29 May Behind the Chutes

The World-Famous Miles City Bucking Horse Sale is the social event of the year for the small town of Miles City, Montana. For over seven decades, this one-of-a-kind sale weekend has showcased horse races, professional saddle-bronc riding, calcuttas, mutton bustin’ for the kids, live music downtown, a morning parade, and an extensive trade show featuring a wide variety of shopping and service vendors. The bucking horse sale itself is a live auction that attracts prospective buyers from all over the country, and the event returned with all its fervor May 15 through 18, 2025, kicking off the rodeo season in the Treasure State. In fact, Montana recently adopted American rodeo as the official state sport, honoring the region’s cowboy heritage.

Most riders have custom gear specially crafted and personalized to their taste and life. Pictured are custom hand-tooled leather chaps, symbolizing sentimental family values that the cowboy carries every time he rides.

The bucking horse sale comes at an exciting time in Montana. After a long winter, the sun finally emerges, and a new season of rodeo begins. Typically, the sale weekend is one of the first opportunities for a cowboy to don a straw cowboy hat in exchange for winter’s warmer felt version. In the lines of spectators, competitors, and chute crews, a sea of light-colored straw hats spreads out in all directions.

Chute boss Ty Linger bows his head in prayer and places his hat on his chest before the show begins.

As attractive as it is dangerous, saddle-bronc riding is a classic event in the sport of rodeo. Every time a rider sets down into the saddle, there is great risk and reward. The chute gate swings open, and the bronc fires off into the open arena like an explosion. The adrenaline is unmatched. Riders often attest that the feeling they experience at the end of a clean ride — following a safe landing in the dirt as the whole crowd gives a standing ovation — is enough to drive any cowboy to the chase.

An integral part of rodeo, the pickup men are often unsung heroes. These guys wait on horseback in the sidelines, on call to bring a rider to safety and quell a bucking horse at the end of each ride. With deft precision, they bring their mounts up to speed with the bronc, help the rider dismount, unbuckle the flank strap, and move the bucking horse out of the arena. Without them, rough-stock riding events wouldn’t be nearly as smooth or safe. Two are mandatory to share the workload, and many pickup men train their own horses, working with them intimately and extensively so as to be able to maneuver in the most proactive and timely manner.

The scoring of a bronc ride includes both horse and rider. The horse is scored on the front-end drop and the height of the kick, while the rider is scored on mark out (feet to shoulder position), outward toe point, and overall rhythmic control of the ride while holding their free hand outward.

“A pickup man is no better than his horse,” says K.C. Verhelst, who serves in the role for Miles City. The last to give himself credit for the outstanding pickup work he has done and continues to do, Verhelst humbly tips his hat to his horse.

Top-ranking broncs easily buck at heights that bring their hoof tips as far as 4 feet above a pickup man’s head as he rides into position beside the bucking horse for the rider to reach out for a swift, assisted dismount. Pickup men put themselves in the line of danger to help a rider out of it. For them, the risk of getting kicked by a bucking bronc is enormous, which makes each move they make all the more crucial.

Back numbers are assigned based on season earnings and help in the organization of rodeo contestants while representing a rodeo professional’s career achievements. The lower the number, the higher the amount the rider has won, ranking them in each event throughout the regular season.

Jay Shaw has been a pickup man for 30 years, and he’s been picking up at Miles City’s sale for over 18. His father was a pickup man as well; at just 14 years old, Shaw got an early start following in his footsteps. Shaw and his wife, Edyna, live just north of Miles City and are as familiar with the territory as it gets. When asked what sets Miles City apart from other rodeos, Shaw says, “It’s probably the number of horses we go after in one day, as well as the variety of bucking horses. Getting to work with great guys makes my job easier and more fun, and having the same goals and good communication makes for the best possible work out there.”

Spectators watch all the action and revel in the family environment of the grandstands.

Just as an orchestra needs a conductor or a football team needs a quarterback, a rodeo needs a chute boss. Ty Linger, a third-generation chute boss for the sale, holds a specific responsibility in keeping everything moving smoothly and on schedule: He makes sure everyone is in the right place at the right time and that each bucking horse is released in the correct order. Through this work, Linger has developed many connections with the guys involved in rodeo, and he’s been a mentor for young riders who have grown and come to succeed in their rodeo careers. “The friendships mean so much in rodeo, but in this position for me, it’s a good thing when they’re a little scared of me, too,” Linger says with a chuckle.

A cowboy out of the small town of Jordan, Montana, Connor Murnion, age 26, rides bucking broncs and bulls all summer long.

