23 Jul Images of the West: Fallen Heroes

LOOKING OUT TO THE HILLS AT THE Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument site today, one can see the eerie white tombstones memorializing American soldiers who fought with the 7th Calvary in 1876 under the command of General George Armstrong Custer. Numbering more than 200, the stones jut from the windswept hillside at Crow Agency, Mont. They are like teeth, no longer sharp, but aging, crooked and decayed; the tombstones are markers of the historic battle that from its fatal end launched scrutiny by historians.

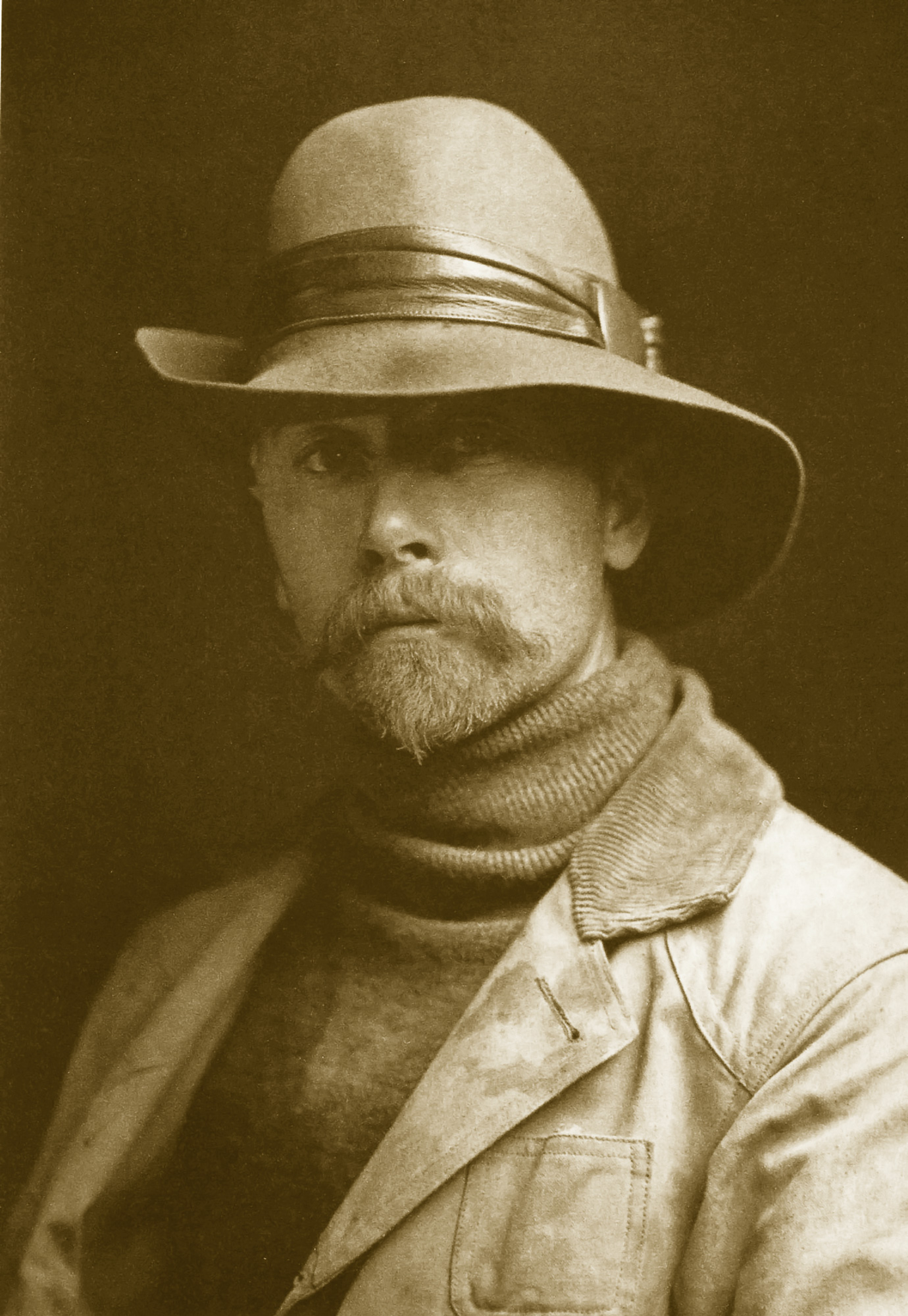

In 1907, photographer Edward S. Curtis tried to understand the story of what was then known as “Custer’s Last Stand” from the Indian perspective. At some point in the summer of 1907 Curtis wrote, “No one can accuse Custer of lack of bravery, and he was a good Indian fighter, or in other words a good general in Indian campaigns. Was he that in his last fight?”

