20 Aug Artist of the West: Ensnared in the Human Form

MIDDLE OF THE ROOM, LIKE A BEACON, AWAITING THE NEXT STEP IN THE BRONZING PROCESS. This foray into forged materials is not new to sculptor Gabriel Kulka, but it is rare. His intentionally elongated figures unwind a fundamental intensity, the experience, not only of being human, but of being pulled into humanity as through a small keyhole of desire — leaving the marks of the journey like tattoos upon the anatomy.

“I call them robots but they’re not robots, they’re not marionettes and I don’t want to call them dolls,” he says. “I like to think of them as mechanical, although they’re not mechanical at all.”

Whether the figures are 4 feet tall or 2 inches high, Kulka’s sculptural perspective, a subterranean veined mapping of experiential shadings, reverberates with the vacant echoes of isolation — what it means to be ensnared in the human form.

“There are two very different things I work on in my head when I’m doing these,” he says, removing the damp cloth from the ever so tiny head at the top of the sculpture. “First, I’ll do a large-scale sketch on butcher paper. And that’s when I try to ‘unknow’ everything I knew before I started — and that’s vital. At the halfway point I reinvent the whole thing.”

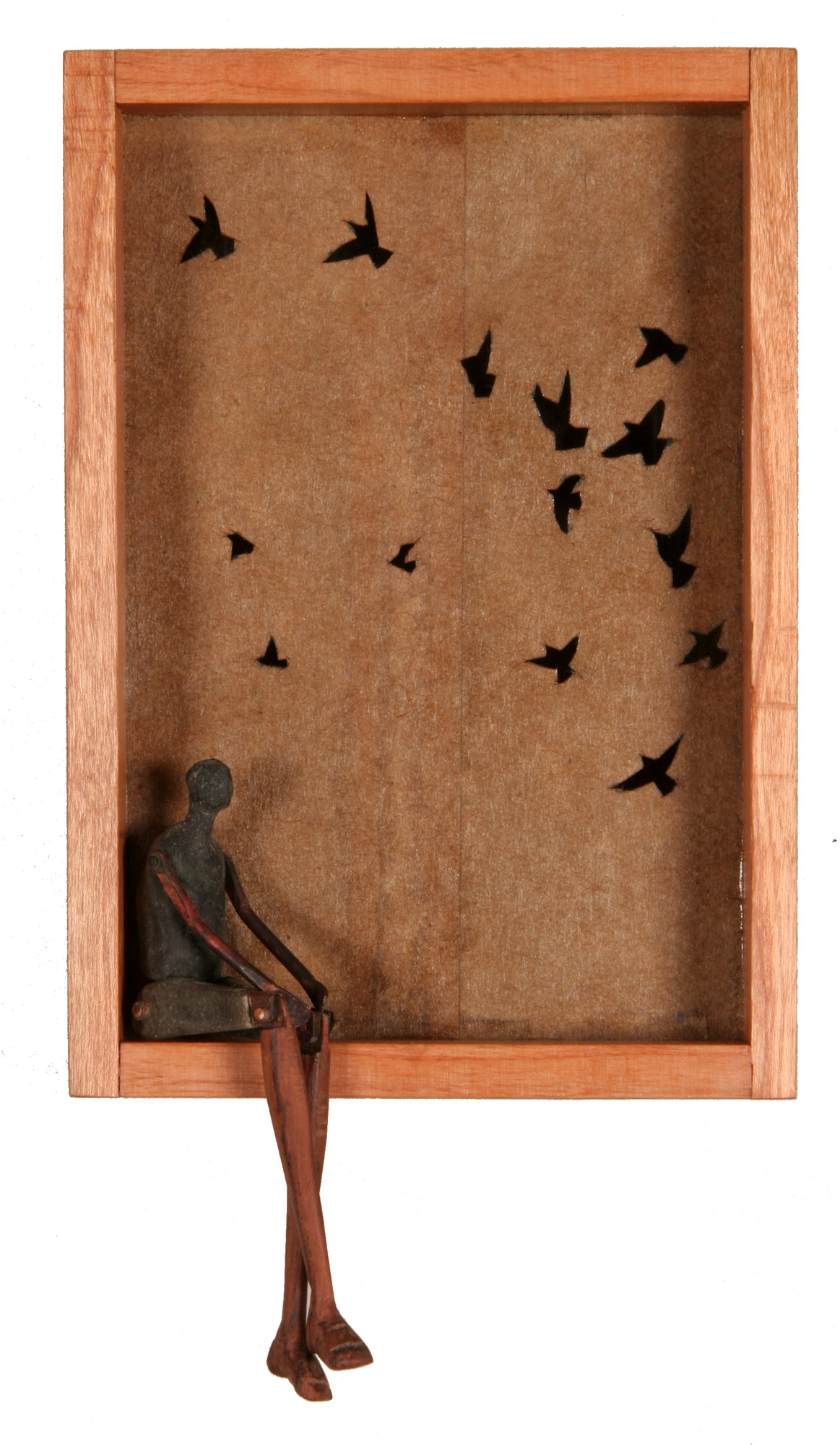

But these stand-alone pieces are only one type of the sculptures he plays with. Along the far wall of his studio/living space hang boxes with small moveable pieces within them. Each one, not more than 12 inches high, containing various found and made objects — wrapped string a

round small rocks, tiny paper airplanes, old fabric-wrapped electrical cords — usually includes one or more of his impossibly delicate figures made from wood, bronze or clay, with shiftable appendages. Every one lives in its own environment. And when seen together make up a kind of Hieronymus Bosch series of the seven deadly sins, if the sins were not lust but longing, not gluttony but self-denial, not sloth but surrender.

As he rewraps the clay in the damp, thin linen to keep it malleable, the idea for another piece — a figure wrapped in rough fabric, no face, just a head angling up from a long, long neck like an unbloomed flower seeking the sun — seeps into his head.

