10 Feb Images of the West: Cutthroat Goals

One warm summer day in 2002, a young boy in the Jewel Basin felt the end of his fishing rod bend violently. A large fish was on the end of his line, far out in the lake, 4 pounds and 22 inches-worth. It had the weight of history to it. Five years earlier, as a tiny westslope cutthroat juvenile, it had been dumped into the remote four-acre lake by helicopter along with thousands of other fingerlings. They grew and thrived. Such successful efforts are worth noting as Montana strives to restore cutthroat to their former place and prominence; it’s only fitting, of course, since they are our official state fish.

When the Corps of Discovery penetrated the Missouri River to the Great Falls in 1805, Silas Goodrich, the crew’s best fisherman, landed the first cutthroat seen by white men and thus began the Montana tradition of reeling sport trout out of our waters. Captain Lewis endowed it with the scientific name, Salmo Clarkii, in honor of his fellow captain William Clark. Up until Goodrich reached Montana waters, he had been catching endless numbers of catfish on the lower Missouri; his fellow crewmembers likely welcomed the change in diet. Goodrich could have hardly known it, but generations of anglers would follow his lead.

Today, however, cutthroat are a species in trouble, making active fisheries reintroduction of cutts a management cornerstone of the state Fish, Wildlife and Park’s (FWP) goals.

How did this happen? Native populations like westslope cutthroat were displaced when sportsmen stocked Montana rivers with what seemed like more desirable sport fish, including rainbow trout and eastern brookies. Trouble was, the new guys swarmed the original populations. Reversing the process has been complicated and sometimes controversial.

For nearly 100 years, vigorous efforts have been underway across Montana to restore habitat and reintroduce cutthroat to streams and rivers known to have harbored these trout historically. Part of that effort revolves around planting young trout into old habitat.

Fish planting is decades old. As early as the 1920s, sportsmen’s organizations pressured government officials to enhance fishing opportunities in order to attract tourists to Montana. The fish hatchery concept arose out of this effort in the 1930s, and featured the rearing of young sport trout to be shipped to far off lakes and streams. Classic examples include the Creston and Big Arm fish hatcheries in northwest Montana. The Creston Hatchery had the specific goal of raising young rainbow trout to transplant into backcountry lakes in Glacier National Park.

Fish rearing was one thing, but placement of those fish was another. By then, the fishery dynamics had been upset, requiring whole new management plans to rebalance populations back to their original dimensions. This involved poisoning selected lakes that were colonized by introduced species, then reintroducing native populations to the purified waters, such as those in the Jewel Basin and elsewhere in western Montana. With time and considerable effort, we’re improving the science of balancing biodiversity.

As late as 1968, Glacier Park officials were still engaged in planting cutthroat into some of the larger lakes (Bowman and Kintla), hoping to repopulate whole drainages with natives. Then, as if on cue, this brought about another problem. Many of the park’s lakes contained holdout populations of Dolly Varden (bull trout) that are highly predacious. So most of the fingerling cutthroat that were emptied out of trucks into Bowman and Kintla lakes became easy prey for the bull trout. It was like feeding time at the zoo.

In his 1977 testimony before the Montana legislature to advocate for designating the cutthroat as our official state fish, the chief of the state’s fisheries division wrote: “Probably more than any species, the cutthroat trout symbolizes the quality we are striving for … in Montana. Just as this fish requires a quality habitat if he is to survive, Montanans as a people are striving for a quality of life already lost in many parts of this nation.” After due debate, the cutthroat won out over the paddlefish, the Dolly Varden and the Arctic grayling.

Land a 9-inch cutt now and you should have the realization that it probably took about a decade to build that fish. And then cheerfully put him back so he can have another few years. The fact is, cutthroat are de riguer on the Flathead River system and other watersheds in western Montana, their populations managed assiduously by FWP. Tourists from all over America arrive in Montana hoping to catch this ancient fish and hold it in their hands. The quintessential question from many visitors is, “Where can I catch some natives?” So the quest for sport — and history, is on.

Think of it this way: If you are anywhere east of the Continental Divide in Montana and reach down and scoop up a handful of dirt, you’re holding a piece of history, a chunk of the Louisiana Purchase, if you will. You can thank Thomas Jefferson for that. Similarly, the next time you pull a cutthroat trout from your landing net, handle with care and reverence. It’s a piece of history also. And think of Silas Goodrich, Montana’s first modern angler.

