04 Feb Conflict on Idaho’s Rapid River

In the world of American freshwater angling, the Nez Perce tribe occupies a special place. Take, for example, the case of Rapid River, a relatively obscure stream approximately 150 miles north of Boise, Idaho. The trout-filled, remote, and rugged upper 27-mile section, accessible only by trail, earned protection with a Wild and Scenic River designation in 1975. But it’s the relatively tame lower 4 miles of the river that unite the best Nez Perce salmon fishers every spring during Chinook season. This lower section supplies the water for a salmon hatchery before meandering through a series of pastures and two housing subdivisions. It then crosses Highway 95 and merges with the Little Salmon River, which enters the Main Salmon River 6 miles downstream in Riggins, Idaho.

A Nez Perce woman wields a 16-foot long dipnet used to sweep a pool for Chinook salmon.

The Nez Perce call Rapid River Yáwwinma, meaning something close to “Coldwater River.” The water’s cool year-round temperatures make it ideal for raising salmonids. And although they fish many other rivers, the majority of Nez Perce families in the area can quickly and easily access Rapid River during spring Chinook season. They’ve been fishing here for thousands of years using the same methods and techniques: gaffing, dip netting, spearing, and snagging. Like other Western tribes, the Nez Perce believe they have inhabited their homelands since “time immemorial,” a phrase that denotes a point far beyond human recollection and recorded history.

Unlike most other tribes, though, the Nez Perce have no migration story in their oral histories, no recounting of an exodus or an emigration. What’s more, there is simply no archaeological or linguistic evidence to support the idea that the Nez Perce people have ever resided anywhere outside the Columbia Basin, a point they’ve been making at least since Lewis and Clark first encountered them on Weippe Prairie in 1805.

The gaff hooks used vary dramatically in size.

Indeed, the site of the oldest human habitation in North America is now an ancient Nez Perce village. Called Nipéhe by the Nez Perce and referred to as Cooper’s Ferry by archaeologists, the site is 74 miles by car from the mouth of Rapid River. Indeed, the seasonal Nez Perce “tent cities” that suddenly materialize each spring during Chinook season beside Highway 95 may be nothing more than a continuation of that prehistoric seasonal village.

Regardless, news confirming that the village of Nipéhe has been around for more than 16,000 years broke last September. It crushed the idea that the first human migrations into North America came via an ice-free corridor in central Canada. Sixteen thousand years ago, with the Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets still in place, the Canadian interior would have been absolutely inaccessible to human migration. Instead, says Oregon State University archaeologist Loren Davis, “Early peoples moving south along the Pacific Coast would have encountered the Columbia River as the first place below the glaciers where they could easily walk and paddle in to North America. Essentially, the Columbia River corridor was the first off-ramp of a Pacific Coast migration route.”

Davis first discovered the Nipéhe site as a graduate student. In 2009, he returned to the site as a professor and established it as a field camp for his students. He soon involved the tribe and other colleagues who helped him work the site for a decade. This year, they publicly revealed some of their findings, which included animal bones and charcoal conclusively dating to 16,560 years ago.

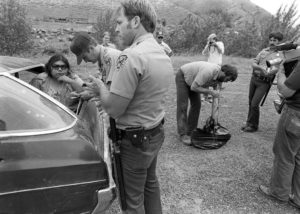

Idaho Fish and Game officers write tickets and confiscate salmon at Rapid River in 1980.

That date implies that people were around to witness the prehistoric floods of biblical proportions in the Northwest that apparently wiped out all traces of other such ancient villages in the region. The cataclysmic Missoula floods, for instance, periodically swept down the Clark Fork and Columbia rivers whenever the ice dam on glacial Lake Missoula burst. Those floods left behind, among other geological features, the enormous “dry falls” and channeled scablands of Eastern Washington, much as the Bonneville Flood eventually left behind the Great Salt Lake. Nipéhe just happened to sit high enough in elevation to avoid destruction.