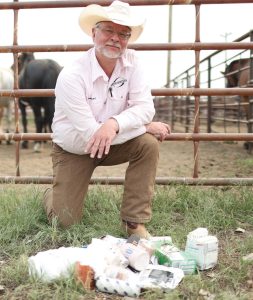

Phil Solum comes to the chutes bearing medical supplies in preparation for injured cowboys. With over three decades in rodeo doctor experience, Solum understands his patients’ toughness and grit.

“Some horses have a different bucking pattern,” he says, adding that a successful ride requires adaptability in the moment. “For the most part, you gotta get in there and lift your hand and do your job and be prepared for anything to happen.”

One of the top saddle-bronc riders in the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association circuit is Dawson Hay. He’s a name to look out for this season and in the coming years. Hay started riding broncs when he was 15 but says he didn’t take it seriously enough for it to be his profession until he was 18, when he realized his skill set was better suited to riding broncs than bulls.

A Superman handstand landing may be the result of a bronc’s hard launch. Walking out of the arena without injury is never promised or taken for granted.

Hay describes the Miles City sale as one of the best rodeos of the season, as far as bronc matches go. His goal is to finish the year as one of the top five bronc riders in the world, which is dependent on his ability to ride whatever bucking horse he is assigned.

At each rodeo, riders draw for their bronc. “In order to win the long rounds, the draw of the bronc is definitely a huge deal,” Hay says. “You can make a lot of horses work well for you, just depending on how you’re riding, but the draw is a big part. The top guys seem to make it work on everything they draw.”

As any bronc ride can turn disastrous on a dime, event organizers have to be prepared for anything. Phil Solum is a rodeo doctor who has been aiding injured competitors since 1988. He arrives dressed in Wrangler jeans and a pearl-snap shirt, blending in with the rest of the cowboys along the arena fence. His job requires that he have the ability to assess a situation and quickly identify a rider’s injury type and severity. He’s equipped with a single large duffel bag full of supplies to treat his patients. Riders come with different levels of experience, and the horses all possess different traits. “Life is a calculated risk,” Solum says knowingly. “You get out in this arena with a 2,000-pound animal trying to get you off its back; things happen.”

Reliable gear plays a heavy role in the quality of a ride; a riggin is a hand-held piece made of leather and rawhide that mimics the feel of a saddle horn and assists the rider in finding a center of balance on the horse.

Solum enjoys the entirely different kind of mentality that is rodeo culture. “The one thing about rodeo people in general … they’re stubborn, but they accept the risk and don’t blame anyone for it.”

In the Western world, an elite athlete is generally measured by the time, sweat, blood, and grit they put into their endeavors, and a huge part of it for rodeo stars is the intense mental work each competitor faces internally. What they do before, during, and after the ride does the talking for them.

All eyes fixed on this flighty bronc as it exploded out of the chute. Hundreds of bucking horses go through these gates every year in Miles City, and many of them qualify as top-ranking athletes bred specifically to do one job: buck well and buck hard.

A wide variety of spectators flock to the grandstands and arena fence lines at Miles City’s rodeo grounds to witness the inspiring courage, heart, and athleticism of the cowboys and horses alike. The diverse crowd can yield poignant conversations as people stand shoulder to shoulder, attention fixed on the arena. An older cowboy with well-worn garments might know everyone’s names, the names of their fathers, and even the names of the horses in the arena and behind the chutes. He might point out riders in the arena, saying, “I used to ride broncs with his dad in the ’80s!” The next person down could be attending a rodeo for the first time, taking the action in, and consumed by questions.

All the traditional Western fanfare, rodeo events, and intoxicating energy make the Miles City sale an event in its own category, and the genuine, hardworking folks behind the scenes make it all possible. In eastern Montana, there’s always more in the wide-open landscapes and small-town communities than meets the eye. The stories, connections, and roads amble on for miles, like the World-Famous Bucking Horse Sale namesake itself — Miles City.

Elizabeth “Liz” Jobe is a freelance writer and artist with a bachelor’s degree in writing from Montana State University. She was born and raised on the Climbing Arrow Ranch outside of Bozeman, Montana. Today, she and her husband tend cattle, keeping tradition alive while raising their 1-year-old daughter in southwestern Montana.

Melanie Maganias loves capturing the essence of her subject matter in editorial assignments, at weddings, and in portraits by following her intuition and using her camera as a tool to depict her vision. Named one of America’s Top 15 Wedding Photographers by PDN, her work has been featured in The New York Times, Forbes, Real Simple Weddings, Martha Stewart Weddings, and many other publications. She earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in photography and has also taught at Montana State University.

No Comments