29 Jul Billy Schenck Rides Again

BILLY SCHENCK SPENT 33 SUMMERS in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, but when he was asked to come up with a painting for this year’s Fall Arts Festival, he found himself stumped.

“All the time I lived up there, I was never specifically inspired by the Tetons,” Schenck says from his studio in Santa Fe, New Mexico. “I’ve always said I only did four paintings of the Tetons when I was up there, and three of those were commissions. I actually did a few more than that, but not many. So I thought, ‘what am I going to do that would be Teton Valley-oriented and be good and significant to my style?’”

Schenck, you see, has always been drawn to desert colors — “my warm-tone pallet,” he calls it — more Maynard Dixon or Ernest Leonard Blumenschein than Charles M. Russell or Olaf Seltzer.

“But that was because I kept looking at the Tetons in the daytime,” he says. “They were always blue. It just never crossed my mind that in that first light in the morning — it’s about a five-minute window, actually less than that — they just go hot pink until the direct sunlight gets on them so it’s almost like desert colors. I thought, ‘There’s the answer.’”

Inspired by a photo he took of the Snake River Oxbow and a late 1920s pulp magazine cover of a cowboy crossing a river, Schenck came up with a 50-by-50 painting — Thirteen Minutes from Eternity — that serves as the poster for the 31st annual Fall Arts Festival, Sept. 10 to 20.

This is fitting, since Schenck did the festival’s first poster back in 1985, and was a driving force in getting the event started.

Of course, when Schenck, Dick Flood (who opened Jackson’s first gallery in 1963) and a few others proposed a fall art show, most residents thought they were crazy. Back then, art season ran from Memorial Day to Labor Day.

“Our thinking was there are plenty of people who are coming back to their dude ranches and second homes — wealthy people — who would have a more focused experience than when they had all their kids with them,” Schenck says. “And it worked. It really worked.”

Indeed, Altamira Fine Art’s executive director Mark D. Tarrant says, “the Fall Arts Festival has become one of the ‘must see’ events in the Western contemporary art world. The town will be sold out, with top collectors on the scene to peruse the galleries and auctions.”

Altamira will present Schenck’s one-man show Sept. 7 to 21, with a reception Sept. 16. Schenck will autograph festival posters, and the original will be auctioned off.

The festival will also showcase Schenck’s longevity, which Schenck concedes he practically “derailed” when he moved away from Western art.

Although he grew up in Wyoming, Schenck’s art leaned toward contemporary and European in the 1960s until he saw director Sergio Leone’s spaghetti Western movies — A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly — that made Clint Eastwood an international star, and reinvented Western filmmaking, not to mention Schenck’s portfolio.

Schenck learned to paint interpretations of Western cinematic material. “I knew instantly I was going to put a new face on Western art,” he says. “Nobody had made Western paintings coming from the angle that I had.”

Inspired by Andy Warhol, with whom Schenck worked with briefly in 1966, Schenck became a star. He was contemporary Western, Southwestern Pop and on the fringe of Photorealism. He had his first solo show in New York in 1971, found representation in Brussels, Zurich, Paris, London … and then ….

“Just as quickly as I rose to fame, it faded away,” he recalls. “By ’74, ’75, I was struggling to make a living again.”

He left New York and returned to Wyoming, splitting time painting outside of Jackson and in Phoenix, Arizona. In 1997, he moved to Santa Fe, put aside paintbrushes and turned to photography.

“I thought I was done painting Western,” he says.

But when a client in France commissioned Schenck for three movie paintings in 2009, Schenck came galloping back to the Western world. He hasn’t slowed down since.

