05 Oct Books: Reading the West

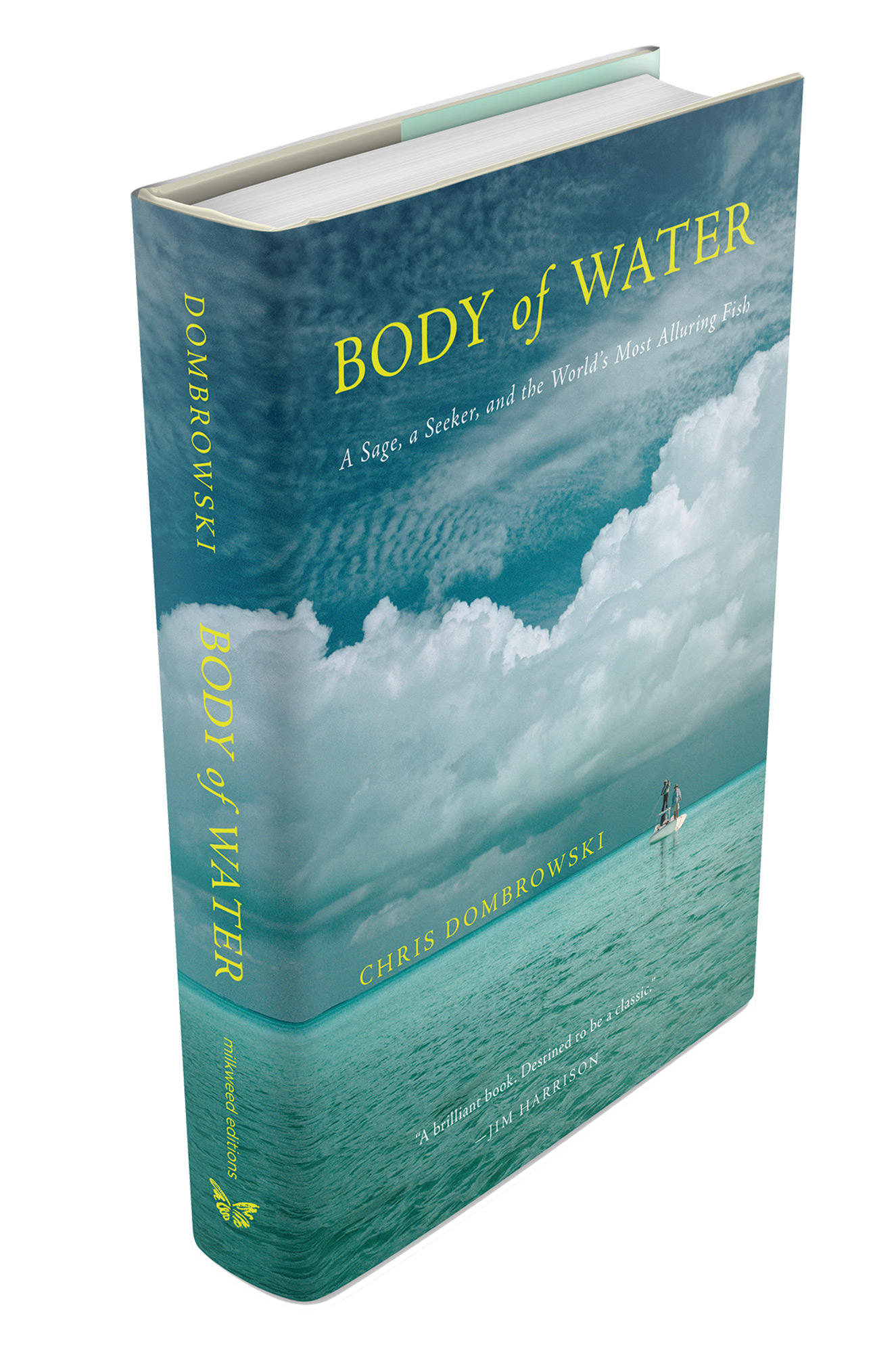

Sport fishing in the Bahamas, and in particular the sport of fly fishing for bonefish, is a huge industry that lures hundreds of fishing enthusiasts and millions of dollars to the Caribbean every year. Body of Water: A Sage, a Seeker, and the World’s Most Alluring Fish (Milkweed Editions, $24) is destined to take an iconic place in the literature of the bonefish. Chris Dombrowski rightfully has been heaped with praise for the beauty of his writing and the thoughtful, original nature of his musings in this new book. But while he celebrates the joy of the sport and the beauty of the water and surrounding land, he also — rightfully — laments the changes that the explosion of the sport has brought to McLean’s Town in the Bahamas, and to the lives of the people who live there. Perhaps it is appropriate that this book, which quests to tell a fundamental story of integrity in the face of overwhelming odds, explores the ironies and big questions of life. And when it inevitably draws more people to experience the place and hopefully ask the same questions, maybe that can be a good thing, too.

