12 Dec CHASING 40

Is the next state-record northern pike swimming in Fort Peck Reservoir? A hardy crew of ice anglers is betting their spears on it

Joe Horn briefly disappears in a cloud of blue smoke. His airboat has just fired to life, and after a sputter and a chug, the engine roars in the thin air of a frigid February morning, turning on a giant fan inside a metal cage at the stern of the boat. This style of boat — flat-bottomed and broad-beamed, with a push fan providing tooth-rattling propulsion — evolved in the ‘gator swamps of Louisiana and Florida. It seems out of place on the barren shoreline of frozen Fort Peck Reservoir, but then so does Horn. If Neptune had a dirty uncle, he might resemble Horn, whose stringy goatee and pug nose make him look like a member of a motorcycle gang or a bayou rat, with a boat to match.

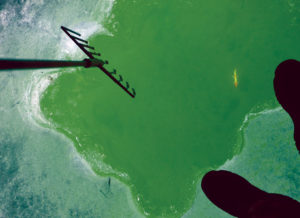

Joe Horn clears overnight ice out of a spearing hole in a frozen bay of Fort Peck Reservoir. opposite: A pikespearing camp on frozen Fort Peck.

But Horn, a retired Glasgow city cop, isn’t chasing swamp critters on frozen Fort Peck — he’s hunting ‘gators of a different kind: big, slab-sided northern pike. He uses the airboat to access the remote bays of the sprawling prairie reservoir, where he’ll erect a vinyl tent over a grave-sized hole cut in the 3-foot-thick ice, unfold a lawn chair, and spend hours gazing into the greenish water, a 7-foot spear in his gloved hand.

The airboat is the safest way to cross the ice, which can become rotten around shallow points, and which, out on the main lake, breaks and cleaves in dangerous pressure heaves that are often obscured by snow. Those fault lines — or rather the thin ice between the moving plates — sink a couple of four wheelers and pickups every winter on the reservoir. It’s one reason most Fort Peck anglers fish in pairs and groups; the lake is a dangerous place for a solitary angler.

But the danger doesn’t deter Horn, nor a legion of ice spearers, hardy hunters who spend days and weeks on frozen, desolate, wind-pounded Fort Peck, waiting for the biggest fish in Eastern Montana to swim under their holes. “Watching Norwegian television. That’s what some people call what we do,” says Horn, who wears noise-blocking earmuffs as he steers his boat across the ice. “You sit all day just looking into a hole in the ice. Hours of boredom interrupted by seconds of excitement.”

Joe Horn shows his hand-carved pike decoy.

These spear fishers are mainly hunting big northern pike, though they also take walleye and lake trout. All three species are apex predators, themselves hunting under the ice. The spearers lure their prey by dangling a decoy — usually a brightly painted imitation of a sucker or a perch — in their hole. When the predator comes to ambush the decoy, they thrust their long, sharp spears into the water, hoping to impale the fish or at least stab deeply enough into its back so that, in its twisting and writhing, the fish doesn’t shake loose.

The spears, which are attached to rope, are then retrieved, the fish removed, admired — sometimes measured — and laid out on the ice. There is no catch-and-release when it comes to spear fishing. Then the process repeats. On their best days, Fort Peck’s spear fishermen encounter dozens of fish, and might spear a 10-fish limit of big pike.

But they’re really holding out for a single specimen, a pike so big that it will break the current Montana state record, which is a 37.5-pounder caught nearly 50 years ago in the Tongue River Reservoir near the Wyoming border. “She’s out there,” Horn says with assurance. “There’s a 40-pounder out there.”

Horn says members of the spearing fraternity — nearly all men — swap stories of outsized pike that have darted through spearing holes too quickly for them to throw a spear. They talk of pike with heads the size of Chesapeake Bay retrievers that nosed to the edge of the hole to inspect their decoys but didn’t come close enough for a shot.

“Clay Kittleson [a local spearer] swears he had a 40-pounder swim into his hole off Shafthouse Point,” says Horn, describing a location just off the face of the dam. “He was jawing with his buddy, and they both looked down and saw it, and he says it was longer than his hole, which is 4 feet or better. They both threw but missed.”

The trophy-pike hunters say that Fort Peck has all the ingredients required to produce giant northerns, including abundant forage, good spawning and rearing habitat, and relatively little fishing pressure.

But Heath Headley, the Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks fisheries biologist who oversees Fort Peck’s management, isn’t so sure. “Is Fort Peck capable of achieving a 40-pounder? I’d like to think so,” says Headley, “but biologically and habitat-wise, I don’t think it’s feasible.”

Decoys are suspended in holes and gently jigged while a spearer waits for a pike to inspect the bait.

Headley says that the reservoir might have many of the ingredients required to produce outsized pike, but he thinks the boom-and-bust water management of the lake limits the growth potential of northerns, which require flooded shoreline vegetation to spawn and then the right set of habitat combinations as they mature. “A 40-pound fish isn’t quite a unicorn, but it’s close,” says Headley. “Even in Northern Canada, they’re not seeing 40-pound pike. They’re definitely seeing 30-pounders, but even those are rare. And that’s classic, near-perfect pike habitat with relatively little fishing pressure.”