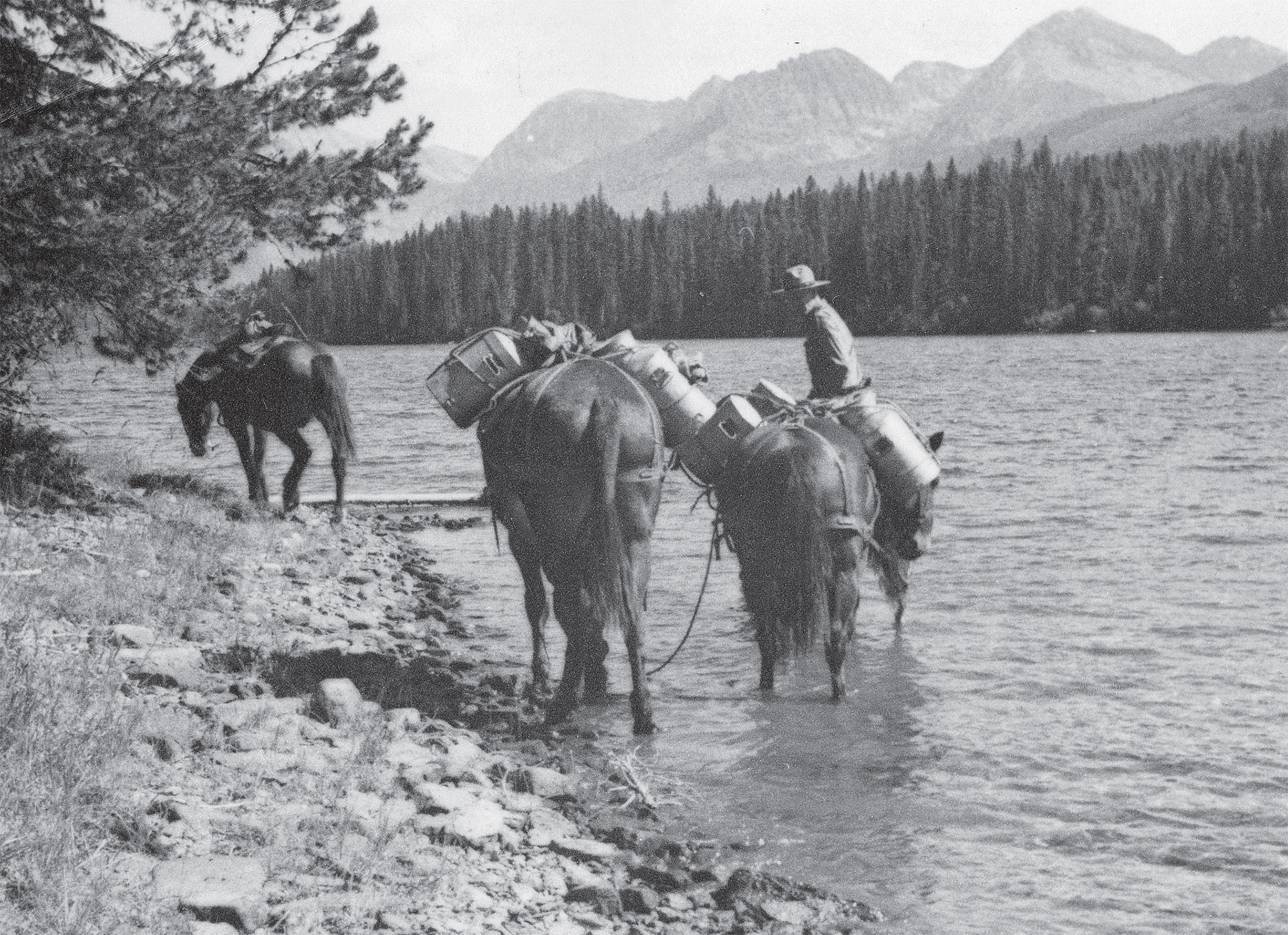

- Ranger and mules, loaded with fish cans, at the foot of Logging Lake, (September 1943). | Photo Courtesy of Glacier National Park archives

- A closer look at the fish bags rangers used to transport trout.

- Weighing fish to transfer from truck to pack in July 1941. Taken at Many Glacier horse corral — fish heading to Cracker Lake. | Photo Courtesy of Glacier National Park archives

- Weighing fish to transport to Glacier National Park from ponds at Creston Fish Hatchery, (August 1941). | Photo Courtesy of Glacier National Park Archives

- An unidentified ranger emptying cans of fish at the foot of Lake McDonald, (September 1943). | Photo Courtesy of Glacier National Park archives

No Comments