“Every time I work on a single piece I get at least 10 good solutions to a particular problem,” he says, his hands busy with the fabric. “Most people edit out nine and use one. But if I can keep them in my head, I can end up with 10 different pieces.”

Wires, tiny drill bits, a tin of furry pussy willow buds, vellum, string, and a couple of hourglasses complete with waiting sand, crowd one corner of his table; so many seemingly unrelated items on his workbench it is hard to imagine a single thing coming from it. But with Kulka’s constantly churning mind, there is the possibility of an army of wild-hand, invention-like creatures taking over the space.

“When I look at my work I see it in terms of architectural forms and I treat them like that,” he says, framing a head for the mold he’s making. Each piece of the large robot will need to be molded in order to create the bronze. “None of my figures are about people, I think of them in a removed state of being human, so it becomes a secondary distillation, based on something that’s already made.”

He compares it to Egyptian statuaries.

“I like the idea of human forms handled by humans,” he says. “You end up with two layers of human interaction.”

Anna Visscher, owner of the Tart gallery in Bozeman, Mont., will be showing Kulka’s work August 13 – September 8.

“When I first saw his work I was blown away,” she says. “I hadn’t seen art that I wanted to own so desperately in a long time. His work draws me in, it has stories inside of it, a little bit dark, a little bit twisted and very compelling. I just want to take them home and love them.”

One of the advantages of owning a gallery is watching people’s reactions to the artwork. Much of Kulka’s work invites the viewer to handle it — to twist a string, move a leg, turn or remove a part of the sculpture — there is the toy-like relationship with some of his pieces.

“I watch people reach out and interact with his work and I love that he encourages that in his pieces,” Visscher says. “His craftsmanship is so meticulous. It looks effortless but I know how long it takes to get it to where it is. We’re so surrounded all the time with the shiny newness of things that I think people are drawn to his work because it feels like it has its own history … they’re drawn to things like buttons and old typewriters and Gabriel’s work. I watch people have that experience … there’s this look people get when they’re experiencing it. His work is spiritual, not religious. There’s a reverence in there.”