Part memoir, part biography, part travelogue, part fishing guide tell-all, Body of Water reveals what happens when Dombrowski, a Midwestern transplant turned Missoula poet, writer, and fishing guide — in the middle of a very stressful time — gets a life-changing email saying, “Can’t go, it’s all paid for, just book a flight to Miami.” Dombrowski leaps at the chance and is pulled into the world of legendary fishing guide David Pinder, his multiple descendants, the Deep Water Cay Club, the sport of bonefishing, and away from a late winter spiral of depression and worry over trying to raise a family on a fishing guide and poet’s salaries.

The book, which Dombrowski describes as creative nonfiction, is gorgeously, lyrically written. An interest in sport fishing, and bonefishing in particular, is not required for a reader to be drawn into the descriptions of shallow blue water, sightings of the elusive fish, the grace and beauty of a cast by an expert, and the excellent conch salad at Alma’s restaurant. Dombrowski’s well-informed curiosity and interest in the guides, the industry, and the fishing life — even more than the fishing itself — pulls the reader into the story of Pinder’s life and pulls Dombrowski out of his depression as he soaks in the wisdom of the older man and his story of finding happiness as a fishing guide.

The story of bonefishing and the Deep Water Cay Club is fascinating. Bonefish aren’t coveted for food — locals eat them, but the effort is generally considered not worth the reward — and they aren’t particularly gorgeous fish, especially compared to tarpon and other trophy species. But they are fast and elusive 20-pound flashes of silver, and evidently extremely challenging to catch. In the late 1950s, sport fishing in the Bahamas really took off, largely due to David Pinder and the Deep Water Cay Club.

When Dombrowski met Pinder, he was retired and had already spent the tiny pension given him by the resort he’d spent his life working for. He was living in a shack on the island and suffering from cataracts, but still fishing and watching his son and grandson do the same. The patience and careful watching required of a guide who is hired to pole into the shallows and spot bonefish at a price of more than $700 a day is a set of skills that doesn’t change generationally, though what the young guides choose to do with their $100 tips does, and the demands of their visitors do. Dombrowski interweaves his own experience as a guide with his experience in the Bahamas, providing an effective contrast but also a rueful acknowledgment that guiding — and gossip and petty infighting and politics and economics — has a lot of universal themes associated with it. And even more than the often incredibly moving and wise words that Dombrowski gleans from his Bahamian hosts, those very human moments linger. The times when a guide faces a huge loss when a distracted boater with a cell phone T-bones the guide’s boat and means of livelihood, when a grandson of David Pinder is more interested in the screen in his hands than the rod and pole that are his birthright, or when Merv the guide says, “You love it down here, man. But it’s no paradise,” make this book tender, poignant, funny, and very well worth the effort.

Novelist and memoirist Pete Fromm’s life trajectory is not that different from Dombrowski’s, but he tells a very different story in another personal book — his second memoir — The Names of the Stars: A Life in the Wilds (Thomas Dunne, $25.99). A Wisconsin boy who made his way west to the University of Montana for a degree in wildlife biology, Fromm focused his first memoir, Indian Creek Chronicles, on the story of a winter he spent alone in a tent in Montana’s Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness at the age of 20. He left school to be a caretaker of salmon eggs that were being released into the area and went looking for a mountain man experience with all the enthusiasm of youth. This second book is again a story of spending weeks alone babysitting salmon eggs, this time in the legendary Bob Marshall Wilderness, but with more reluctance when his hope that he can take his young sons along with him into the field is dashed by liability concerns. But this book explores bigger themes: It’s about being in the moment even when you’re tugged at by other calls, how someone ends up where he does, and what, sometimes, he has to leave behind to get there.