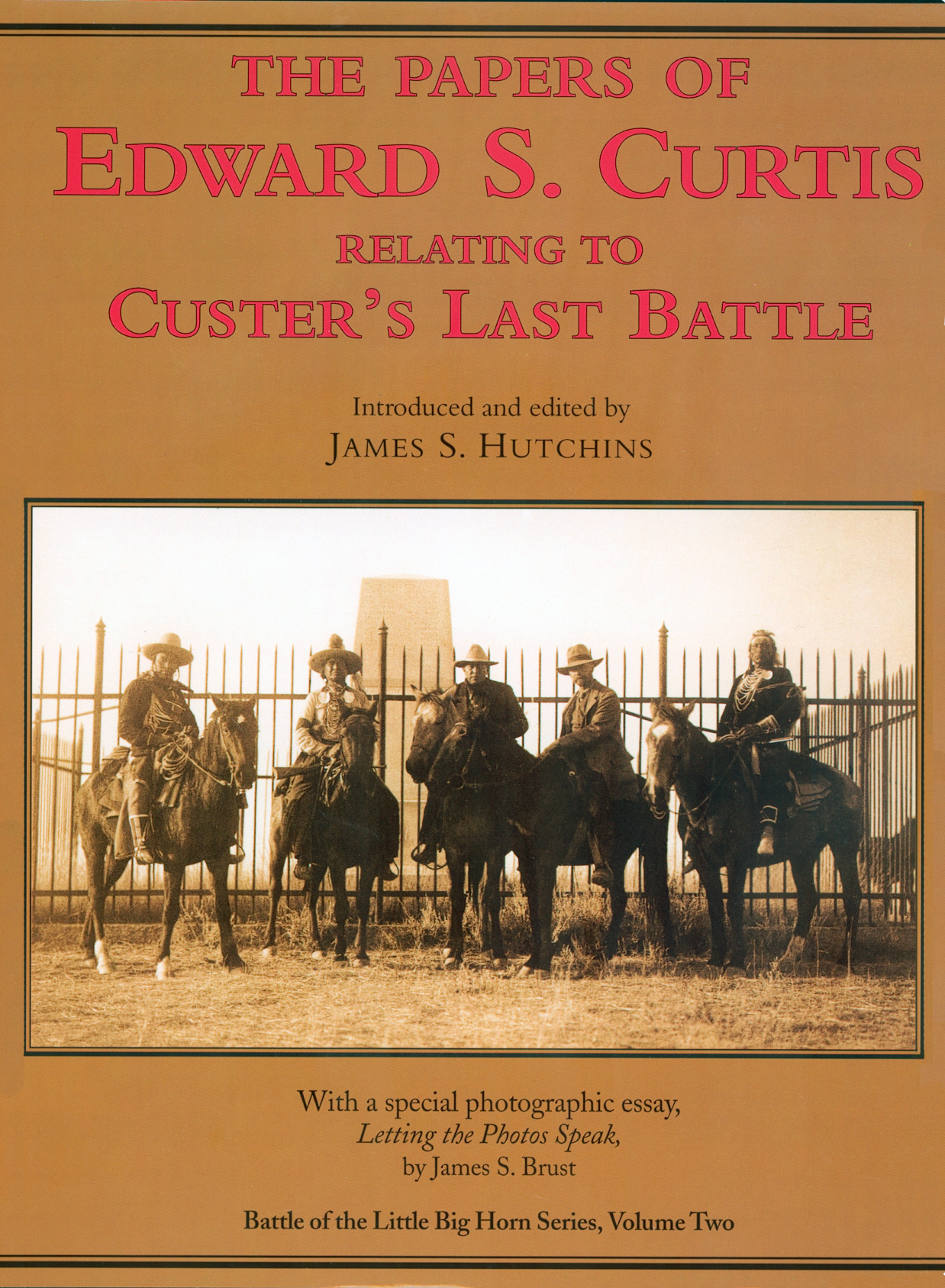

The answer to the question Curtis posed in his personal narrative, “Notes on Custer Battle and Field” spurred a three-year personal investigation into the June 25, 1876, defeat of Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer at Little Bighorn. “Notes” is one of several documents Curtis either wrote or acquired about the subject that were later presented in The Papers of Edward S. Curtis Relating to Custer’s Last Battle.

Those who are familiar with Curtis’ photography of Native Americans know of his 20-volume work, The North American Indian, a written and pictorial historical record of Indian peoples. In an early volume devoted to the Teton Sioux, Curtis, known among the Indians as the “Shadow Catcher,” intended to present an account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn from an Indian perspective.

