30 May Cataloging the Untrammeled

I hike in the dust of Morley, my one-eyed mule guide, with each step taking me deeper into the wilderness. He saunters up the trail, slightly swaying under the weight of my food. His deliberate and practical rhythm slows my anxiousness and excitement into contented observation and awareness. These are new woods to me, thick with old larch that survived the last burn 100 years ago, standing tall above brushy huckleberries. The larches still hold those scorched scars, resilient reminders of survival. Purple clematis gathers around their bases.

I fall into Morley’s rhythm, watching him gracefully trample along the trail. As dirt settles on my face, I ask him to show me how to hike this trail, how to be in and of this place. He does so in his slow commitment to every step and deliberate pauses to bite the fiery heads off clusters of Indian paintbrush.

Morley stands ready to be unloaded. The Bob Marshall Wilderness Foundation uses experienced packers and teams of mules and horses to help with trail work and volunteer trips into the backcountry. | Photo by Michael Garrigan

Morley is the last of the mules, guided along by the lead rope hanging from his jaw, but it’s tied with a loose knot, and he easily breaks away from the pack. He doesn’t do this to annoy the rest of them or as an affront to their unity; he does this because he smells something interesting, because he is hungry, because he wants to. He never runs away into the woods — he just goes at his own pace while he is free. Every so often, Frank gets off his mule, walks back to Morley, and reties him to the pack string. Morley nods and stays tied until he decides not to be.

Morley knows where he’s going; I do not. He’s been down this trail before; I have not. He poops on the trail; I do not. He isn’t afraid of grizzlies; I am. His four legs quicken his pace; my two legs strain to keep up. He eats whatever plants grow along the trail; I search only for huckleberries. He does not get to choose who he is tied to; I do. He cannot tie himself back to the pack string; I can. When he breaks free, he is truly free, unencumbered; when I break free, I have to work to stay unbound, to not tie myself back to the narrative string I was just part of.

I’ve driven over 3,000 miles across eight states to get here, living out of my truck and sleeping wherever I end up after long days of driving. I’ve broken the string holding me to the rest of my life, and no one is here to retie me. Untethered, I’m hiking along the Big River Trail deep into the Great Bear Wilderness as part of an artist residency with the Bob Marshall Wilderness Foundation and Flathead National Forest. My only goal is to gather whatever I can and write some poems, catch a few westslope cutthroat trout, hike up some mountains, and not succumb to loneliness or go completely feral.

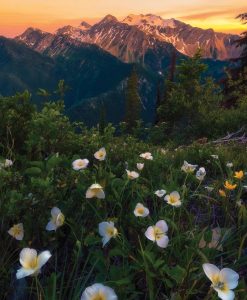

The mountainous Flathead National Forest is full of wildflowers during the summer months. Spruce Peak, Vinegar Mountain, and Mount Baptiste mark the high points of the Great Bear Wilderness. | Photo by Zack Clothier

Spruce Park

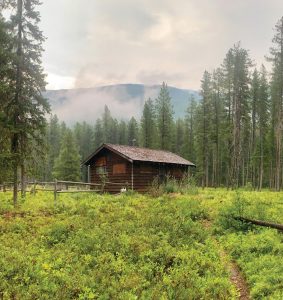

Situated a few hundred feet from a steep ledge slowly crumbling into the river, Spruce Park is a utilitarian-style cabin built with dimensional lumber — no old-school notches, no logs. It’s eyed with clunky shutters on each wall, and a wrought-iron door does little to keep out horseflies. There is no doorknob, just a string tied to a metal rod that, when pulled down, lifts the inside latch out of a makeshift grooved coupling. The cabin was built to be used only for a few years before a proposed dam would have drowned the valley and shot the river under the mountains into the Hungry Horse Reservoir, but, thanks to the Wilderness Act, the dam was never constructed. Spruce Park is a totem of the legacy of conservation that has shaped this 1,500-square-mile wilderness complex.

