26 Aug Expressionism of Theodore Waddell

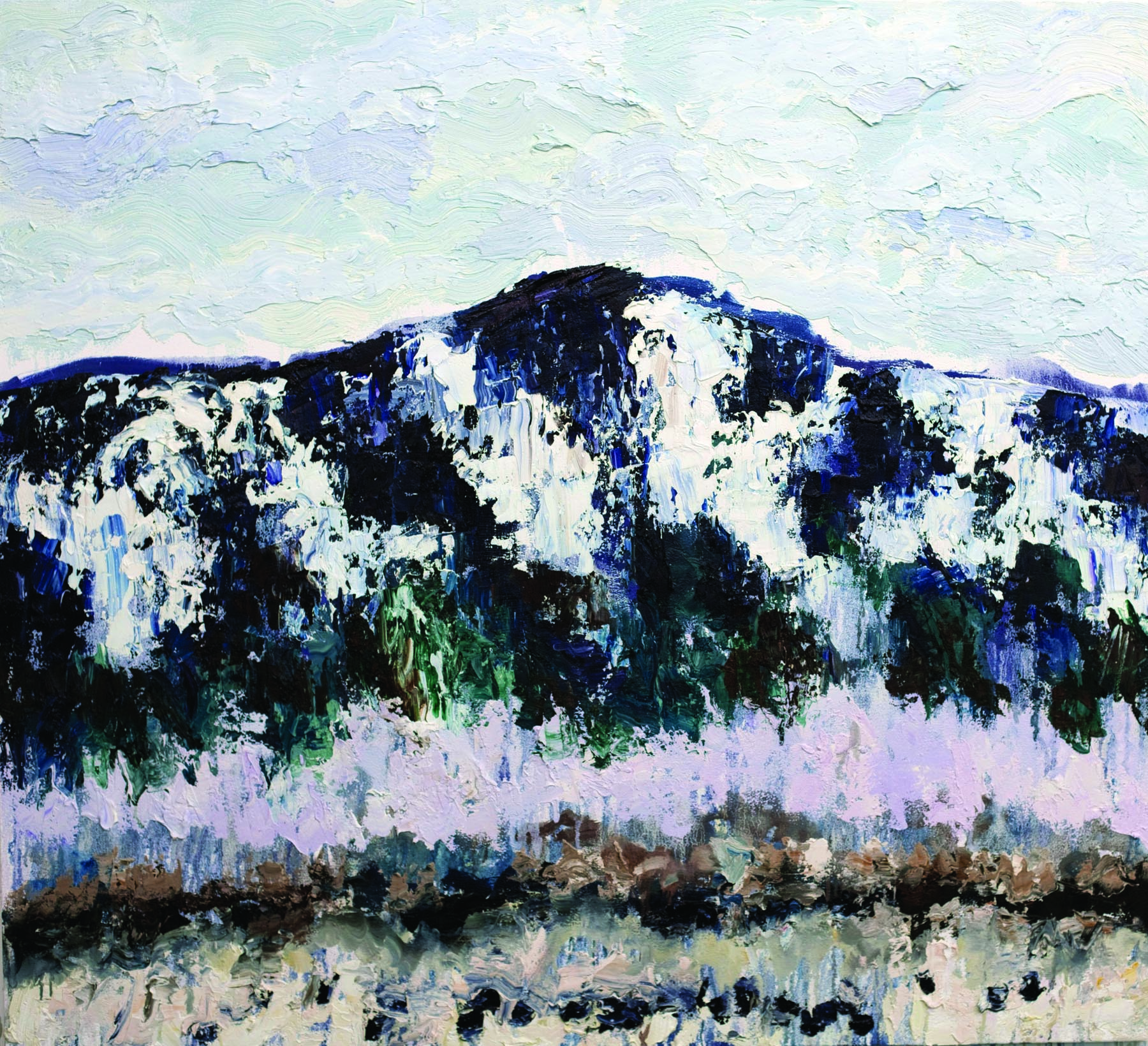

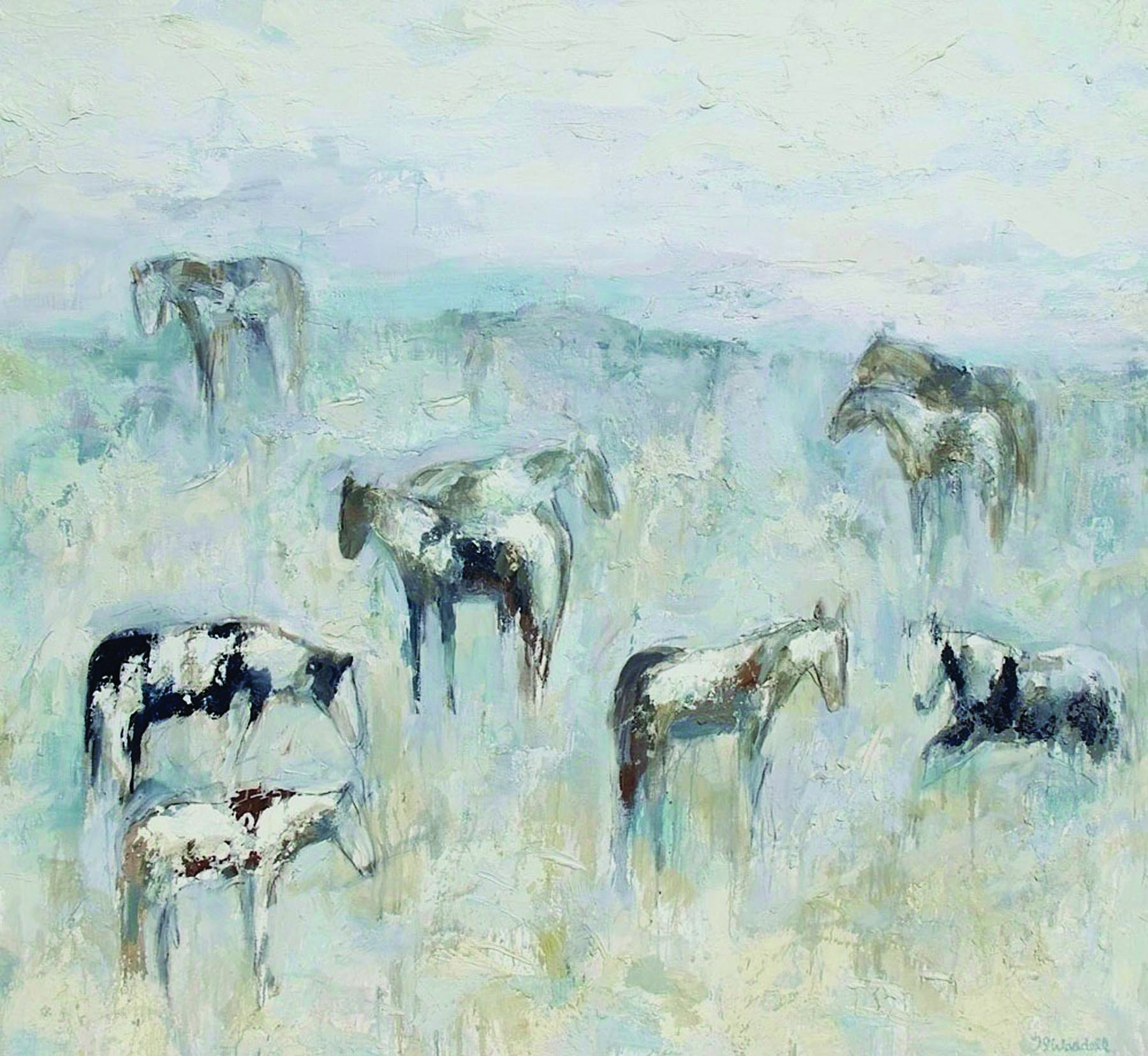

TED WADDELL BREATHES IN THE WORLD and exhales it in thick, thick paint. A swirl of colors lifted, swiped and spread. His paint, given to the canvas in wallops of bravery, is the water in clouds, the sunlight absorbed by grass. His images strike immediately at our hearts, which allows the subtle details to sink in later.

Working with the perspective of distance as well as an innate knowledge of the land and the big, big sky, Waddell’s paintings tell us everything we already know in a way we couldn’t foresee. His silhouettes of horses, cattle and sheep read in our minds like a familiar road, the scenes we pass when we drive and drive. The things we hardly notice: how the deep standing snow embeds itself in the reflected and muted light of a long winter.