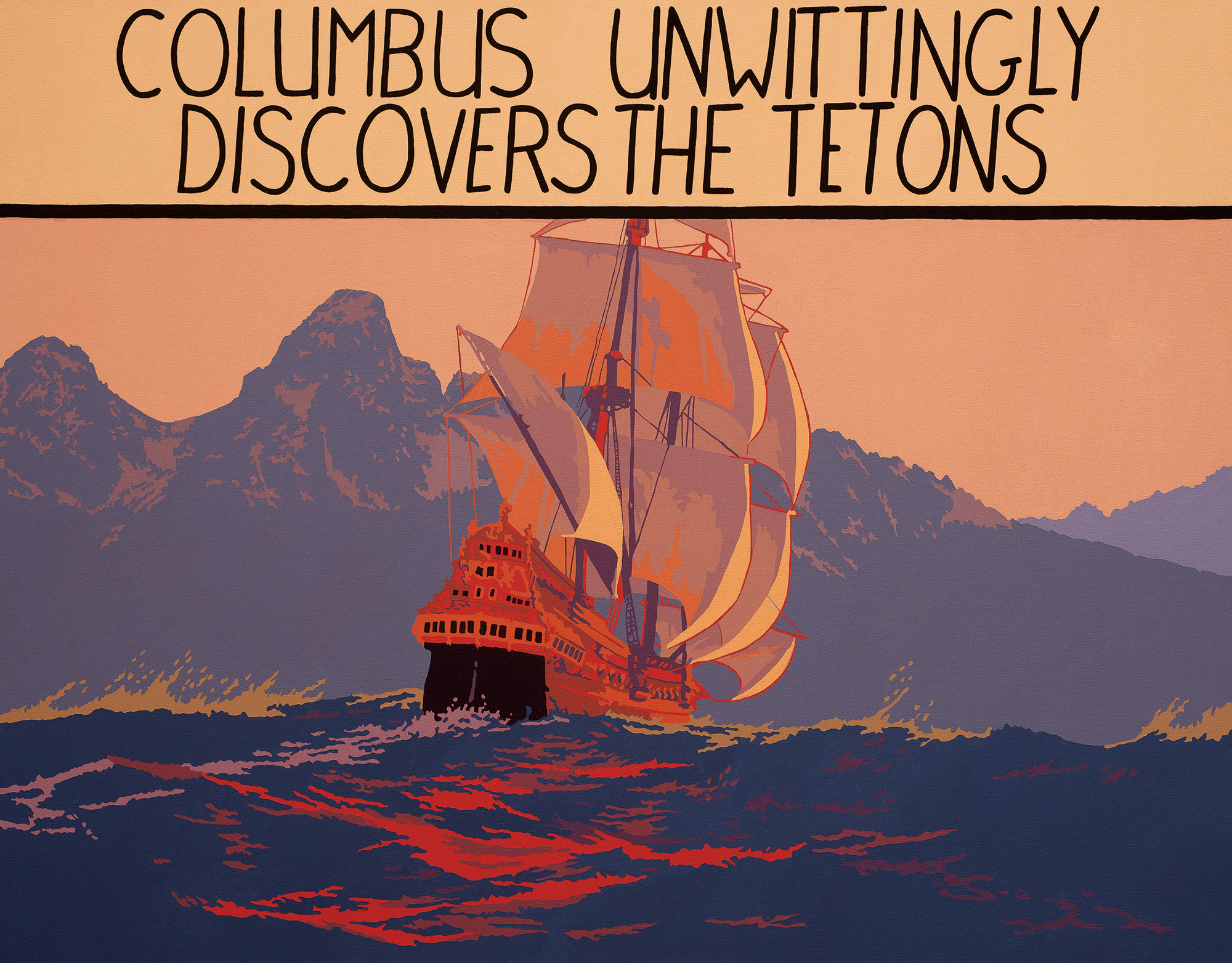

Tarrant is drawn to Schenck’s “con- temporary treatment of the myths, images and attitudes of Western Americana. I enjoy his ‘punk cowgirl’ series,” he says, “the edgy and irrelevant caption paintings, the breathtaking treatments of classic landscapes, and recently something brand new: He began a ‘dot painting’ series, which is very hip.”

He’s not alone.

Schenck’s work can be found in 48 museums. Where he once averaged two or three solo shows a year, this year will find him doing more than a dozen. He’ll be one of the headliners when Western Heroes of Pulp Fiction: Dime Novel to Pop Culture opens at the Tucson (Arizona) Museum of Art on Oct. 24.

Not that he ever dreamed of such success back when he was spending his summers in Jackson.

“That’s a dangerous way to think,” he says, adding with a laugh: “Maybe, on rare occasions, if you were sitting in a bar with your buddies after a rodeo and you’d had six or eight beers, you might venture the thought with some bravado. But, boy, you’d better sure forget about it the next morning.”

Today, he finds inspiration in his photographs and old paintings, pulp magazines, the art of Dixon, Ed Mell and the Taos masters, as well as all those Western movies he likes to watch.

And while he says he doesn’t miss Jackson — “except for when I’m there” — he looks forward to returning in September.

“One thing I still connect with,” he says. “I collect antique ranch furniture, most specifically Thomas Molesworth’s. In the western corner of Wyoming, that was their artistic heritage. That’s where truly high-end ranch furniture was invented. That’s always exciting for me. When I go up there, I’ll be taking my trailer again.

