29 May Excursion: Idaho’s Kelly Creek

Hardcore cutthroat bums roaming Western backroads with their fly rods, waders, and extra gas tanks know the marquee water, like teenagers with nose rings and spiky hair eagerly touting their favorite punk bands. Vagabonds chasing westslope cutts often head for Montana’s upper Flathead, Clark Fork, and Blackfoot systems; Idaho’s crystalline Lochsa, Selway, St. Joe, Middle Fork of the Salmon, and North Fork of the Clearwater; and the latter’s legendary, exquisite tributary, Kelly Creek. As Chris Hunt underscores in his book, Fly Fishing Idaho’s Secret Waters:

… all the rivers and streams that come together to form the Clearwater have a fishy legacy that rivals that of any stream system. … The fishing for native westslope cutthroat trout in the North Fork and its tributaries is probably the best in the state and maybe the West.

Tucked in Idaho’s panhandle, Kelly Creek has long been magnetic for intrepid cutt-cultists from across the country. Anglers don’t just drift in on a whim to the wild, sunset-side of the Bitterroot Mountains that serrate Idaho and Montana. It takes a dashboard of cartography, coolers full of food and beverages, and a love for labyrinthine, gravel roads.

Roaming a Primitive, Previously Scorched Landscape

After a long drive, my wife, Mary, and I pulled into our isolated cutthroat headquarters, Idaho’s Kelly Forks Forest Service campground, arriving late in the afternoon and securing one of the few remaining campsites. The next morning, early-rising Mary did a fresh campground reconnaissance and discovered the best streamside site had just been vacated. She dropped some gear on the picnic table, raced back to our site, and rousted me out of my cozy sleeping bag: “Dude, get up! You won’t believe the campsite I just scored.”

Large boulders in Kelly Creek provide excellent cover for westslopes and ideal viewing or casting platforms for ambitious fly anglers. | PHOTO BY JEFF ERICKSON

We quickly registered for the new site, moved, and settled in for five wonderful days. From our perfect spot, Mary and I admired Kelly from our firepit and picnic table, a short hike from a deep, clear run. On warm afternoons, we relaxed in a boulder-lined bathing pool, no doubt laboriously constructed by beaver-like kids. When cutts were hunkered down under the heat and high sun, we read and watched birds and butterflies sail past in a spectacular setting framed by fir, cedar, spruce, and distant mountain silhouettes.

A school of cutthroats sways gracefully in Kelly Creek’s clear, sometimes aquamarine current. The fish often migrate upstream during spring spawning season and downstream, later, to find deep, secure wintering water. | PAT CLAYTON/FISH EYE GUY PHOTOGRAPHY

Today’s calm splendor disguises previous devastation. The Kelly Creek and North Fork watersheds were incinerated by the 1910 Big Burn, one of the worst forest fires in U.S. history, with sky-scraper high walls of flames dozens of miles wide. Extreme aridity, searing heat, thunderous lightning strikes, and tornadic winds ignited a monstrous inferno that scorched 3.2 million acres in Idaho, Montana, and Washington, killing more than 70 firefighters. Regional towns were cremated, as were vital railroad trestles, hindering evacuation.

Timothy Egan’s 2010 title, The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire that Saved America, details desperate forest rangers reporting an apocalypse to Washington, D.C., supervisors, foreshadowing the disastrous blazes raging today with increasing frequency across the West, due, in part, to climate change. In Egan’s words:

They wrote of giant blowtorches flaming from treetop to treetop, of house-size fireballs rolling through canyons, pushed by winds of 70 miles an hour. They told of trees swelling, sweating hot sap, and then exploding; of horses dying in seconds; of small creeks boiling, full of dead trout, their white bellies up; of bear cubs clinging to flaming trees, wailing like children.

Westslopes share Kelly Creek with native bull trout — the apex stream predator — that can attain impressive sizes, sometimes by devouring cutthroats. All bull trout must be released. | PHOTO BY JEFF ERICKSON

Depending on where a drop of rain falls on the nearby, revegetated, wildlife-rich Bitterroot Divide, it either flows west into Kelly Creek and the North Fork of the Clearwater River or east into Montana’s Clark Fork River drainage. The Kelly headwaters split into three forks and tiny mountain creeks in the Clearwater National Forest, punctuated by scattered alpine lakes, mostly accessible by hiking, horseback, and off-highway vehicle trails or cross-country bushwhacking.