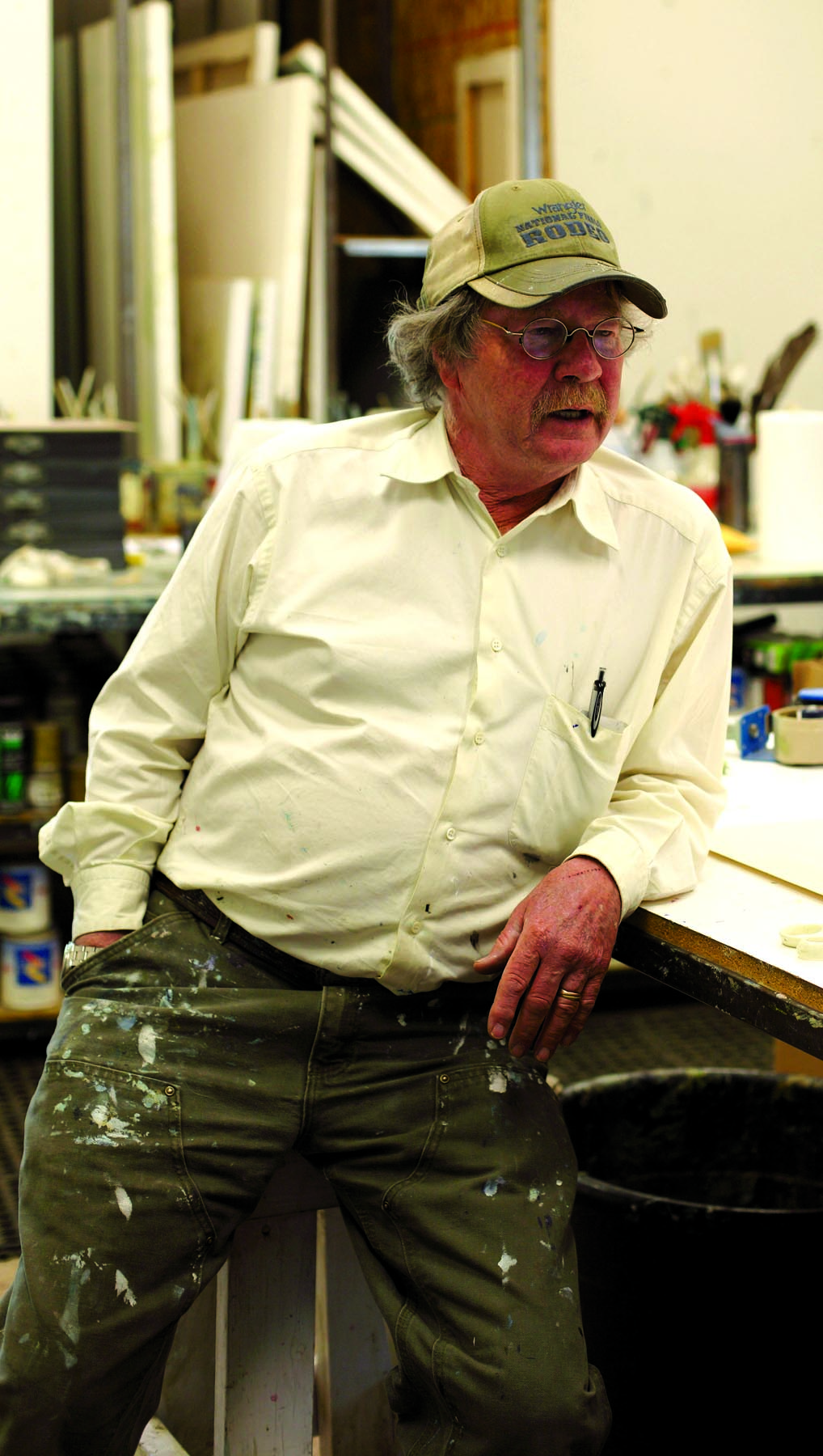

“For me, it’s what I see,” Waddell says, in his Hailey, Idaho, studio. “I can’t paint anything I can’t see.”

Open the door to his studio, a former riding arena, and turpentine fumes reach out with a handshake and a hug that says work goes on in here. Six canvases in various sizes hang in the back portion, the part dedicated to oil painting. Lots of paint and lots of painting. His palette, a long countertop mounded with white and blues, rows of brushes, and jars of the ever-present turpentine stand at the ready. There is even a spray bottle filled with turpentine.

“I work on whichever one,” he says. “Everything advances itself equally. And recently, I’ve felt that the paintings now demand more.”

In front of a just started painting, a diptych of the view at Monida Pass, he says, “I’ve been looking at this mountain for 20 years and I never get tired of it.” Waddell picks up a coarse-bristled brush, blue with turpentine-soaked paint. He presses the brush against the canvas adding a dripping swath of blue into the wash drawing. This is Waddell sketching. “From this view is one of the few places you can understand perspective. It’s palpable. A cow or a fence line will recede to a pencil mark.”

We know the cows are coming, in the way only Waddell can add them, with perspicacity. And then he says, “The cattle there are the toughest around. They winter without shelter — it’s brutal — but they survive.”

To get to the top of the painting, Waddell uses an inventory ladder. One of the many unintended art tools in his studio.

“I’m not sure what the relationship will be between the sky and the horizon,” he says, climbing the stairs. “I feel the sky will be layers. I do use photographs to remember the light but you have to trust your instinct. It’s all about bypassing your intellect and trusting your vision. We often intellectualize things — like the grass is green — but hell, no, the grass isn’t green.”

His work, now iconic of contemporary American Western painting, is collected by museums and owned privately and publicly across the globe. And despite this stardom, Waddell is extremely approachable, as are his paintings.

