30 Jan Excursion: Road Tripping

I wound across western Wyoming’s isolated Bighorn Basin in my indefatigable 1977 Chinook micro-camper, 260,000 happy miles under the Toyota’s hood. Summer heat waves shimmered and danced like Sahara mirages over the arid landscape. Miles away, a truck pulling a horse trailer into the backcountry was stirring up dust devils. Enormous, purple cumulus clouds hung threateningly over distant Bighorn Mountain peaks, like the face of a bruised boxer, ready to go down hard.

The East Fork of the Wind River near Dubois, Wyoming is a haven for Yellowstone cutthroat trout, which are native to the Bighorn Basin’s watershed. Running from the south slope of the Absarokas, the moderately sized stream offers excellent public access in the state’s Spence & Moriarity Wildlife Management Area. To the south is the Wind River’s main stem and spectacular namesake mountains, with constellations of excellent fly-fishing options.

The clouds suggested sonic-boom thunder, hit-and-miss lightning strikes, and torrential rain squalls somewhere in the oceanic expanse. Athletic pronghorns sprinted away like Porsches, a golden eagle glided on updrafts, and a coyote family slunk into the sagebrush. Deeply incised badlands erupted in tan and ochre, displaying sensuous bends, folds, and shadows, like photographer Edward Weston’s California nudes. Unseen, the relentless erosion slowly revealed fossilized dinosaurs that roamed the earth millions of years ago.

As desiccated and forbidding as parts of the basin appear, it’s the epicenter of a trout paradise, offering some of the West’s finest, idiosyncratic fly fishing. The secret lay on the horizon — to all cardinal points — where mighty mountain ranges rim the valley: the Bighorns looming to the east, the Absarokas soaring on the west, the Pryor escarpment hugging the Montana border to the north, and the Owl Creek Mountains lurking on the southern edge. Summer snowmelt from these ranges — rising to 13,167-foot Cloud Peak in the Bighorns — feeds excellent trout streams like the Wind, Shoshone, and Greybull rivers, along with Medicine Lodge and Paint Rock creeks and other sister waters slicing through deep canyons to the Bighorn River, which threads through this beautiful depression on its long journey to Montana’s Yellowstone.

The remote country along the basin’s periphery exerts a powerful magnetic pull for fly anglers. It’s big, rugged, sometimes dangerous territory that might leave scars with great memories, adjusting your perceived place in the natural hierarchy. Fresh grizzly bear tracks in riverside mud near my camp one morning on the Shoshone did that for me — an adrenaline spike accelerating the morning coffee rush — with more surprises down the road.

Wyoming’s Wind Transforms into the Bighorn

I love the diverse, sometimes parched landscapes of the Cowboy State. Like a head-on collision between Montana and Nevada, there’s a fierce beauty to the place and a scattered population of tough, independent people that’s unsurpassed. On a planet inhabited by 8 billion humans, it’s stunning to travel through sprawling country that remains largely uninhabited and undeveloped, America’s least populated state. That’s one reason wild, indigenous trout still remain.

Indigenous Yellowstone cutthroat trout have lost much of their territory in the Bighorn Basin — and elsewhere in the Northern Rockies — due to exotics and other environmental factors, but they still persist heartily in upper reaches and tributaries.

Butter-bellied Yellowstone cutthroats are the native Bighorn Basin trout, historically roaming deep into the Wind River headwaters. During the past century, brook, brown, rainbow, and even lake trout were introduced into the drainage; these exotics thrived, appropriating much of the water. Opportunistic, eagerly rising Yellowstone cutts endure mainly in remote freestone tributaries, and there are few better places than the pristine upper Wind drainage.

One thing I observed about Bighorn Basin cutts was that they were capable of inhaling large attractors with such teasing subtlety that I often didn’t realize I had a strike until I accidentally felt them. Stay alert or you’ll miss many good fish, like I did while daydreaming amid the spectacular scenery. Also, on some patterns, I had many false hits, nice cutts rising from the depths only to nose the bug, then retreat infuriatingly to the bottom. Keep experimenting with different sizes and configurations until you’re getting solid hits.

Along with the Snake, Green, and North Platte, the Wind River ranks among Wyoming’s marquee trout streams. It also has a Janus-like name, magically morphing into the Bighorn River in the productive canyon tailwater between Boysen (Reservoir) State Park and Thermopolis at the so-called “Wedding of the Waters.” As it works downstream collecting the Bighorn Basin’s water, it gradually becomes a warm, silty, high-desert stream better suited to whiskered catfish than sleek trout. Further downstream, however, it changes character again, into another exceptional trout tailwater below Montana’s Yellowtail Dam.