“Going to Jackson Hole keeps me broke. Really broke.”

- “The Trail to Dripping Springs” | Oil on Canvas | 40” x 40”

- “The Mighty Mesa” | Oil on Canvas | 40” x 70”

- “Day of the Dead” | Oil on Canvas | 40” x 80”

- “The Decision” | Oil on canvas | 20” x 24”

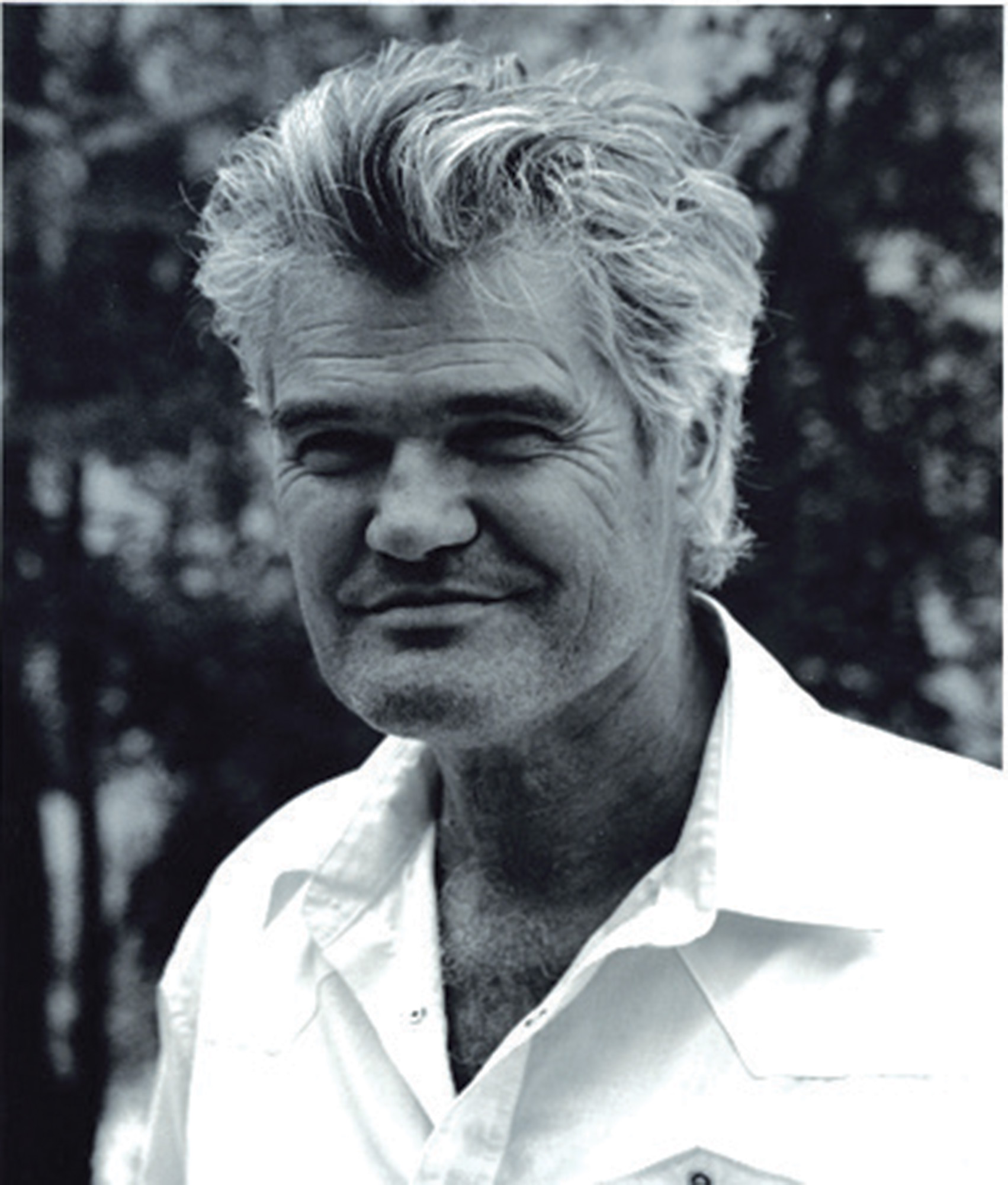

- Artist Billy Schenck at his Santa Fe, New Mexico studio

- “Columbus Discovers the Tetons” | Oil on Canvas | 35” x 45”

- “Thirteen Minutes to Eternity” | Oil on Canvas | 50” x 50”

No Comments