Fieldwork for the project began in 1905 with a visit to the battleground. There he acquainted himself with the topography and interviewed several Sioux warriors. While the aging warriors could recount their personal actions in the battle, they were unable to present a coherent account of the engagement as a whole, and in terms Curtis could understand.

He enlisted the help of White Man Runs Him, Goes Ahead and Hairy Moccasin, three Crow Indians who scouted for the 7th Cavalry during the 1876 expedition. In June of 1907, Curtis and the scouts, along with a Crow Indian interpreter, retraced Custer’s route across the battlefield. In “Notes” Curtis wrote:

“I have ridden it with our blood all tingling with the swing of our horses as we galloped across the plains, clearing gully and hummock with a clean spring, the Indians singing the medicine songs of that day thirty years ago.”

The group stopped at various sites, and the scouts described the events and actions of Son-of-the-Morning-Star, the Crow name for Custer.

How Custer’s famous last stand unfolded is still debated among Little Bighorn scholars who have studied the engagement in exhaustive detail. The most accepted account has Custer dividing his command into three battalions on the morning of June 25. He sent three companies under Major Marcus Reno in a direct assault on the Indian encampment along the Little Bighorn River with the promise that he and the rest of the command would quickly follow. Three more companies under Captain Frederick Benteen moved in a sweeping arc to deter the Indians from fleeing. Custer and his five companies advanced northward along the bluffs east of the village. In short order, the officers faced an encampment grossly underestimated in size — possibly as many as 7,000 Sioux and Cheyenne. Within minutes, well-armed warriors — perhaps numbering as many as 2,000 men — rallied and began a ferocious pursuit of their attackers. In the end, Indian casualties numbered around 100. The 7th Cavalry suffered 225 casualties. Every soldier under Custer was killed.

For Curtis, the battle’s pivotal point, as related by the Crows, occurred atop Weir Point. From there, the scouts and Custer watched warriors armed with bows and arrows, firearms and war clubs swarm Reno and his troops. With no reinforcements in sight, Reno halted his command, dismounted and formed a skirmish line. According to the narrative of White Man Runs Him, as recorded by Curtis:

“Custer was watching them all this time. I was coaxing Custer to fight, but he said: ‘Let them fight. We will have our chance.’”

Shortly afterward the scouts departed, released from their duty and advised to “save your selves.”

Curtis was certain the scouts spoke the truth. At the same time he realized their story belied widely accepted beliefs affixed to Custer’s defeat: chief among them was that Major Reno’s betrayal of Custer was prime cause for the debacle. Had Reno pressed an aggressive attack as expected of him, Custer would not have been left to wage a desperate struggle. In the Crow accounts, however, Reno was the betrayed and Custer the betrayer. In “Notes on Custer Battle and Field,” Curtis wrote:

“The point I want to make clear is that, according to this evidence, Custer sat on this high point and saw Reno make the mistake of dismounting his troops — if it was a mistake; saw the opening of the fight; the men beginning to give way slowly at first, then in confusion and disorder, little groups here and there making their own stubborn fight without a commander to properly direct them, men trying to pick up wounded comrades, trying to drag them to concealment in the brush; saw and must have known that Reno had lost control of his command … watched all of this from 45 to 60 minutes … and that whole fight was so close to him that he could have been in the thick of it in five minutes … had he got to the aid of Reno, the Sioux would have been routed in half an hour, without doubt.”

Curtis grappled with the best means of presenting his discovery. Perhaps his friend, President Theodore Roosevelt, would appoint an official investigation into the battle after reading the Crow scout narratives. Before approaching Roosevelt, Curtis wisely consulted officers of the Regular Army familiar with the battle and “without pronounced partisan views” toward it.

Curtis found accord with retired Major General Charles Roe and retired Brigadier General Charles A. Woodruff. Perhaps because he found Lieutenant Colonel William Bowen’s reaction disappointing, he omitted Bowen’s correspondence from the papers that he sent to the president. Roosevelt, a staunch supporter of Curtis’ The North American Indian, also staunchly supported Custer, and wasn’t at all disposed to muckraking his heroic image. In April 1908, Curtis wrote to Woodruff:

“The President’s thought is that I am taking too large a responsibility unto myself … and as I am not strictly a historian, it would be better to leave this matter to someone else and cling closely to my Indians.”

Curtis abided by Roosevelt’s wishes and struck the episode at Weir Point from his text. The sanitized Sioux volume of The North American Indian passed into print at the close of 1908.

Eighty years passed before Curtis’s son, Harold, age 95, donated his father’s papers to the National Museum of American History Smithsonian Institution. James S. Hutchins, the senior historian, compiled and presented the documents in the book, The Papers of Edward S. Curtis Relating to Custer’s Last Battle.

