15 Jul Images of the West: Authentic Artist Will James [1892-1942]

THERE’S SOMETHING ABOUT COWBOYING THAT attracts storytellers. Louis L’amour or Lash LaRue, Howard Hawks or Henry Fonda, our notions of what it means to live a life on the range have largely come courtesy of novelists, directors, actors, those interested in cowboys first as a device, a vehicle for their yarns. They need good guys and bad guys, life lessons, a lady in distress, a hero that triumphs over adversity. And these conditions, alas, don’t necessarily reflect the sweaty, dusty reality of a hard day spent with cattle.

Through this lens, it’s striking (but not especially surprising) how often the mythmakers have fictionalized even themselves. Ned Buntline was a pen name for Edward Zane Carroll Judson. The prolific Max Brand was born Frederick Schiller Faust. Owen Wister was a Harvard-educated lawyer from Philadelphia while Zane Grey had his start as a dentist in Ohio. Then of course there’s that paragon of cowboyism, John Wayne. His real name was Marion Morrison.

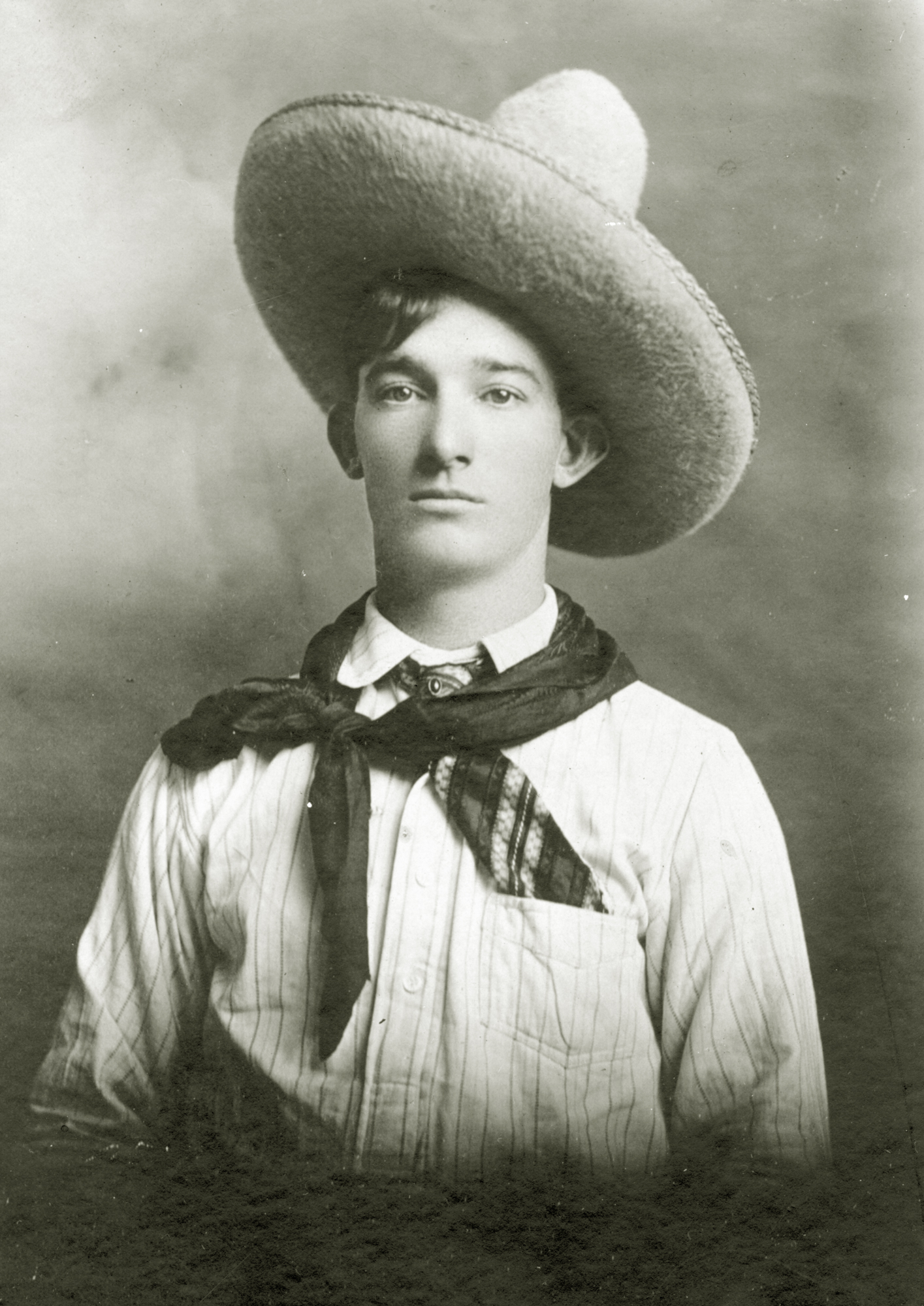

In this context, the Western artist and writer Will James — who was born in Montreal as Joseph Ernest Nephtali Dufault — is perhaps the finest cowboy we got. By all accounts an exceptional bronc skinner, a top hand, a man who could rope and ride with the best of them, he was also superbly gifted in translating that life onto the page. He broke mustangs, he ran his own spread east of Billings, he wrote and illustrated at least 24 books about cowboying, and the greatest fiction he ever told was the story of his own life. Searching for an ideal American cowpuncher, you could start and stop right here, with this French-Canadian embodiment of talent and tragedy, a man who pulled himself up by his own mythological bootstraps only to finally drink himself into the ground.