Pristine Cutthroat Habitat Haunted by Phantoms

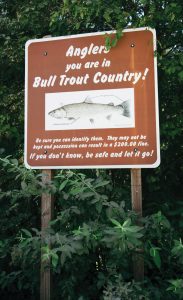

In addition to westslopes, indigenous Kelly Creek salmonids include mountain whitefish and threatened bull trout, which must be released if caught. While cutts are the main draw, non-native brook and rainbow trout also inhabit the North Fork watershed.

Kelly and the North Fork historically produced prodigious chinook salmon and steelhead runs, with fish weighing more than 20 pounds. Unfortunately, the salmon and steelhead migrations up the Snake River from the Pacific Ocean ended when Dworshak Dam was constructed on the North Fork between 1966 and 1973. The massive 717-foot-high barrier was built without a fish ladder, an environmental disaster that severely altered the watershed’s ecology. Post-spawn chinooks added important nutrients to the system — the fish provided meals for hungry bears and other wildlife, their eggs supplied food for trout. Poignantly, the last chinook and steelhead smolts drifted downstream through the construction site in 1970, never returning to their ancestral spawning grounds.

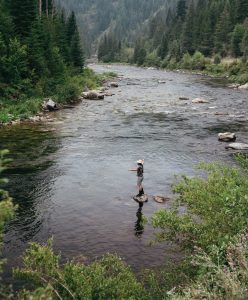

A fly angler works an enticing reach of Kelly Creek. The stream offers a diversity of riffles, runs, rapids, and pools, with plenty of access on public land in the Clearwater National Forest. For many campers, Kelly Forks campground is headquarters. | PHOTO BY JEFF ERICKSON

My former work colleague at Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks, Bob Walker, conducted snorkeling surveys on Kelly Creek and the North Fork while he was a fisheries biology graduate student at the University of Idaho in the early 1970s. Part of his research was to establish baseline data about the pre-dam aquatic ecosystem. “Everyone knew what impact [the dam] would have,” he says, referring to the future loss of salmon and steelhead.

Walker wore a wetsuit while snorkeling 10 miles downstream through rapids and runs, and some of the deepest, albeit transparent, holes “were almost spooky.” Part of his work was counting cutthroats he spotted while swimming, tallying them in his mind while he floated, and reporting what he observed later. “It’s a beautiful river that opens up with views,” he says. “You know you’re in wild country.”

Generally, westslope cutts maintain a tenacious, though reduced, hold in their native waters west of the Continental Divide, including Idaho, where they have endured since the last Ice Age. The name “westslope” is somewhat misleading, as they reside on both sides of the Continental Divide. According to noted late fisheries biologist Robert Behnke, westslopes were originally the most abundant and widely distributed of the cutthroat subspecies. Their main territory included northern Idaho, western and central Montana, the Gallatin and Madison headwaters around Yellowstone National Park, and southern Alberta and British Columbia. Additionally, isolated populations persist further west along the east slope of Washington’s Cascade Range and in the John Day basin in central Oregon.

When Lewis and Clark first scientifically identified (then eagerly devoured) 16- to 23-inch westslopes below the Great Falls of Montana’s Missouri River in 1805, the trout were prolific and widespread in the watershed, cohabitating with mountain whitefish and Arctic grayling. Genetically pure westslopes eventually dropped to under 5 percent of their original habitat in the Upper Missouri River Basin, although Montana has aggressively worked to improve their situation — mainly in headwaters — with notable successes. Reasons for westslope reductions on both sides of the Divide are multifaceted, including competition from non-native trout species, overharvest, and habitat destruction from logging, agriculture, roads, mining, and development.

West of the Divide, westslopes have been better able to move and intermingle more freely through large river systems like the Kelly Creek/North Fork complex, Dworshak Dam notwithstanding. This has helped them fight challenges that have more severely reduced their populations elsewhere. Additionally, and partly based on Walker’s survey research, cutt catch-and-release regulations were instituted on Kelly in 1970 — well before such rules were widespread — substantially increasing both the number and size of trout, which had suffered from overharvest. The special regulations also mandate barbless hooks and prohibit bait fishing. Because cutts have a reputation for feeding aggressively and being more gullible than browns and rainbows, these restrictions have helped Kelly’s robust westslope population.