Some of his figure pieces include hinged faces that open to a string filled space. Some have propeller/wings instead of arms. Maybe there is an old telephone dial to turn or a string to pull.

“Handling objects is huge for humans,” Kulka says, mixing up a batch of plaster for his mold. “It’s not just about the experience … it’s more about the way we absorb information. Our first compulsion is to touch a thing and to take that away is ridiculous. What I’m doing with the moveable pieces is more of an exchange of information and the kind of relationship I’m aspiring toward. A lot of my interest is in what a person brings to the table — it creates a symbiosis for my audience.”

As Kulka fusses about on his robot sculpture, he notes that he’s become interested in the idea of putting “dresses” on his figures. It seems most of his larger robot pieces tend to the female figure and his smaller figures that show up in the hanging boxes tend toward a simpler male-like figure. Unfurled white butcher paper thumb-tacked to the walls behind him show charcoal drawings of the robots — the first step in his process of creating these sculptures. Around the middle is a conical shape — a skirt-like object — Kulka likes it because it symbolizes both concealment and protection.

“On this one, I may do two different heads that can be interchanged,” he says, molding one head and mulling over the idea of molding a second one.

Although the robot is being cast in bronze that doesn’t preclude Kulka’s inclination to have a piece that can be played with, moved, altered.

“Lately, I’ve been obsessed with little paper airplanes,” he says, pointing to a few pieces where the paper jets play a part in the environment. “It goes back to my interest in how we put ourselves into the objects around us, how we emotionalize objects. It’s a prosthetic thing. I’m always trying to fulfill that experience when a thing is looked at and touched … a whole other process takes place there.”

Mary Lee Larison, co-owner of the Turman Larison Contemporary gallery, in Helena, Mont., said the first time she saw Kulka’s work was in another artist’s home.

“Even though it was a very small piece it was arresting,” Larison says. “And that’s how I would describe much of his work.”

Shortly after seeing that sculpture, Larison contacted Kulka about representing him.

“Every time I see his work, the same kinds of things are evoked in me — it makes me feel as if I were a child again, very vulnerable,” Larison says. “Even though some people think of them as dark, for me they’re comforting. It makes me want to touch them and spend time with them. It feels like they speak to me, personally.”

It is Kulka’s ability to speak in a universal yet extremely personal language that makes his work so accessible.

“He transforms these found objects into something so magical,” Larison says. “It reminds me of the literary work of Isabel Allende and Gabriel Garcia Marquez, with that kind of magic realism, I expect his sculptures to come to life. There’s a narrative that runs through the pieces as well as a melancholy mystery. I have a background in theater so they speak to my theatrical self. They have their own stages. They’re innovative and beautiful. He doesn’t doctor the original pieces, they’re transparent as to what they are and where they came from and that’s satisfying.”

Larison appreciates Kulka’s design judgment.

“I love the scale he uses,” she says. “And I know that he could make choices and include a lot more material, but he has a sense of what to leave out.”

In his small work space, Kulka bends over his sculpture, painstakingly rolling a piece of clay in his hands. Even though he is only creating the structure for the mold, everything he does he does with purpose and forethought. Every aspect of his work carries with it the complicated arguments of content and complexity.

Yet there is also an openness to his work, a kind of exposure to our deepest fears and desires, that, as humans, we seldom allow ourselves to breach. By observing these aspects of our nature, by examining our personal wilderness through Kulka’s sculptures, perhaps we can find a way home.