After working a meaty attractor pattern on an East Fork Wind River run, a beautiful 18-inch Yellowstone cutt was soon caught and released.

In the Wind’s upper reaches, the best water runs down to about Riverton; this stretch meanders through the Wind River Indian Reservation, where anglers need to purchase a tribal permit. Above the reservation, there is scattered public access running up through Dubois, above which the more intimate Wind descends from lofty terrain in the Bridger-Teton National Forest, near 9,658-foot-high Togwotee Pass.

The Wind has deep cultural ties with the Eastern Shoshone, Northern Arapaho, Cheyenne, Crow, and Gros Ventre tribes (the first two share the Wind River Reservation). The tribes skirmished for regional control, and a significant geological feature in the drainage was named after one altercation. According to David Lageson and Darwin Spearing (Roadside Geology of Wyoming), the legend is this:

Chief Washakie led the Shoshone … against the Crow Indians, led by Chief Big Robber. In an effort to save lives, Chief Washakie suggested that he and Chief Big Robber fight alone at the top of this butte — the winner would eat the other’s heart! Washakie won and the butte was named “Crow Heart.” In his old age, Washakie was asked if he actually ate Big Robber’s heart; he replied “youth does foolish things.”

I’ll vouch for that last line: Though my youth is as long gone as Big Robber’s heart, for better or worse, foolishness didn’t vanish with it.

Prospecting for Greybull Cutts

Before journeying up the grizzly-populated Greybull in search of sizeable cutthroats — while enjoying a beer and locally raised bison burger in Meeteetse’s iconic Cowboy Bar — I read with alarm in the Cody Enterprise about two Wyoming hikers and hunters killed by grizzlies. As summer slides into fall, basin rivers like the Greybull are corridors channeling bruins down from the mountains to lower-elevation pre- hibernation feasting grounds, which are often adjacent to prime fishing areas. Bear awareness, then, is crucial.

The upper Greybull River cascades out of the wild, rugged Absaroka Range. The long, winding gravel road out of Meeteetse ends at the edge of wilderness in the Shoshone National Forest, at the Jack Creek Campground. A long trail takes fly anglers into Yellowstone cutthroat and grizzly paradise.

Meeteetse is among the oldest Bighorn Basin settlements, dating to the 1870s. It couldn’t get more Wild West if Buffalo Bill himself rose from the dead and rode in on horseback. The town sits between Cody and Thermopolis, on lonely State Highway 120, along the rugged transition between high desert plains and the eastern front of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. This is untamed country, home to black bears, bighorn sheep, elk, moose, prolific pronghorn, and the mighty kings and queens of the mountains: grizzlies.

The 90-mile-long Greybull River is rooted in Indigenous legend: Tribes named the river after a rare albino bison bull that once roamed the area. On a cliff near the town of Greybull is a pictograph of a bison with an arrow in his body. With this picture goes the story that the old bull was finally killed by humans, who drove it over the edge of the bluff into the river below, which remains among the best refuges for Yellowstone cutts outside of Yellowstone National Park.

Below the Shoshone National Forest, the Greybull snakes through state land and sprawling ranches. This reach is renowned among biologists: The planet’s last remaining black-footed ferrets were discovered here in 1981 after they were believed to be extinct. A roving range dog named Shep presented his owners with a weasel-like animal he discovered on the historic Pitchfork Ranch. The ferret was turned over to wildlife officials, who located a colony that was later used for breeding restoration efforts, rescuing them from oblivion. Because of the exceptional natural resources in the Greybull watershed, organizations like The Nature Conservancy and the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation have cooperated with ranchers on conservation easements and habitat improvement along the river.

An important Greybull tributary — the Wood River — also offers fine fly angling, camping, and exploring. Part of the drainage includes the Sunshine Reservoirs, affording stillwater action for portly trout. On the Wood and Greybull — as with much of the basin’s water — attractors, terrestrials, and garish Liberace-like foam hybrids work well, mixed with standard western hatches like Blue-Winged Olives, Pale Morning Duns, Drakes, Tricos, Yellow Sallies, Golden Stoneflies, and caddis and midge species.

There are interesting cultural remnants, too, in the Wood’s drainage, tucked below pyramid peaks. Sojourners find streamside campgrounds and trailheads on the way up; the road eventually turns into a jeep track and follows the Wood past the historic Double D Dude Ranch to the ghostly gold-mining hamlet of Kirwin, perched at 9,500 feet.