As a reservoir designed for, among other things, storage to supply the Missouri River Basin with irrigation, and municipal and barge-floating water as far downstream as St. Louis, Fort Peck’s level fluctuates seasonally as it’s drawn to supply downstream demand. In years with low mountain snowpack and little prairie rainfall, the reservoir’s level drops even farther. At full pool, Fort Peck’s elevation is 2,250 feet above sea level. But in 2007, the lake dropped to its lowest level on record, to 2,196 feet above sea level. That’s a 54-foot differential, and on Fort Peck, 54 feet means hundreds of miles of exposed shale points and gumbo shorelines. Those are the worst of times for fish like pike, which require submerged shoreline vegetation. It’s in years when the water comes up, covering a few more inches of willows, thistle, and the noxious weed tamarisk, that pike thrive.

Fort Peck’s historic drawdown in 2007 was short-lived. Heavy runoff from record snowfall in 2011 pushed the lake to its record high, and produced millions of pike in the inundated vegetation. “The bigger fish that people are catching now are probably the result of those good water years,” says Headley. “But we don’t string enough good water years together to grow pike consistently, and I think that’s the limiting factor.”

Brett Johnson, a fisheries professor at Colorado State University and a national expert in the bioenergetics of fish, says big pike need time and the right forage to reach trophy dimensions. Worldwide, he says, a 10-year-old pike is about 30 inches long and weighs 7 pounds, and some highly productive reservoirs can produce larger pike more quickly. On Rifle Gap Reservoir in Colorado, where he’s researched the growth rates of northerns, a 10-year-old pike grew to 32 pounds. “I’d guess Fort Peck is not as productive as that,” says Johnson. “But I can say that a 40-pound pike would be quite a bit older than 10.”

In other words, probably older than the age-class of Fort Peck’s pike that were produced by the high-water years starting in 2011.

The Food Factor

On most prairie reservoirs and lakes, pike prey on perch, suckers, and even carp. All those forage species are available in Fort Peck, as well as smaller morsels, such as spottail shiners, immature crappie, and even little pike. But years ago, fisheries managers introduced an oil-rich member of the herring family to the lake. Called cisco, the forage fish grow to about a foot long and offer high-fat vittles for the predators big enough to eat them, and also for those big enough to get out in the deeper, cooler water where schools of these fish prefer to live.

The author hoists an eating-sized pike that he speared on Fort Peck Reservoir.

Horn and other pike spearers think the cisco are Fort Peck’s trump card in the record-fish game. “Cisco are a big bait, and they grow big predators,” says Horn. “I think the reason most open-water fishermen don’t see huge pike on Fort Peck is because they’re out in open water, feeding on cisco. But in the wintertime, those cisco come shallow — it’s nothing to see a few schools of them a day through the ice — and we see both lake trout and pike right along with them.”

Johnson agrees that the path to a state-record pike is through cisco, but he says it takes a prodigious amount of groceries to put on the pounds. “Pike at Rifle Gap Reservoir needed to eat about 375 catchable, 10-inch rainbows to get to age 10 and 32 pounds,” he says. “In Fort Peck, to get that last 8 pounds of growth — to reach 40 pounds — it’s probably going to take something like 750 ciscos total. It all depends on how fast they are growing later in life; I’d bet it could be much more than 750 to get a pike to 40 pounds.”

Headley says that his fisheries crew has been sampling predator species in the deeper depths of Fort Peck, and while they’ve turned up a few big pike, they haven’t seen one much over 20 pounds. But he does acknowledge that Fort Peck’s immense size and relative desolation are factors that help it produce outsized fish. “In terms of angling pressure per square mile, Fort Peck has much less pressure than other pike fisheries,” says Headley. “Add to that, that most Fort Peck anglers — something like 80 percent of open-water fishermen, based on years of creel surveys — are coming to target walleye. And surprisingly, the next most popular species on Fort Peck is Chinook salmon. Pike are next in popularity, but it’s a relatively low number that are fishing specifically for them. For most anglers, pike are an opportunistic catch.”

Fellowship of the spear

That’s not the case with the winter spearing crew; they’re almost single-mindedly focused on big pike.

“I’ve speared nine pike over 20 pounds,” says one Glasgow spearer, who gushed about Fort Peck’s winter fishery and its trophy potential, then asked that his name not be used in this story. That’s how secretive many of this fraternity are about their quest for state record. “The biggest I’ve speared is 27 pounds. I’ve heard of 30-pounders being caught, but they were never actually weighed.”

In order for pike to grow to record-class size, they need forage, space, and shal- low-water habitat.

The consensus of spearers is that the biggest fish of the season are generally encountered just as the ice starts to leave the lake. That’s one reason Horn invested in his airboat; it allows him to access the ice even after the shoreline starts to melt. “Spearing is best later on the ice. It’s when the guys who are really serious about big fish start to go out,” says the angler who asked not to be identified. “But safety becomes an issue. Then again, safety is always an issue on Fort Peck because of how big a body of water it is, and because the ice conditions can change so quickly.”

Asked to pick the best week of the winter to spear target pike, Headley says it extends into early March. “I think once that shoreline ice starts to go, those big female northerns — full of eggs — start moving into the shallow water. They can sense that little spike in water temperature and are staging before the spawn. But it’s also just about the worst time to be out on that ice.”

Horn says the risk is worth it. “I want to be out there when the ice is starting to turn milky and honeycombing,” he says. “You have to pick your places and your spots — and that airboat can help cover open water to get to the good ice — but you can have days when you’re passing 20-pound and bigger pike, because you know that there are bigger ones out there.”

No Comments