The meager structure holds a wood stove, a table by the window, one mouse-proof aluminum cupboard, drawers filled with duct tape and dead batteries, a sink with no running water, a gas stove that you should never bake in unless you want the cabin to smell like burning rodents, and a couple of beds and bunks.

Spruce Park is enclosed by a lumbering lodgepole pine fence opening to a ledge overlooking the Middle Fork of the Flathead River. There’s an old corral and a tool shed with one large pack rat living in it. White tufts of pearly everlasting grow throughout the meadow along trails that mules and people have made. When I lie down in bed I look out a torn screen into the night sky and watch constellations I never see back home. I fall asleep to skittering mice and wake to the occasional snap of their necks in the traps. I feel bad, knowing that this is more their home than it’ll ever be mine, but they don’t seem to know how to keep the peace.

The Great Bear Wilderness has one of the highest densities of grizzly bears in the lower 48 states. | Photo by Don Jones

I hike the Big River Trail and climb mountains and wade in the river, but I never leave this ravine of billion-year-old belt rock, trying to notice everything I can and learn all the names of the wildflowers, hoping to eventually become something more than just a traveler passing through. When we become of a place, the gap between visitor and local is closed through an awareness of all the interconnections that exist without us, thrive without us, live without us. Every day, I try to sink a little deeper into this ancient sea, to get tangled in the web of connections that my own solitude enables me to explore, to drown in the wildness of this place.

Trout, Mountain Whitefish, and Bears

I cast a caddis, trying to land my first westslope cutthroat trout, but instead a mountain whitefish grabs it and darts downstream, jumping a few times before diving. I’m in my sandals, water up to my knees, the sun slowly setting, with the river brushing whitefish scales off my hands as I release the fish into the current. They are feisty, and I fall in love with their monochromatic shades of white and gray, a palette cleanser to all the brightness I am surrounded by. I start catching cutthroats when I move into faster water. They are just as feisty, but instead of diving down into the pool, they shoot across the water, away in all directions. They jump, they turn, they refuse to stay still. They are streaks of light cascading and slicing; they are fierce in their love for anything floating on the surface that might be food.

I wouldn’t be able to be here alone for two weeks without these fish. They are constant companions. I talk to them while I sit on the rocks and watch the water, skipping stones over their heads, trying to teach them a code of patterns, a Morse code, a language for us to speak. They only respond when I throw something light that floats. I accept this and speak their language as well as I can. Each day, I learn a few more phrases — at the head of riffles, skitter caddis in sunrise, purple foam in wildfire haze, slow down, dip hat in water to cool down, cow parsnip in the peripheral, deadwood scripture, rock liturgy, river theology. With each phrase, I feel closer to them, closer to being accepted by them, closer to the woods that shade them, closer to the water that feeds them.

I’m in the middle of a cast when I see a puff of dust on the scree slope 50 yards upstream of me. I stop and watch a grizzly clamber down the loose escarpment, boulders and stones rolling from its lumbering, until it reaches a little copse of pine that has somehow taken hold. It doesn’t notice me as it digs around the roots.

Spruce Park Cabin, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, is a rustic cabin that is now used by backcountry rangers and artists in residence. | Photo by Michael Garrigan

I stand and stare at the bear even though I should be walking back to my pack to put my hiking boots on and be near my U.S. Forest Service radio and hiking poles. I should be hiking downstream before it notices me, but instead, I just watch, and when the wind shifts at my back, immediately the grizzly pokes its head out from behind one of the pines. It sniffs and stares at me standing in the water in my sandals, fly rod in hand, fly line pulling downstream, and I think I finally understand what Buddhists mean when they say that awareness is the ultimate existence, that, when your ego dies, you do not lose yourself, you just become the world around you, you connect to the quotidian sacredness. There’s freedom in the presence of something that could easily kill you. There’s freedom in knowing that you wouldn’t be found for days, that your life would linger until your death is acknowledged. A bardo of the in-between. Our awareness is like the water to these mountains. Without water, these mountains would not exist. They would not be. Without awareness, our world does not exist, our life does not linger, and our death does not approach — we are merely functioning.