The wealth of information now available to contemporary Little Bighorn scholars was unfathomable in Curtis’s time. Thus, when the book was released in 2000, it did not generate the sensation Curtis might have imagined.

John Doerner, chief historian at the Little Bighorn National Monument says, “The book was just another interpretation of the battle and added to the controversy surrounding it. Scholars look at the Curtis papers and all other perspectives. It’s also important to understand the complexities of the battle, the historical and archeological record, the placement of the bodies, the conduct of the officers and soldiers, the timing and the terrain. When you take all of it into consideration, the more you support George Armstrong Custer. However, when you consider Curtis’ understanding of the scouts’ accounts, that he and they were unfamiliar with cavalry tactics of the time, and that they had hindsight, it’s totally plausible that it would appear Custer had forsaken Reno’s command.”

At Little Bighorn College in Crow Agency, Tim McCleary, the head of General Studies, says of the book, “There wasn’t anything new or dramatic. The Curtis papers are valuable in that it is another perspective, and how people interpret the various interviews adds to the controversy surrounding the battle. What does set Curtis’s investigation apart is that it validated what were thought to be the points on the battlefield where the cavalry stopped.”

The highly regarded Crow reservation historian, Joseph Medicine Crow, states in Little Bighorn Remembered by Herman J. Viola that the Crow scouts’ testimonies were very similar, “but once the final action began, confusion quickly set in. Each scout saw things differently. White Man Runs Him, whose account has been regarded as the most reliable, stated: ‘I cannot remember every detail of the fight, because there were so many things happening during the day and so much excitement that it is hard to remember little things.’” Medicine Crow adds that White Man Runs Him, who is also his grandfather, “seems to have told two stories at one point.”

Doerner notes that acrimony existed among the scouts. In-depth study of the discord has diminished the certitude that Doerner and other scholars affix to the scouts’ narratives. He mentions Curley, a fourth Crow scout who also rode with Custer. From a distant bluff, Curley witnessed the final events unfold as Custer and his command fought their way to Last Stand Hill. That notoriety, and the distinction of being the first man, Indian or white, to disclose Custer’s defeat — to the crew aboard a steamboat traveling the Yellowstone River — brought him considerable fame and celebrity, which the other scouts deeply resented.

Other Little Bighorn survivors, both Indian and white, came forth with oral and written testimonies, some of which pictured the battle in a romantic light, a heroic fight against hopeless odds. Every account has deepened the debate over who should bear the blame for the 7th’s defeat. Even today scholars continue to amend their theories, shift blame, and offer new theories. One casualty has been Custer’s heroic image. His detractors concur with Edward Curtis’s belief that responsibility for the massacre rightfully belongs with Custer.

“People criticize George Custer for splitting the command and sacrificing Major Reno,” Doerner says, “but if the 7th Cavalry had struck the south end of the village en masse, the Indians at the opposite end of the village would have been free to escape. Standard tactics for attacking Plains Indian camps was to divide your force and strike the camp from several points at the same time. When the enemy is attacked from different points, he is forced to divide his forces.

“Again, you have to examine the battle’s complexities.”

Doerner mentions the personal narrative written by Major Reno in 1884. He contends that Reno “exonerates George Custer from what the Crow scouts and Curtis said, that Custer abandoned Major Reno and his soldiers.” To stress his point, Doerner cites these passages:

“I now believe I know why George Custer decided to attack the village from the opposite end and not support me as he originally intended, and that he actually supported me by trying to draw warriors away from me by striking the opposite end of the village.

“Our great mistake from the first was that we underestimated the strength of the Indians, and it was this alone which led to such disastrous results. I’m convinced that, had Custer known the great force of the Sioux he would never have divided his command.

“Even now after a lapse of nearly 10 years, the horror of Custer’s battlefield is still vividly before me, and the harrowing sight of those mutilated, decomposing bodies crowning the heights on which poor Custer fell will linger in my memory till death.”

The long held belief that Major Reno betrayed Custer tainted the remainder of his military career. A number of other troubles followed. He began to drink. He died friendless and broke in 1889.

Sadly, misfortune also befell his advocate, Edward S. Curtis. The North American Indian, which represented more than 30 years of Curtis’ intimate contact with North American Indians, was largely unprofitable. The undertaking cost him his marriage and health. By the time of his death in 1952, he was broke and his achievements virtually forgotten. Were he alive today, the lavish praise and historical value contemporary scholars have since bestowed upon The North American Indian would have likely eased his disappointment, given the ho-hum reception of The Papers of Edward S. Curtis Relating to Custer’s Last Battle.

- Watching for the Signal, photo by Edward Curtis, c.1908. Description by Edward S. Curtis: When there were indications that the war-party was near the enemy, a halt was made while the scouts reconnoitered the position of the hostile party.

No Comments