Maximizing the Prime Fishing Window

Premier showtime on Kelly is July through September to avoid a tsunami of spring mountain runoff, slippery roads, and the early sharp bite of winter. Further down on the North Fork, the dangerous early-season torrents sometimes exceed 12,000 cubic feet per second (CFS). Even at summer flows under 1,000 CFS, the North Fork remains a fast, brawling river in places, threading through canyons with giant boulders and massive log jams, punctuated by transparent runs and pools — excellent cutthroat habitat.

A westslope cutthroat surfaces to inhale an insect. These trout can rise aggressively but sometimes have a sly, teasing manner: They will slowly follow and inspect your fly, then contemptuously bump it with their snouts before sinking back down to their lair. | PAT CLAYTON/FISH EYE GUY PHOTOGRAPHY

Many Kelly cutthroats migrate downstream toward the North Fork and Dworshak in September or even late August to winter in deeper, more secure water. The closer to autumn, the fewer westslopes remain, although September is otherwise tough to beat: The sizable, fluttering orange-bellied October caddis are trout candy, drawing cutts up to slash the surface amid flaming fall colors. The fish return to the headwaters for the spring spawning ritual, but angling is limited until the water recedes.

A typical Kelly cutt is about a foot long, although 20-inch trout are possible, with protected bulls running even larger. Cutts generally won’t retain prime residence in riffles or whitewater, where you might prospect for rainbows. Probe massive boulders, slick runs, cavernous pools, current seams, eddies, log jams, and willow-lined undercut banks. If you hit the jackpot, Kelly cutts consistently rise to the mirror surface like graceful, famished ballerinas, but sometimes drift back with the current, studiously examining your offering. If you’re lucky, skilled, or both, they’ll flash the white inside of their mouths as if slyly, tauntingly grinning at you. Just don’t make the mistake of striking too quickly — which I often do — before the trout has definitively inhaled your bug.

The North Fork of the Clearwater rumbles through its canyon, upstream from the junction with Kelly Creek. Like Kelly, the North Fork rises on the west slope of the Bitterroot Mountains, near the Montana border. The river offers excellent camping, fishing, and exploratory options. | PHOTO BY JEFF ERICKSON

Due to its relatively modest size and boulder-filled chutes, Kelly Creek is mainly wade-fishing water, although kayaks work in some reaches at the right flows. The North Fork of the Clearwater is big enough for rafts and boats, if you can competently work the oars through challenging cascades. An 8.5- to 9-foot 5-weight stick usually hits the sweet spot, although lighter wands or tenkara rigs are magic on the tributaries. During summer’s heat, focus on mornings and evenings, as the cutts sulk on the bottom or ascend cooler tributaries for more comfortable water.

In their comprehensive book, Flyfisher’s Guide to Idaho, Ken Retallic and Rocky Barker evocatively describe the Kelly experience:

Almost as pure as rainwater, Kelly Creek flows like liquid glass on its serpentine westerly course. … Looking into one of the deep pools below a galloping rapid is like gazing into an emerald aquarium. The water is so translucent that trout lazily finning in the subtle current appear to be suspended in mid-air. If you are lucky, you will watch with suspended breath as a “tanker” rises to your fly.

Ripple in Still Waters, the Road Goes on Forever

Backroad sojourners inevitably confront the good and bad. If both don’t occur, it’s probably not much of a road trip. One morning on the North Fork, just upstream from Kelly Forks, Mary maneuvered to a mid-stream boulder, casting into a sweet run. Getting off, she slipped hard and busted the tip off her vintage, mid-1990s-era Sage RPL+ 9-foot 5-weight — the fast-action graphite rod I have long coveted — perhaps my favorite in our large rod quiver. Fortunately, Mary was fine, and Sage surprisingly still had replacement RPL+ rod tips.

Later, we drove to the road’s end at the Kelly Creek Trailhead. Mary rigged up her backup tenkara rod; I hiked upstream to work some late-morning mayfly risers. Once satiated, I headed back and was confronted by a joyful scene: Mary was surrounded by a friendly herd of pack goats — including bearded billies sporting large, saber-like horns — while they enjoyed gentle petting, curious sniffing, and pack nipping. Their equally gregarious owner said he was getting ready to load them up and venture into the roadless Kelly Creek headwaters.

While sipping Scotch and reading around our last Kelly campfire, I contrasted our peaceful, Edenic setting with Egan’s description of the deadly maelstrom that enveloped the landscape in 1910:

After racing through the Clearwater and Nez Perce forests, leveling nearly all living things in the Kelly Creek region, the fire swept up trees at the highest elevations. At this altitude, along the spine of the Bitterroots, the wind moved without obstruction, and the fire itself threw brands 10 miles or more ahead of the flame front.

