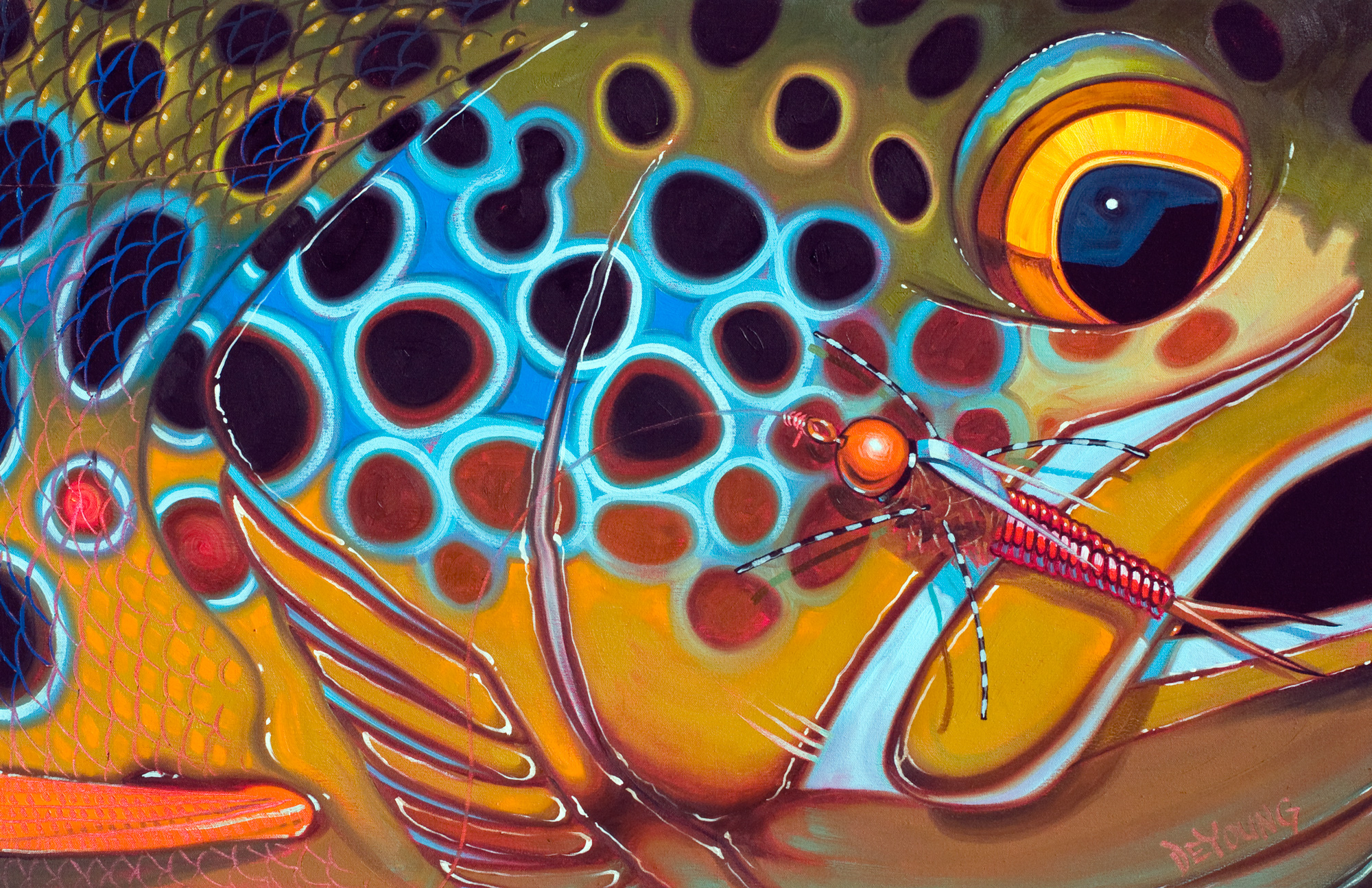

- “Brown Rubberlegs,” illustration by Derek DeYoung

- “Boundry Waters Bass” illustration by Derek DeYoung

- “4-in-1 Full Emerald,” illustration by Derek De Young

No Comments