Sixteen thousand years ago, both frustrated and abetted by climate change, Pacific trout and salmon species were still expanding their ranges. Given Rapid River’s immediate proximity to the Main Salmon River, we can guess that all six of Rapid River’s indigenous food species — bull trout, cutthroat, rainbow, whitefish, steelhead, and Chinook — had probably already colonized Rapid River, whether or not ancestors of the Nez Perce had or had not begun fishing for them. Regardless, Idaho’s Salmon River has historically been the most productive tributary for salmon and steelhead in the Columbia Basin. And it still is.

Nez Perce men pose for the press during the conflict at Rapid River in 1980.

Tragically, however, its Chinook run, once estimated at 3.25 million, has shriveled to less than 10 percent of that historic abundance, and the wild fish populations continue to crash. Hatchery fish now constitute at least 75 percent of the Chinook returning to the Snake River. At Rapid River, it’s closer to 100 percent.

Built in 1964 by Idaho Power to mitigate the complete extinction of the runs above their Hells Canyon dams, the Rapid River Hatchery annually releases about 3 million spring Chinook smolts directly into the river. Less than 1 percent of them return as adults. Ocean conditions, predators (especially humans), and eight high dams on the Columbia prove too much for the overwhelming majority.

One year in the 1960s, as few as 200 adult Chinook returned to Rapid River. Then, with salmon runs still setting record lows throughout the Northwest, the State of Idaho attempted to enforce conservation closures to salmon fishing on Rapid River. For two seasons (1979 and 1980), the Nez Perce salmon fishers defied armed aggression and risked their lives to preserve their federally recognized treaty rights to fish in all of their “usual and accustomed places.”

Even when SWAT team snipers were poised on ridgetops, the Nez Perce miraculously averted bloodshed through peaceful civil disobedience. In excessive shows of force, state troopers armed with shotguns and batons, and Idaho Fish and Game officers carrying sidearms, regularly invaded Nez Perce camps on the river and searched their vehicles. State agents issued scores of citations, made copious group arrests, and jailed numerous Nez Perce salmon fishers. In one case, a judge set bail at $75,000 and held the defendant for 186 days. In general, the Nez Perce met the State of Idaho’s aggressive and heavily armed police actions with patience and persistence, but also with humor and angry ridicule that sometimes ended in physical altercations. Each year, they attempted to appease the state by agreeing to self-regulate their fishing (as they have always done) and limit their catch by fishing exclusively on weekends.

James Blackeagle prepares to put three of his recently caught chinook on ice.

In 1981, the conflict ended up in court where Idaho District Judge George Reinhardt threw out all the charges against the tribe and the men, women, and children who had been cited and/or arrested. The judge had ample grounds to dismiss the case, including treaty rights, sovereignty, and religious freedom. Instead, he chose to dismiss it on the basis of the state’s refusal to allow the Nez Perce “an opportunity to participate” in a “meaningful way with the state relative to developing regulations” that “are clearly necessary if the spring Chinook salmon is to survive.”

Acknowledging the state’s responsibility to share the power to regulate the salmon fishery with the tribe eventually produced numerous benefits for all. Tensions between the state and the tribe continued in the short term, of course, but they have never again become militant. Today, failing to consult with the tribe on any number of conservation matters, let alone the closure of a salmon fishery, would be unthinkable. What’s more, the Nez Perce have often succeeded where the state has failed.

For example, the state’s attempts to restore Snake River coho salmon collapsed completely in the 1960s, resulting in the species extinction in Idaho in 1988. To bring any species back from extinction is an extraordinary achievement, a rare accomplishment anywhere in the world. But in the case of the Snake River coho, the Nez Perce achieved it using eggs from lower Columbia stocks.

With the tribe’s blessing, Idaho opened its first coho season to non- Native Americans five years ago. On October 21, 2015, the National Congress of American Indians recognized the Nez Perce tribe’s Fisheries Department with “High Honors,” and they were given the prestigious Honoring Nations Award from the Harvard Kennedy School of Government’s Project on American Indian Economic Development.

If freshwater angling — whether fly fishing, lure fishing, bait fishing, or gaffing for salmon — is to have a future, we need to put aside our sectarian beliefs and differences and work together. The past is the only direction we can learn from, and in the case of the Nez Perce, theirs offers us more than hope. It’s exemplary.

No Comments