21 Aug Dave Hodges: Sculpting Dreams into Reality

LATE JUNE BURNS HOT AND DRY at P Hanging Heart Ranch. Sun strikes the Yellowstone River on the southern border, flanked by cottonwoods, Russian olive trees and the fuchsia sprawl of wild roses, where a gravel road leads into Dave and Carmen Hodges’ ranch. With the Crazy Mountains as a backdrop, dust blooms in the distance, roiling behind a vintage tractor that bales stirrup-high grasses for wintering the Hodges’ longhorn cattle.

Dave Hodges is an artist, rancher and a working cattleman whose art reflects his daily connection to the land.

Once a competitive team roper, Dave bought his first longhorn bull to produce roping steers from their Hereford heifers. Now a 30-year member of the Texas Longhorn Breeders Association, he markets “steers with horns as large as 68 inches and handsome hides; maintenance-free cows that raise a good calf annually.”

He also extols longhorns in oil and in clay; Dave’s bronzes have received awards at Denver’s National Western Stock Show. His sculptures have been selected as Longhorn Association trophies and his life-sized monuments are installed in parks and university collections. Dave created his first bronze in 1982, Fancy Footwork, depicting a steer scratching his ear with a hind foot, a symbol of the real-life moments that he captures with a keen eye for ranch life.

“One of this [first] edition was purchased by President Reagan,” Carmen says of the sculpture that has long-since sold out. “It’s housed in the Ronald Reagan Library among his favorite things.”

In their own kitchen, Dave’s grandfather and his dog are pictured squatting on a Santa Fe street corner with two Native Americans. The 1900s photo is one of 500 Indian images that Erwin Ward gave his grandson from his years in New Mexico. Imprinted by his grandfather’s photographs, stories and a gift of two books of early C.M. Russell paintings, the Pennsylvania-born boy pioneered a new life out West. As an 11-year-old, Dave saved his money, surprising his parents with the arrival of his first 50 laying hens and then sold enough eggs to buy his first horse.

“We Hodges just never quit anything we start,” Dave confesses with a chuckle.

Disgruntled by the Abstract Expressionism taught at college, as a freshman he headed to horseshoeing school in New Mexico, and in 1972, Dave hired on as farrier at Montana’s Lion Head Ranch.

The ranch manager was acclaimed artist Jack Hines, and those years — talking art while shoeing horses, guiding trail rides, ranch and rodeo roping and packing in hunters — authenticate Dave’s artwork today.

Dave and Carmen share pioneer work ethics and family values that facilitated a union between art and cattle. Her grandparents homesteaded Boulder Valley, reportedly parenting the first white child on the then Crow Indian Reservation. Attending grades first though eighth in McLeod’s one-room schoolhouse, she, too, understood dreams wrangled from hard work.

The couple trapped furbearers and cleaned dudes’ rooms, earning ranch-related degrees, but in the early 1980s, if he could work off the tuition, Dave attended artist workshops hosted by Hines and his wife, renowned painter Jessica Zemsky.

Their classes attracted remarkable talent — Charles Fritz, Clyde Aspevig, Steve Aller, James Polson — passionate men with day jobs who painted until light’s last glimmer and bypassed night by talking of how and what to paint next. Their friendships have endured, and these men still people Dave’s ready stories about everything from bear hunting to plein air painting excursions.

“I learned a lot assisting guest sculptor Veryl Goodnight,” Dave recalls. And Robert Bateman explained why sculpting his wildlife subjects before painting keeps his work dimensional, honest: There’s no credible way to paint an animal on canvas without knowing its conformation from every angle. If an artist has difficulty balancing his armature, probably he’s rendering a posture his subject could never assume naturally. Dave took stock in the wisdom garnered from fellow artists.

In July 1986, the student became teacher when Jack Hines described “episodic” sculptures in Southwest Art. “Composing a sculpture so it captures the essence of a story brings together the best of design and of storytelling,” he wrote. He pictured Dave Hodges’ The Eye Of The Storm bronze of an impending horse-wreck to illustrate how sculpted narratives unfold — detailing why viewers fear for the rider; why surely profanity detailed the pack animals’ “family lineage and intelligence quotients.”

After years leasing land, the Hodges mortgaged their brand, using their cattle as collateral to buy their ranch, a “studio” where Dave has fed and bred, trained and packed, roped and stalked art subjects. Kinesthetic memories from rubbing down hundreds of horses have translated into equine bronzes with finely articulated musculature, landing his sculptures in American Academy of Equine Artists shows and the Kentucky Derby Museum at Churchill Downs. At the Montana Arts Council’s request, he created and presented Laura Bush with the state’s 2002 White House Christmas tree ornament.

Sculpting, Dave forms rubber molds off his clay models. Welding the foundry’s cast bronze, he does 90 percent of his own metal chasing. “Because painting a sculpture in full color can camouflage [both strengths and weaknesses] … I use traditional chemical patinas, allowing the sculpture to be fully exposed for what it is,” he explains.

Without color to help convey motion, Dave orchestrates movement “with light and shadow; positive and negative shapes.” His prelude is “thumbnail” clay sculptures; penciled design studies, choreographed by advice from the 1500s: “Benvenuto Cellini emphasized that ‘the art of sculpture has eight views, and they all must be equally good.’”

Revisiting Dave’s artwork in his May 1994 column, Hines heralded The Ridge Runners as moving statuary depicting “ … violent action, awesome in its speed and power.” Its seven running horses encapsulate firsthand experience of equine behavior and anatomy, interacting and reacting with one another in wild harmony, providing striking contrasts that make molded clay art.