Fromm’s first memoir was the story of a young man enamored with the tales of the mountain men and the romance of solitude, the foolhardiness of acting on a whim, and the fake-it-til-you-make-it bravado of youth. The second book tells the story of both the man who made that choice with only two decades of life experience, and the one two decades older who struggles with the idea of leaving his young family. Fromm carries his preoccupation with his small sons into the woods along with a deer hide from which he plans to make mountain man shirts as a surprise for them. When he opens his pack, Fromm is surprised and touched to find a napkin drawing by his older son (a neat reference to the drawings Fromm puts in their lunch boxes) and jiffy-pop popcorn packed by the younger one. Interspersing details of his early work for the Park Service as a lifeguard at Lake Meade, and then as a river guide in Grand Teton, his courtship of his wife, and his travels across the West, with the details of his stay in the Bob Marshall, this is a book about an older, wiser man written by an older, wiser man.

While Indian Creek Chronicles is arguably Fromm’s best-known work, he is an accomplished short story writer and novelist, and has the novelist’s knack for character development and plot. The danger when someone so gifted with words chooses to tell his or her own story is that the tools at his disposal makes it possible to write a more lyrical, beautiful tale by editing out or coloring details. But Fromm wins me over from his acknowledgements page, admitting that this is a book that is “about something” and not just a recounting of a life spent in the wild. While so many memoirs are just about an interesting life lived — or a life that the writer believes was interesting — this is a book about something. It’s about how important it is to stay true to yourself even as you are swept up as a parent in the lives of your children and in the responsibilities that go along with that. And it’s about accepting the destination that your life’s path has brought you to and embracing it gracefully, even when the worry and the longing creep in.

Fromm’s story isn’t about spending a whole winter in the wilderness, but just a few short weeks in early spring checking the eggs and watching the hatch — though he has a few memorable encounters with bears that recall his wife’s words arguing against taking their 6- and 9-year-old along on the adventure: “They’re snack sized.” It’s a story about learning new things about yourself and finding a different level of appreciation for life — and the epilogue makes it clear why. But this isn’t just a serious book. The horseback ride with the biologists, the cabin’s cold storage, and the details of life at the Fromm house in Great Falls, as well as those moments with the bears, make this an entertaining celebration of wilderness and family life.

The Earth is Weeping: The Epic Story of the Indian Wars for the American West by Peter Cozzens (Alfred A. Knopf, $35) is a monster of a book at 576 pages, with two dozen maps and a rich collection of archival images, but it is two tiny words in the title that capture the immediacy of this new book. The present-tense title offers a hint that this book, though covering a century and a half of history, is very much relevant in 21st century America. And the word “for” in the subtitle points out that these weren’t just the black-and-white struggles about American ideals that have been portrayed as stereotypes in our pop culture and even in history books for the last century. These were battles for territory and for dominance between fully formed cultures, not without nuance on all sides.

Divided into four broadly thematic but also chronological sections, Cozzens’ book offers a comprehensive look at the so-called “Indian Wars” in the American West that commenced as the Civil War raged in the East and concluded with the Lakota surrender on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota in 1891. The structure of the book allows the interweaving of timelines and historical context in a way that makes the heavy subject matter extremely readable and also thought provoking. Cozzens, who has written numerous books on the American West and the American Civil War, and who was a foreign service officer with the State Department, takes to heart his own words of warning about the myths that pervade pop culture, and the wide mood swings that have affected scholarly history over the last century and a half:

No epoch in American history, in fact, is more deeply steeped in myth than the era of the Indian Wars of the American West. For 125 years, much of both popular and academic history, film, and fiction has depicted the period as an absolute struggle between good and evil, reversing the roles of heroes and villains as necessary to accommodate a changing national conscience.

In relating the history of the Red Cloud’s war, when the recently victorious Civil War Major General William T. Sherman occupied the Bozeman Trail in 1866, Cozzens offers evidence that reveals a deep divide between the policies and ideals of the federal government and the men sent west to help open the frontier, as well as the settlers who were eager to gain a foothold there. He also offers a sophisticated view of Red Cloud’s position on the occupying forces, pointing out the fallacy of pretending to negotiate a peace while arming garrisons. And he offers the suggestion that Red Cloud might not have been eager to let the representatives of the “White Chief” steal land that the Oglalas — looking for richer hunting ground in the wake of depredations by encroaching settlers — had just wrested with great effort from the Crow. He further goes on to describe the warrior culture of the Indians and reveal their experience and success as fighters.