In 1907, an innkeeper’s son named Ernest Dufault boarded a train west from Montreal. He was 15. Raised on a diet of pulp novels and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, his eyes were starry for the life of a cowboy. Maybe he would find it in Saskatchewan. A few years later, though, Ernest got into some bad trouble (possibly a knife fight in a saloon), and headed south ahead of the Mounties, crossing over into Montana. Somewhere along the way, he changed his name to William R. James. Abe Hays, noted authority on James’s life and work, believes the name change came primarily as a way to avoid prejudice, to change James’s ethnic identity. “When he went west, he was a French-Canadian among Anglos and cowboys. He was no doubt the object of great prejudice.” For a kid who wanted to be a cowboy, “Dufault” wouldn’t do. He needed a new handle.

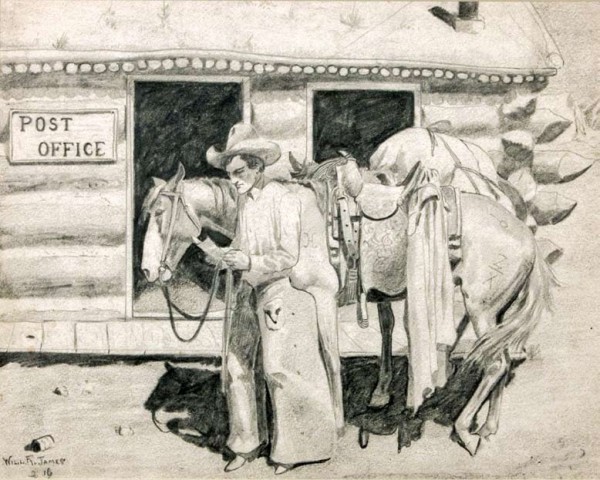

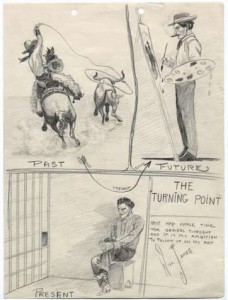

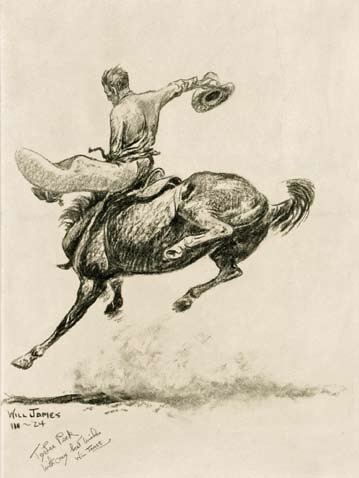

Will James cowboyed his way from Montana down to Nevada until, in 1914, he found trouble again. He was arrested for horse rustling, and sentenced to 12 to 18 months in prison. Even as a child he’d drawn compulsively, and he continued this habit in prison. There’s an interesting pencil sketch from the period, a quick piece he made by way of appeal to his judge. (“Have had ample time for serious thought and it is my ambition to follow up on my art.”)