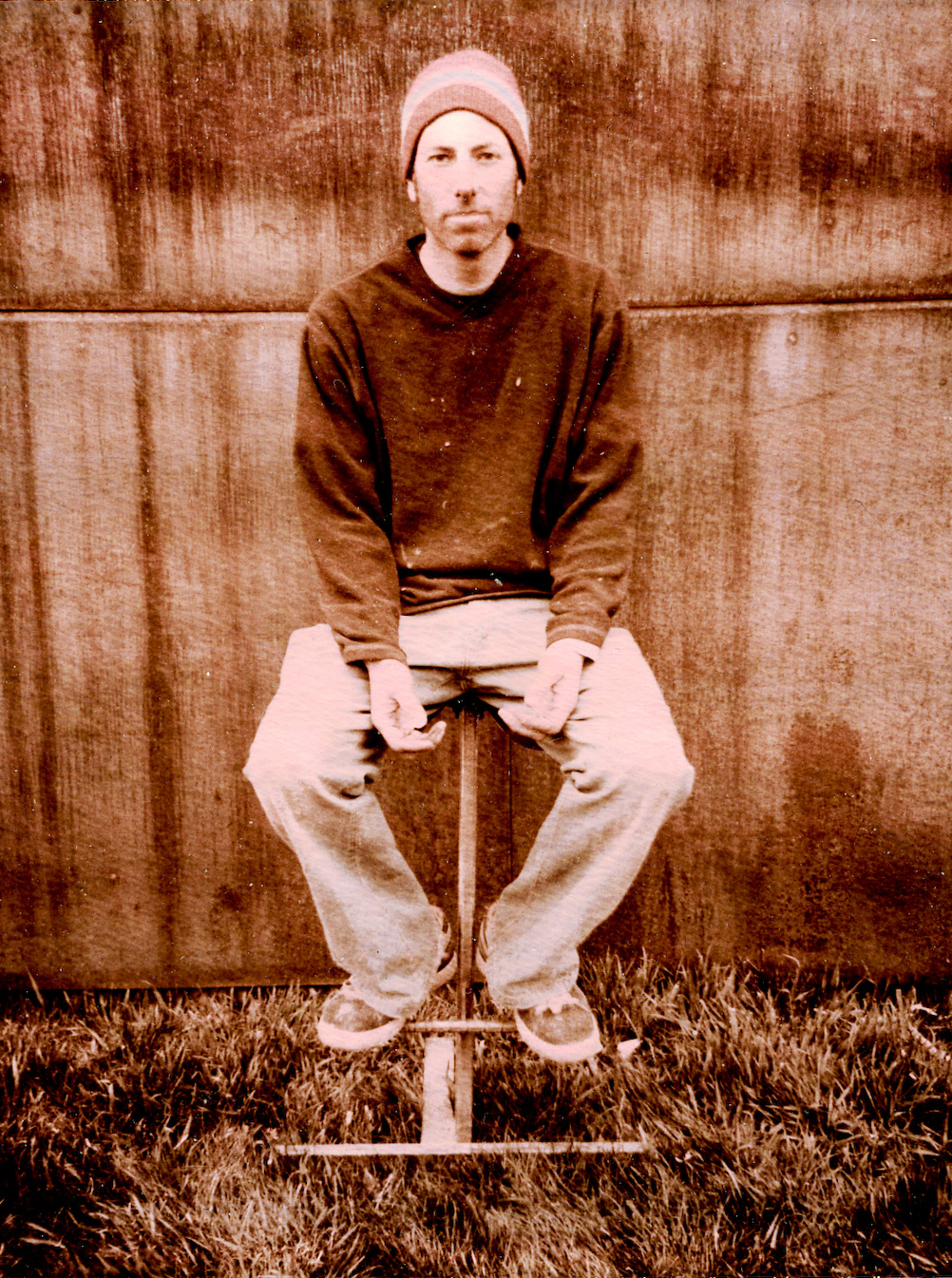

- Top Left and Bottom: “Cabinet of Birds Robot” (detail). • Right: “Robots” | Dood and Clay | Approximately 50 inches high

No Comments