And high in the headwaters rest the lonely, unfinished remnants of pioneering aviator Amelia Earhart’s planned retirement cabin, a refuge she never enjoyed after her plane mysteriously disappeared over the Pacific in 1937. That’s the way it is in the Greybull region: You feel like you’re venturing beyond terra firma into the unknown territory, where ancient cartographers decorated their map edges with fierce, mythological beasts.

Exploring the Bighorns’ Rugged West Slope Canyons

A rise dimpled a sweet Medicine Lodge Creek run; a second and third drew my rapt attention. Cat-like, I crept into position below a large log, delicately dropping a size-18 foam beetle with my four-weight. A rise, a miss, then another. Finally, a solid take, powerful head shakes, and a 19-inch brown exploded out of the water. Straining the 5X tippet, I muscled the rodeo bronc trout out from under its timber home several times and optimistically searched for a landing beach when the fly slipped out. Depressed, I watched the fish rest in plain view before it disappeared back under the log.

The author works a cliff-side run for brown trout in Medicine Lodge Creek.

What was extraordinary wasn’t necessarily me haplessly losing another linebacker-shaped fish — a common occurrence — but accomplishing that in a popular state park near my campsite, on a stream an elderly, three-legged ranch dog might easily jump across in places. The limestone chemistry of Medicine Lodge Creek produces prolific, pugnacious browns.

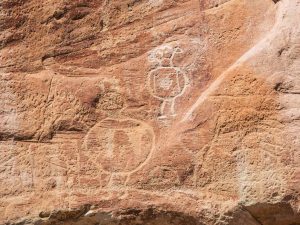

Medicine Lodge State Archeological Site offers superb fly fishing, but is also one of Wyoming’s best outdoor museums of petroglyphs and pictographs. Archeologists concluded the site was inhabited continuously for 10,000 years: Excavations went down 26 vertical feet through 60 cultural levels, uncovering grinding stones, projectile points, and other artifacts.

Here, Indigenous people found everything they needed to thrive, including abundant big game, a diversity of life- sustaining plants in four different vegetation zones, plenty of fresh water and fish, and cave shelters under heat-reflecting sandstone cliffs. Former Wyoming State Archaeologist and anthropology professor George Frisson — who spearheaded digs here beginning in 1969 — called it the “oasis of the Bighorn Basin.” In his book, Prehistoric Hunters of the High Plains, Frisson observed that “The Medicine Lodge Creek site is probably the most complex campsite known in the Northwestern Plains.”

Some of Wyoming’s finest petroglyphs and pictographs are protected at Medicine Lodge State Archeological Site. The bountiful landscape on the west slope of the Bighorn Mountains has supported human occupation for 10,000 years.

Medicine Lodge is only one of the archaeological, geological, and piscatorial gems in the breathtaking canyons ripping through the Bighorns. Nearby, Paint Rock Creek cascades through a trout-populated chasm accessible to hikers, backpackers, and equestrians. To the north, Shell Creek slithers along U.S. Highway 14 through a magnificent canyon riddled with rapids, waterfalls, and dramatic walls. On the south side, the other major route over the Bighorns — U.S. 16 — follows Tensleep Creek into the heart of the great range. And then there’s a sleeper: diminutive Canyon Creek in The Nature Conservancy’s Tensleep Preserve, where permission is required to fish.

Wild Mountain Adventures and Mishaps

Hiking back to my remote South Fork camp after fortuitous, bruin-free fishing on the Shoshone, I spotted an incredible sight at the nearby Boulder Basin trailhead, sending a dreadful chill down my spine: flashing red ambulance lights, bustling emergency personnel, and a just-landed helicopter, blades twirling. I instantly thought, someone just got mauled by a grizzly. I hiked to the chopper to assess the situation: The EMTs had received a report of an injured elk hunter above 9,000 feet but didn’t know the details. They were letting the high winds abate, preparing for an emergency rescue in an area punctuated by 2-mile-high peaks. I watched the whirlybird lift off, darting dragonfly-like over rocky ridges and canyons, disappearing into the wilderness.

An hour later, I heard the ’copter again, a speck threading the high peaks. As it came into focus, I saw the wounded bow hunter dangling precariously from a 50-foot rope, getting the ride of his life. The terrain was too rugged to land, so they harnessed him in while the helicopter hovered above. The expertly piloted aircraft gradually descended, safely and precisely lowering the victim into the back of the waiting ambulance.