The grizzly and I stare at each other, neither of us moving. I don’t know what to do, so I ask the bear what its favorite Tom Petty song is. It says “Even the Losers,” and I say “Walls,” and we both agree that Echo is an incredibly underrated album. I start singing “You Don’t Know How It Feels,” and just as I start the “let’s roll another joint” line, the bear grunts, turns, and lopes upstream, slowly making its way back up the scree slope and into the thick grove of aspen, into the old burn.

A Ledge and a River

Each morning, I take my coffee and sit on the ledge as first light touches Red Sky Mountain and slowly makes its way down to the river until the sun is high enough to cast fortress-dark tree shadows across everything. I watch the bald ridge, looking for any signs of movement, waiting for words to come.

Each evening, I take my drink and sit on the ledge as last light fades behind Red Sky Mountain. The shadows reach up instead of down, the whole valley lifting out of itself for a few liminal moments until it’s too dark for me to write, and bats start swooping across the ravine.

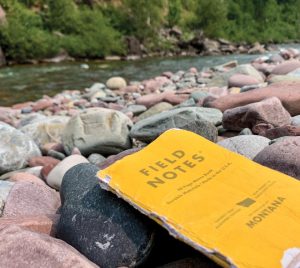

This well-worn book belonging to the author is, indeed, full of notes from the field: meanderings, sketches, parts of poems, and the beginning of this essay. | Photo by Michael Garrigan

It seems that gods appear on the edges and ledges of this world, and for me to reach the sacred, I need to find the everyday ecotones — where water meets bank, where hand touches huckleberry, where light touches ridge, where paw meets mud, where pen meets paper, where mouse meets trap.

Each afternoon, in the heat, when time stretches and loneliness lays across everything like wildfire haze, dimming all the colors, I go to the river, strip to my boxers, and slowly, methodically walk into the deep pool behind the cabin. I step until my waist is wet and splash glacial water onto my chest and head, acclimating to it. I do this for 15 or 20 minutes, staring into the river, sometimes closing my eyes and letting the everythingness become a nothingness that unravels itself into

an awareness.

I swim across the river and sit on a long ledge of rock. Before swimming back to shore, I pick up rocks rounded smooth by thousands of years of water — a slower form of becoming — and think that perhaps this is the transubstantiation I believe in, a slow shaping of ourselves by this world until we are smooth enough to glide across the skin of the river to the far bank, where we rest and gather and become, together.

What’s Left Behind

Something is left behind on every journey, and in that space, something is created. Trout, when they break the surface, leave the security of their river home and return as another fish, their pursuit for what is above shifting them into another life that knows wildfire smoke and dry light. Elk walk until they can’t, and they fall and wait for the river to take them, leaving behind antlers that gather stone and tufts of hair that eagles use to soften their nests. Huckleberries are plucked, and in that space, another leaf grows.

On day 15, Morley returns, all my gear is packed onto the mules’ backs, and Frank leads us to the trailhead. I pick wildflowers on my way out as I fall into Morley’s rhythm, and when I get back to my truck, I’ll tuck them into a collection of Thomas Merton essays, hoping that when I find them years later, I’ll catch a faint scent of this valley and somehow return to it.

The Middle Fork of the Flathead River is part of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers system and traverses through the Great Bear Wilderness, where it is home to native westslope cutthroat trout, bull trout, and mountain whitefish. | Photo by Pete Strazdas

I can’t help but wonder what part of me was left behind, sitting on the ledge watching the river, wandering further into those stands of pine and tamarack and deep pools of emerald water following Morley’s steady one-eyed gaze into the dusty last light. I pray the marks of that separation grow with me like the larch holding those burn scars, becoming another graft of skin across my chest I can feel with each breath.

Michael Garrigan writes and teaches along the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania. He is the author of the poetry collections River, Amen, and Robbing the Pillars and was an artist in residence for the Bob Marshall Wilderness Foundation; mgarrigan.com.

No Comments