12 Aug Fearless Beauty

Dana Boussard’s work balances the personal and political, as evidenced by her subject matter, which broaches topics of women’s issues and the environment through a deeply intimate lens; and her method of working, which ranges from solitary studio time to large public artworks installed in capitals and federal buildings throughout the country. However, the artist remains committed to living life sparingly amid nature on the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana.

Dana Boussard in her studio.

It was not always this way. Born in Choteau, Montana, Boussard attended St. Mary’s of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana, then transferred to the Art Institute of Chicago, where she first learned her craft and observed career artists at work. Seeking to embrace an artful life, she relocated to New York City when she was in her early 30s. A fortuitous encounter with Stan Reifel, the executive director of the fine-craft venue Fairtree Gallery where she was showing, led to a lifelong union. The couple decided to move their life together back to Montana at a pivotal juncture in Boussard’s career, a time when she was finding her artistic voice and developing a recognizable style. Reifel’s expertise as a furniture designer and master craftsman helped her to enter the public art realm, scaling her work for increasingly complex and dramatic architectural spaces. “My husband’s skills and his belief in the work is the reason I have been able to accomplish what I do,” she says.

The contemporary fiber-art movement gained momentum in the 1960s and ‘70s in tandem with the women’s movement and the rise of feminist art. “My fiber work started at the University of Montana,” Boussard recalls. Realizing that the printmaking process was not giving her immediate satisfaction, she preferred the direct interaction with fibers. “My work was becoming larger and more involved. I applied for my first commission at the University of Oregon and realized it was a good direction that suited me. I liked the idea of putting something into a public space and having it get out to a wider range of audience. I decided from then on to pursue that direction.”

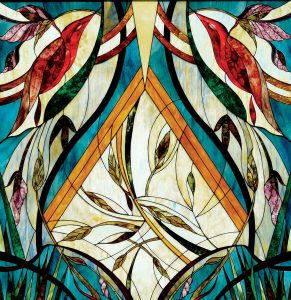

“And You Are the Branches” detail | Stained Glass/Copper Foil | 6 x 6 feet

Returning home to nature revived a symbolic language for the artist. “Aesthetically, I’ve been on this piece of land for more than 35 years,” she said. “I see myself living and being immersed in the natural world; the deer and flocks of birds that move through here, the diversity of flora and fauna. Part of that is living on the reservation. Residing here, I continually reflect that this was the land the First Peoples inhabited, and now I am here. I live within this history daily and it has entwined itself into a part of my aesthetic. I like the drama of the changing landscape, its continuum over time. I’m not a person who is specific in telling my story. I use symbols: the bird as a symbol of our spiritual self, the house as a symbol of shelter. It’s elusive and hard to tell how viewers see things. It’s not always literal. It’s how I’m feeling. Why do I use barbed wire? Because among all the beauty of the narrative, a more complicated story unfolds.”

People bring their own interpretations and observations to the experience of viewing Boussard’s art, weaving their own stories with those of the artist. “Each of my drawings, paintings, fiber works, and glass installations is a visual narrative that tells a story and speaks to issues that touch me deeply and personally. Throughout my career as an artist, I have always felt that art can make a difference, and with that belief has also come a passionate interest in public art that mirrors my studio work. I continually find that creating art for public spaces gives a broad and tangible voice to my story. It is with these beliefs in the power of the visual voice that I go to the studio each day.”

“And You Are the Branches” | Center Altar Window Stained Glass/Copper Foil | 42 x 8 feet | Holy Spirit Catholic Parish, Great Falls, Montana

In Boussard’s drawing, Montana on my Mind, a spirit figure floats over the Western landscape. Her trademark birds are present, perched on barbed wire, raising issues of freedom and restriction. Also present is a shelter in which the skull resides. “The floating image, that is partly nature; you see the wheatgrass flying out from her hair,” Boussard relates. “She’s imbedded in the house also. The house has great influence on how I work. I see it as the house inside of ourselves — like our soul. Does it stay closed? Does it say we don’t let anyone in, and we don’t let anything out? Or is it something that can change from place to place? Is it something that influences us directly — which I believe it does. Where we grow up, how we live, and how that movement to adulthood happens inside the house. The house seems very metaphorical as family, and shapes who we are.”

Watch from the Outside, Speak from the Inside continues the thematic presentations of shelter, birds, barbed wire, and pears that also occur in Montana on My Mind. The shelters are snared by barbed wire or crossed out. Boussard states that, “Montana can no longer be viewed as just another pretty face. It is the purpose of art to see the changes that are upon us, and to respond in a highly provocative way. In studios across Montana it is time to ask: Are we just trafficking in images and what is their power? That home on the range might just be behind a refinery.”

Her latest stained glass commission, And You Are the Branches, is her magnum opus. It took 10 years from conception to execution, is comprised of 40 panels of 15,000 cut glass pieces, and was installed in the Holy Spirit Catholic Church in Great Falls, Montana. Boussard worked closely with glass fabricator Dennis Lippert, as well as the church architect and clergy, who helped her visualize the potential of the project: one that would inspire and lead congregants to worship in beauty.

Boussard was given artistic latitude, while considering the aspirations of the congregation and the local interpretation of Christianity. She drew upon her 1986 stained glass commission at Saint Joseph Church in Choteau, Montana, cognizant of the challenges and rewards that lay ahead. Her designs took into account the architectural space, the natural environment, translucency, light, and how movement from ground to sky would instill an uplifting worldliness to congregants in the chapel. She painstakingly selected the colored glass with nuanced colors and textures, incorporating her trademark flowing ribbons and birds in flight. The only direction she was given regarding subject matter was to include wind and wheat, two commodities the Great Falls area has an abundance of.

“Collected Parts of a Shattered Forest” | Oil on Pieced-and Stitched Canvas | 78 x 58 inches

The first set of windows, installed behind the altar, soars 42 feet high and 8 feet wide in a triangular formation, and contains undulating, variegated colors punctuated by wheat chaff and red birds, a unity of earth and sky. The completed interior reflects Boussard’s firm commitment to the idea that art holds the potential to lift our spirits even while engaging in a contemplative manner with our place in the world.

While state and national arts organizations have bestowed numerous awards on the artist, she says her most satisfying roles have been as a staunch advocate for the arts, the environment, and social issues. But perhaps her crowning reward has been her ability to reside in a land that she has loved from birth. “But where you live defines who you are,” she says, “and many artists in the early ‘70s began to ‘see’ in a different way. Many saw that isolation was the state’s best asset, and that the past had to be remembered to make a future.”

Boussard’s hallmark is to say something that comes from a different place, in a different way. “That’s the charge I’ve given myself — to make that attempt. I want my work to be a narrative, interwoven between time and culture. I want my work to say something. I want it to mean something.”

Watch from the Outside, Speak from the Inside | Oil Stick and Colored Pencil on Paper | 30 x 44 inches

Watch from the Outside, Speak from the Inside | Oil Stick and Colored Pencil on Paper | 30 x 44 inches

Boussard has created an evocative vocabulary composed on the spectrum between fact and fiction, the spiritual and concrete. Her dreamlike compositions pay tribute to nature, known and unknowing, mining it for its symbolic potential.

No Comments