After his release and a few more years of rambling, some time spent in the army during WWI, James began pursuing his career in earnest. He illustrated the cover of a rodeo program in the summer of 1919, and that fall, enrolled in the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco. It didn’t last long. James wrote, “I seldom went, and when I did I’d be drawing a steer, a horse or a cowboy instead of the clay and life models I was supposed to copy. I could never copy.” According to Abe Hays, the artist Maynard Dixon “told James to get the hell out of art school because it wasn’t helping him. James was already so far advanced in his life studies.”

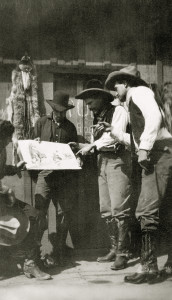

But Dixon and other friends in San Francisco helped James with contacts and introductions, springboarding him into the next decade. These years, 1920 to 1930, were effectively both the foundation and the apogee of James’s career. By 1922 he was publishing in Scribner’s Magazine, and in 1924 his first collection of stories, Cowboys North and South, was published by Scribner. His editor there was the legendary Maxwell Perkins. “Perkins was the major great influence on James’s literary life,” Abe Hays said. “If Perkins hadn’t found him, I think he would have just been a short story writer and perhaps spent more time on his art. Perkins turned him into a novelist.”

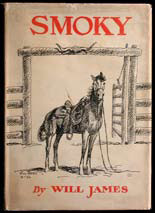

James’s first novel was the children’s book Smoky the Cowhorse. The story of a friendship between a horse and his cowboy, it won the Newbery Award, and inspired at least two film adaptations. James’s other marquee work, his “autobiography” Lone Cowboy, was published in 1930. James was 38, and for the previous 20 years or so had managed to keep his Québécois roots a secret; not even his wife knew his real name. Having painted himself into this corner, one can imagine that he had no real choice but to continue in the same vein, elaborating on his first deceits. The latter half of the book is relatively honest, but the descriptions of his early life are almost completely fabricated, albeit impressive in their detail. According to James, he had a mother who died of the flu when James was an infant and a father who was gored by a steer when James was 4. A French-Canadian trapper named Jean-Beaupré, or “Bopy,” took over the raising of him. These stretchers were so widely accepted that, as recently as 1978, a respected biography of Maxwell Perkins described Will James as having been orphaned early and taken in by an old trapper. (After James’s death, the probate court found the name Ernest Dufault in James’s will, pulling the first thread on what came to be a larger unraveling.)

The years after Lone Cowboy saw a decline in James’s life and work. His drinking gained momentum, and his wife left him in 1933. He had to sell his beloved Rocking-R ranch on Pryor Creek, east of Billings. Tom Decker, James expert and board member of the Will James Society, said, “After 1929 he would do some wonderful work, and then do some work of less quality, although he would have sober periods where he would do his usual great stuff.” After selling his ranch, James moved to a house under the rims in Billings, with just enough pasture to keep two of his favorite horses. He lived there alone. In 1942, in Hollywood, he died of kidney and liver failure due to alcoholism.

Creator of as many as 1,500 drawings, 40 or 50 oils, and a handful of watercolors, 70 years after his death Will James is still widely read (the Will James Society distributes his books gratis to schools, libraries and the armed forces), still greatly admired as an artist, still an influence. “Will James had a tremendous effect on people’s lives,” Tom Decker said. “Mine, for instance. There are tons of people with a little cowboy in them, and they are just as affected by his work. My brother handed me Lone Cowboy when I was young, and I couldn’t put it down. It nailed me. When you think you’re a cowboy yourself, when you read his writings, you know you’re getting the truth from somebody who really knows. And then his drawings are so absolutely on.”

Thomas Nygard, of the Nygard Gallery in Bozeman, Mont., said, “The guy lived and knew the cowboy life. There wasn’t a cell in James’s body that didn’t reek of the term cowboy. Better than anybody else in existence.”

And that finally, I think, explains the enduring appeal of Will James. For my tastes, I’m not sure that his writing has aged especially well. His colorful vernacular seems a little anachronistic, his style a little self-conscious. And while his drawings still jump off the page, still come alive with what the painter and sculptor Harry Jackson called his “miraculous, energy-packed line,” they remain primarily illustrations. Taken together, however, his stories and art reflect the rarest kind of sensibility. Hat brim to bootheels, James was a true cowboy, which is a rare thing. And if one of the foundations of art is authenticity, maybe it’s the only thing.

No Comments