Nowadays, Carmen runs Hodges Fine Art Gallery, located between Big Timber’s bank and bar on Main Street. “Where we head after work,” Dave quips, “depends on the kind of day she’s had!” Other Montana galleries that represent Hodge’s work are Tierney Fine Art in Bozeman and Missoula’s Schweyen/Gibson Gallery.

Embracing his role as a teacher, Dave’s creative process from armature to marketing is detailed in his own Book of Bronze. A good primer for spotting collectible sculptors, it’s also a great how-to manual for aspiring sculptors. He mirrors for student-sculptors what his dad, Steve modeled: how to question. He recommends ranching, where fashioning anything needed from moldering scraps is daily business.

Living fully informs Dave’s work, earning him accolades from fellow artists and ranchers. Studying his cast bronzes and painted subjects, his audience may hear birdsong, brace against ice-blended winds or inhale sage-scented air. “If my art is good,” Dave concludes, “it tells my story also.”

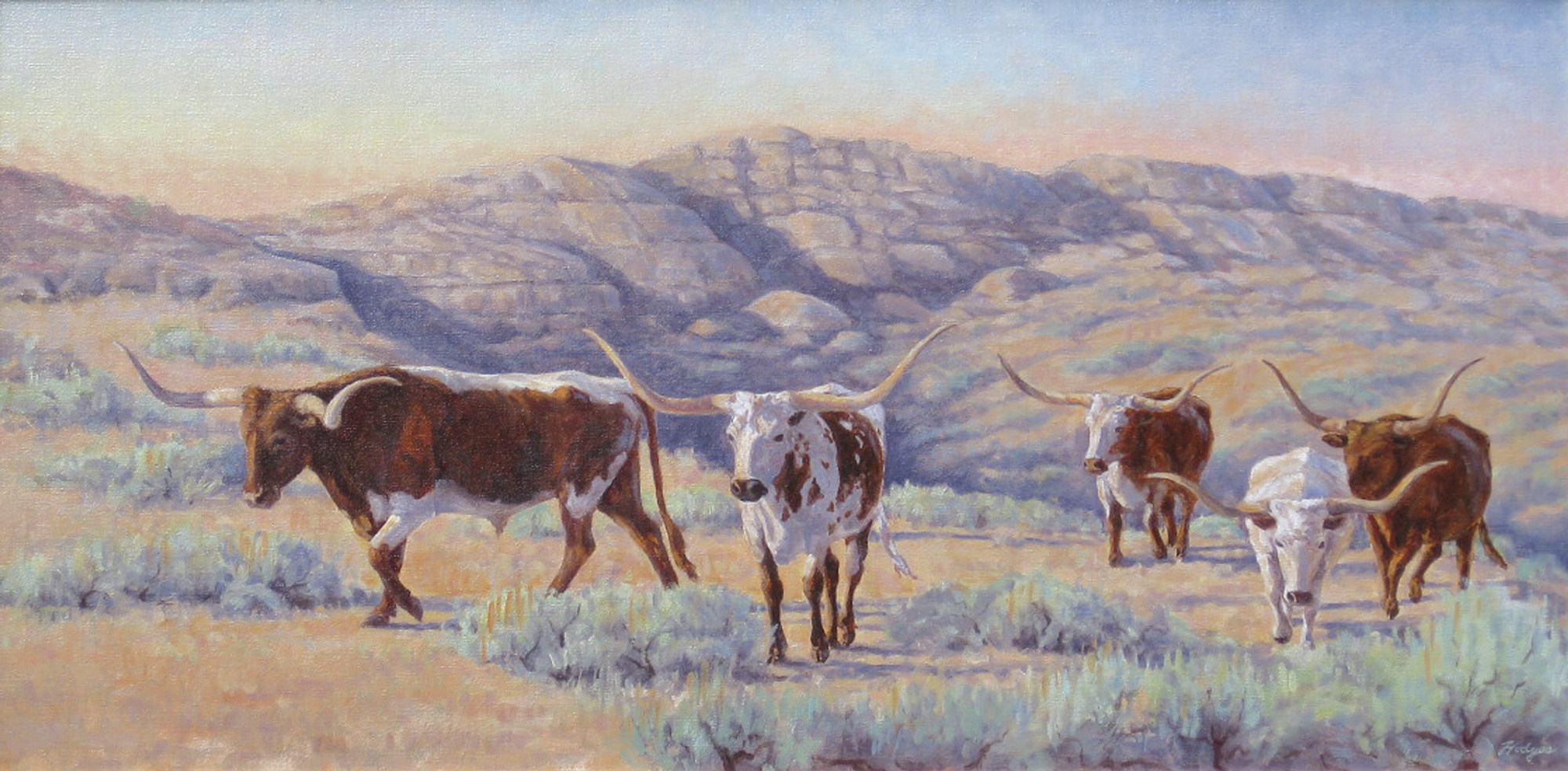

- “Early Morning Move” | Oil on Linen | 30″ x 15″

- Carmen and Dave in the backyard of their Big Timber ranch on the eve of their 32nd wedding anniversary.

- “Down Hill From Here” | 2009 | Bronze |Limited Edition of 15 | 27″ x 21″

- “Trail Blazer” | 2009 | Bronze | 30″ x 21″

- The unveiling of a sculpture of internationally renowned opera singer Marilyn Horne at the Blaisdell Arts and Cultural Center in Bradford, PA. On stage are Marilyn Horne, Dave Hodges and University President Livingston Alexander.

No Comments