Cozzens also offers nuanced views of the actions and words of some of the most famous men involved with the eventual and inexorable decline of the great warrior bands of the West. His storytelling skill allows him to accept the various and evolving points of view of Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, Sherman, and men like Indian agent James McLaughlin, giving each a distinct characterization and not just a caricature.

Ultimately, this isn’t a book about a time period that has passed and been immortalized in museum dioramas — it’s about a continuing dialogue happening in America over culture, cultural conflict, and the inherent struggles between free people with free will in a land that idealizes individuality and pluralism but struggles to accommodate the complexity of those ideals. This is a history book, but it is also a present-tense book, full of ironies about how we’re not so different from 19th century Westerners.

The premise that the Indian Wars of the late 19th century were more than a necessary step in achieving America’s Manifest Destiny, or a one-sided conquering of one people by another, may not be original, but rarely has it had such a striking and thorough exploration.

OF NOTE:

Readers who have followed the career of painter, fly fisherman, and part-time private detective Sean Stranahan through his adventures in Keith McCafferty’s mystery series will welcome a chance to be reacquainted with Stranahan and Sheriff Martha Ettinger, and will meet new entertaining characters in the form of mermaid performers and sociopathic villains in Buffalo Jump Blues (Penguin, $26), the fifth volume in the series — and a book that’s more than just a mystery novel with a Montana setting. McCafferty, who is the survival and outdoor skills editor for Field & Stream and a Bozeman, Montana, resident, just won the Spur Award for Best Western Contemporary Novel for his previous book, Crazy Mountain Kiss, and he has once again created a cast of memorable characters and populated a believable and authentic, and still quirky and cinematic, Montana setting for them to inhabit. The politics, biology, and lore of the bison in the American West underpin this fast-paced tale of romance, murder, and intrigue, offering a good introduction to the subject while keeping you turning pages to find out what happens next in the hunt for justice and in the lives of his characters.

Paulette Jiles, poet, memoirist, and author of the bestselling novel Enemy Women, creates an incredible cast of characters and examines fundamental questions about civilization, family, and trust in News of the World (William Morrow, $22.99). The book gets its title from the livelihood of a septuagenarian Civil War veteran named Captain Kidd, who travels through northern Texas reading newspapers from the East Coast for audiences seeking news of the outside world. When he is offered a $50 reward to take a 10-year-old orphan girl south to San Antonio to reunite her with her family, he agrees. The difficulty is that the girl, Johanna, had been taken captive by the Kiowa four years earlier. She doesn’t remember English, refuses to wear shoes, and has no memory of the aunt and uncle she is being taken to join after her “rescue.” Jiles reveals her deft hand with dialogue and character, dipping into vernacular but not overusing it, diving into the inner worlds of the old man and the young girl without a heavy-handed reliance on gimmick or trope, making the story read like a family epic and the characters feel like real people. Her particular gift is taking the tropes and structures of the classic Western and making them feel modern.