At one of our previous campsites, a generous earlier visitor had left a pile of finished books for us under the picnic table. One of them was the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of nuclear physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, American Prometheus. Reading about the Big Burn, I was reminded of Oppenheimer’s reflection on his work developing the first atomic bomb, taken from the sacred, ancient Hindu text, the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds.”

I also pondered the vanished salmon and steelhead that once pulsed past our campsite on primeval spawning runs. But, like a contented cat, Kelly Creek still purred reassuringly beneath the Milky Way. All felt reasonably right, optimistic, and resurgent amid the creative destruction and resurrection of a constantly changing world. For the first time since 1946, long-lost grizzly bears have reappeared in the region. And one day, Dworshak Dam will disappear by human or natural forces. Kelly Creek and the North Fork are case studies on how catastrophic environmental damage can heal, given time and tender care.

Reluctant to leave our Kelly Creek paradise, Mary and I finally broke camp and headed home to Helena, Montana. We wound our way up the increasingly intimate North Fork, listening to Grateful Dead and Robert Earl Keen songs, toward Hoodoo Pass. After nervously negotiating a landslide that nearly blocked the road, I briefly resumed my road-trip bliss at the wheel of our truck. Then, Mary suddenly shouted, “Dude, watch it!” I pumped the brakes as a large wolf crossed the road, then disappeared, ghostlike, into the dark forest, perhaps off to visit the mythical Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother. Primitive country like the North Fork begets large wild animals, some well endowed with teeth and claws.

Like the jewel-like cutthroats we played with and the luminescent, hovering hummingbirds at Kelly Forks, the wolf embodied the wild country we were fortunate to enjoy, another world away from the crazy, kinetic, hyper-wired 21st century. As we crested the North Fork headwaters and Hoodoo — painted with swaying, Monet-like impressionistic wildflowers — I reflected on lines from “Ripple,” an old Dead song, the perfect coda for a great trip:

There is a road, no simple highway

between the dawn and the dark of night.

And if you go no one may follow,

that path is for your steps alone.

Ripple in still water,

when there is no pebble tossed,

nor wind to blow.

Navigating Kelly Creek and the North Fork

Kelly Forks is the watershed’s one developed campground, although the nearby North Fork of the Clearwater offers other tempting options with plenty of public water. An advantage of camping at the Forks is that you can easily hike to both Kelly and the larger North Fork, which has many angling angles. It’s a pleasant place to camp, and if you’re settled in for a while, the adjacent ranger station also sells ice — if you can catch a U.S. Forest Service employee who’s not out conducting wildlife surveys, fighting forest fires, or doing maintenance. And if you have to wait for the station to open, there’s a mesmerizing hummingbird feeder and wildflower garden outside.

There are two primary ways to reach Kelly Creek, both scenic backroad drives and negotiable in ordinary vehicles under typical conditions: First, travelers can take Trout Creek Road (FR 250) out of Superior, Montana, conveniently located near I-90. The road twists relentlessly over the Bitterroot Divide, then descends into the inviting upper North Fork, before hitting the Kelly Creek junction. Stock up on gas and supplies before leaving Superior. For most anglers, Kelly Creek is a do-it-yourself expedition; come prepared with sufficient camping and hiking gear.

Or, approaching from the west, follow State Highway 11 north to the hamlet of Pierce, Idaho, and take twisting FR 250 to the North Fork. Then, proceed upstream to the Kelly Creek junction if you can resist fishing the inviting reaches along the way. FR 247 will get you to the North Fork, too, albeit much further downstream from Kelly. Consider bringing extra gas if you take this route unless you love hitchhiking. High-clearance, four-wheel-drive vehicles are useful for accessing remote portions of the upper watershed, but are not necessarily required to reach the Kelly Forks campground.

When navigating the Kelly Creek and North Fork backroads, consider Robert Frost’s famous poem, “The Road Not Taken”: “Two roads diverged in a wood, and I — / I took the one less traveled by, / And that has made all the difference.”

Jeff Erickson has logged thousands of road miles and 16 years as an environmental, land use, and outdoor recreation planner in Montana and Minnesota. In addition, his stories and photographs have been published in Montana Outdoors, Fly Fisherman, Fly Rod & Reel, and many other publications.

No Comments