A Yellowstone cutthroat trout rests in the net after a hard fight, ready for a well-earned release.

It turned out I unfairly blamed a grizzly for the accident. The hunter was bucked off his horse and fractured his ribs in the process. But that’s the way it goes in and around the spectacular Bighorn Basin: Offsetting the high rewards of venturing into one of the wildest landscapes in the country comes risk, which, when adequately assessed, is generally worth taking. As Edward Abbey penned in Desert Solitaire, “May your trails be crooked, winding, lonesome, dangerous, leading to the most amazing view. May your mountains rise into and above the clouds. May your rivers flow without end …” Testimony and testament: Ultimately, it’s what I live for; perhaps you, too.

Bighorn Basin Towns, Culture, and Bars

While sparsely populated, there are interesting Bighorn Basin towns beckoning anglers needing supplies, a room and a shower, or a tasty meal not cooked over the campfire or Coleman stove. It’s also a landscape where giants roamed: wise Shoshone Chief Washakie; crafty Butch Cassidy of outlaw fame; and the renowned showman, entrepreneur, and hunter Buffalo Bill Cody, whose namesake town is the basin’s cultural center.

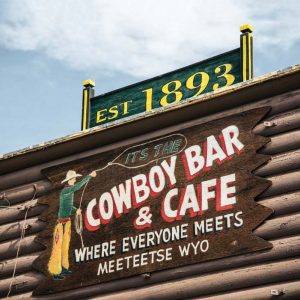

The venerable Cowboy Bar & Café has anchored downtown Meeteetse for more than a century. Study the walls and ceiling for historic bullet holes.

Starting at the south end and moving clockwise around the basin, significant towns include Thermopolis, Meeteetse, Cody, Powell, Lovell, Greybull, and Worland. From a traveler’s perspective, Cody offers much, including fly shops and diverse restaurants and lodging. It also hosts one of the best cultural attractions in the Rockies — the Buffalo Bill Center of the West — with five separate venues under one roof: the Buffalo Bill Museum, Whitney Western Art Museum, Plains Indian Museum, Cody Firearms Museum, and Draper Natural History Museum. Another popular downtown draw is the historic Irma Hotel — with an iconic bar and restaurant — founded by Buffalo Bill in 1903 and christened after his daughter.

Surrounding villages have their own magic. Meeteetse — gateway to the upper Greybull — offers one of Wyoming’s historic watering holes, the venerable Cowboy Bar. The town’s name, after all, is derived from a Shoshone word for “meeting place.” Bandit Butch Cassidy was arrested here in 1892 for stealing a horse worth $5, rather than for other malfeasance like robbing banks and trains. He was sentenced to two years in the Laramie State Penitentiary, the only jail time of his lengthy, exceptional criminal career.

Cody’s Buffalo Bill Center of the West ranks among the best, most diverse museums of Rocky Mountain history, culture, and science in the region.

Adding to Meeteetse’s mystique, one of America’s most wanted murderers — a violent Arizona prison escapee named Tracy Province — drifted through in 2010, making new friends at the Cowboy, singing in the church choir, and trying to blend into the community before being recognized, handcuffed, and returned to prison. On an earlier trip, I just missed crossing paths with this upstanding citizen. A bartender who served the killer told me she hadn’t recognized him from TV mugshots because “they didn’t show the tattoos and missing teeth.” She added, “Meeteetse is such a welcoming community that people just took him in.”

The Irma Hotel was founded by Buffalo Bill Cody in 1903 and christened after his daughter in the town named after him. The venue includes a restaurant and bar, sometimes featuring live music.

For anglers visiting Paint Rock or Medicine Lodge creeks, the hamlet of Hyattville is the place to score a beer, juicy burger, and ice for the road. The Paint Rock Inn offers all these, too, amid classic rural Wyoming bar decor. For a change of venue — and an opportunity to visit with local ranchers — try the Hyattville Bar & Grill next door.

And, if your casting arm is sore from fighting jumbo-sized browns and rainbows in the Wind and Bighorn rivers, Thermopolis is what the sagacious doctor ordered. The town is renowned for its sybaritic hot springs — among the world’s largest — with a retro Disneyland-like vibe. If you rise early enough, you can catch the Trico hatch levitating smoke-like over the Bighorn in the center of town.

Jeff Erickson has logged thousands of road miles and 16 years as an environmental, land use, and outdoor recreation planner in Montana and Minnesota. In addition, his stories and photographs have been published in Montana Outdoors, Fly Fisherman, Fly Rod & Reel, and many other publications.

No Comments