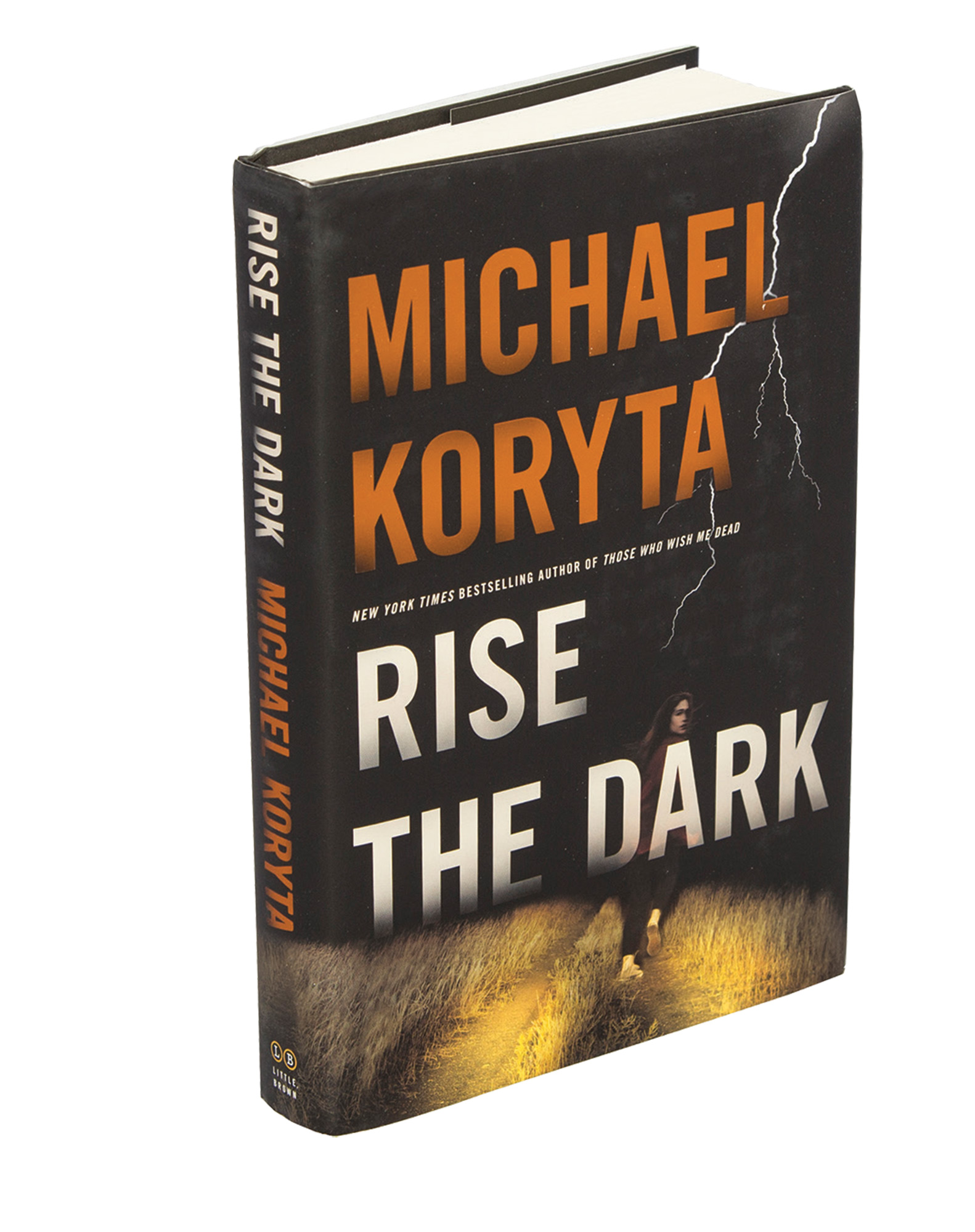

Rise the Dark (Little Brown, $26), the new mystery-thriller by Michael Koryta, takes readers on a satisfying hunt for justice that picks up after the investigation of the murder of Lauren Novak on a lonely Florida road. This story takes her husband, Markus Novak, the detective first introduced in Koryta’s previous book, Last Word, to Red Lodge, Montana, and into the world of high-voltage linesman and the last snows of winter in the mountains of Montana. “Rise the dark” were the last words that Lauren wrote in her notebook before her murder, but neither Markus nor any other investigator on the team knows what they mean. In the previous book in the series, Markus risked his career to try to identify the murderer. In this new volume, the man who he believes killed his wife is out of prison, and a strange set of circumstances leads to a kidnapping, possibly by Garland Webb, the man who has just been released. Koryta’s gift as a thriller writer are such that his dialogue, settings, and characters melt seamlessly into his smooth plots. You keep reading because the story demands it. The Montana setting and the unusual idea behind the blackout that leads to the conflict in this book help it rise to the top of must-read thrillers this season.