In his illustrious career, Waddell feels lucky to have succeeded. “I knock on wood a hundred times a day,” he says. “For the first 25 years nothing happened. Then I was chosen by the Corcoran Museum for the Biennial of American Painting.”

It was after that landmark show in Washington, D.C., that Waddell began to be taken seriously by the art world.

Gordon McConnell, painter and former museum curator, says Waddell emerged in national prominence in the early ’80s with the Biennial and the Western States Arts Federation who sponsored a survey of Western art.

“Ted just came up with something that was part of the zeitgeist,” McConnell says. “With his passionate paintings of the Angus cattle, starting with enamel house paint like Jackson Pollack, and black and white like [Franz] Kline. He made a huge impact. His work really stands the test of time with his peers of that period.”

McConnell has known Waddell for more than 30 years and appreciates the importance of his work.

“I understand the rarity of an artist doing something relevant, internationally, from a remote area like Montana,” McConnell says. “As a ‘Western’ painter, he has a deep romance with the West. Subject matter of the ranchlands with horses and cattle and mountain vistas is within the set of Western icons. The Western collections he’s in — like the Denver Art Museum or the Buffalo Bill Center of the West — he’s out on the left wing of the artists in those collections. But he bridges the regional subject matter with the international currents of Modern art.”

Brilliantly tying Abstract Expressionism with the Neo-figurative Expressionists, Waddell still works to find the newness in every painting.

“Ted had the good fortune, the skills and the perceptiveness to place his work in a sweet spot,” McConnell says. “He’s continued to evolve his own vision — as an observer of natural phenomena. He’s continued to make his mark and continued his work of historic value. He has work in a lot of significant collections. He completes the story of American art in a vibrant and inspiring way. Very few have gone to the abstract perspective that Ted has cultivated.”

In the studio, Waddell moves to another painting.

“A lot of my work has to do with the viscosity of the paint itself,” he says. “It depends on what the painting requires. I like them to stay wet, so I can manipulate the color.”

About 20 years ago Waddell was invited to Africa to paint the wildlife there. Unfortunately, his paints never made the trip, getting lost en route. Waddell was stranded without the luxury of his usual gads of oil paint.

“When my paint didn’t show up I was left with these little tubes of paint, the only thing available,” he says. “So I changed my technique and began using less and less paint on the canvas.”

But in the last few years he’s been drawn back to the abundantly luscious textures, colors and generous layering of his impasto work.

“The marks and the physicality of the paint is just not possible using less,” he says, picking up a masonry trowel and smoothing it over the sweep of paint. This alone creates a magnitude of depth that would be impossible if the paint were any thinner. Because of the characteristic of oil paint, the surface nearly shines, allowing any light to reflect off the plane in an almost bas-relief. “Nothing compares to oil paint.”

This work and many more to come will be included in two shows that will run through September. One will be with his daughter, Arin Waddell, at Visions West Gallery in Bozeman, August 8 through September 10. The other will be a solo show at Altamira Fine Art in Jackson, August 11 through 23.

Mark Tarrant, owner of Altamira Fine Art, is looking forward to seeing Waddell’s new work and feels Waddell is a noteworthy artist of our time.

“Waddell is the conduit from the regional art of the West to the contemporary and stands as one of the significant Western Modernists of the last four decades,” Tarrant says. “He is considered an Abstract painter by some and by others an Expressionist. I see the influence of the Monet Water Lilies series, the artist exploring his muse; for Waddell … the influences become the pastures and mountains of his life in the West.”

Waddell’s landscapes embody the spirit of living in the West, more than that, the animals on which we tend and depend, the weather where we are often tossed and turned, in essence the spectrum of contemporary life imbued with wide open spaces. And yet, he doesn’t let us forget that we are looking at paint, at his version of place. Not just looking, but transporting us.

At his work table, Waddell loads up a dollop of blue with a healthy helping of white onto a large, round-bristled brush; it’s actually one-third of an asphalt applicator brush.

“I’m convinced that what I learned from John Singer Sargent is that he loaded his brush with two colors, so I’m loading my brush with two colors,” he says, and slides his brush across the sky of a painting. The direct contact with two colors onto the canvas leaves grooves from the bristles and precise lines that would be hard to accomplish with individual strokes. “I’m learning every day.”

- “Monet’s Sheep” | Oil | 70″ x 120″

- “Beaverhead Angus #14″ | Oil | 54″ x 60”

- “Stillwater Horses #3″ | Oil | 54″ x 60”

- “Deer Creek Bull #2″ | Oil | 42″ x 48”

- The artist, Ted Waddell, in his Hailey, ID, studio.

- “Madison Horses #3″ | Oil | 72″ x 78”

- “Winter Angus” | Oil | 72″ x 72″

No Comments