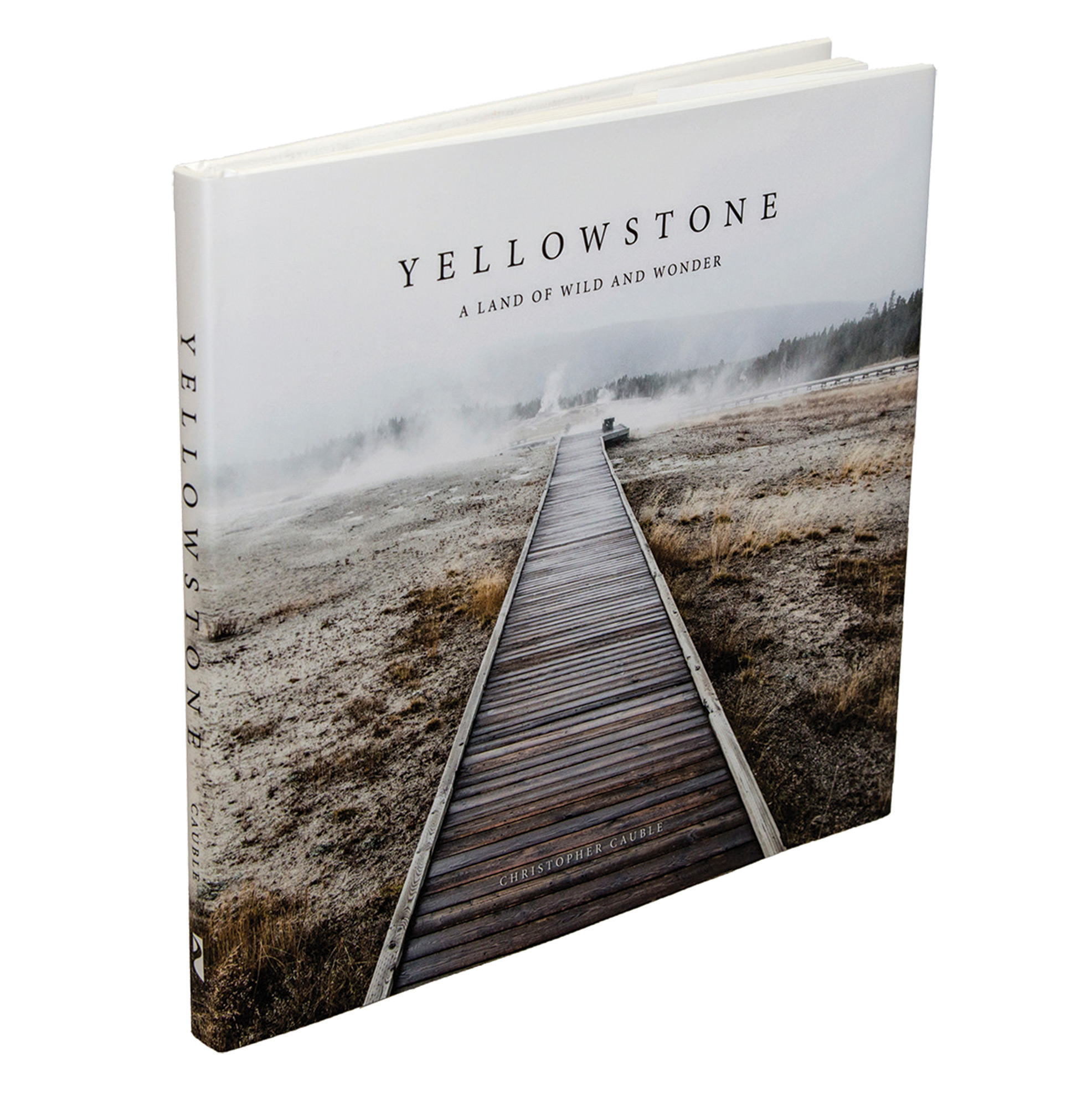

Yellowstone: A Land of Wild and Wonder (Riverbend, $29.95) by Christopher Cauble features an unlikely but very Yellowstone image on the front cover: the boardwalk at Old Faithful stretching straight into the distance, the frosted ground around it, the steam from the geyser basin not quite obscuring the view of the trees and mountains beyond. The colors are white and gray and almost gold, and they evoke a lesser-seen and lesser-known view of America’s first national park. Throughout the book, the photographs live up to the cover image. They are unusual, beautiful, and artistic (“The Old Faithful Inn and Geyser Under the Milky Way” would sell thousands as a poster), and for visitors who like to stray outside of the summer high season and the most-trafficked areas of the park, this is a refreshing collection as well. Wildflowers, wildlife, iconic views, and changing seasons are all well represented through the images and spare captions. There’s a quieter appreciation of the park in these pages than is often represented in the celebratory books and documentaries that pervade the genre. But this feels like the real park as revealed through eyes of affection.

No Comments