15 Feb Artist of the West: Water, Paint, and Paper

“The gods do not deduct from man’s allotted span the hours spent in fishing.”

— Babylonian Proverb

For watercolorist Jeffrey Craven, the river isn’t just a place to paint, it’s a place of deep reflection.

“Cell phones are not allowed in my drift boat,” he says. “I don’t like the motor boats. In a drift boat the river has you, it takes you where the river wants to take you. You can only divert yourself for a stop along the way. You’re in the flow of nature. People on the river are looking for the same thing that people sitting in a church are looking for; it’s not necessary to catch a fish.”

The success of Craven’s watercolors can be credited with his ability to convey that feeling in his work.

“Maybe it’s making atonement for something or maybe it’s an escape from life’s reality that lures a person to the natural landscape,” Craven says. “When I was looking up a quote from Thoreau one day, the article stated that a person does not go buy a drill because they need a drill. They go buy a drill because they need a hole. There is often something inherent that a person is reaching for. My fishing scenes usually try to capture that ‘one with one’s self’ thing.”

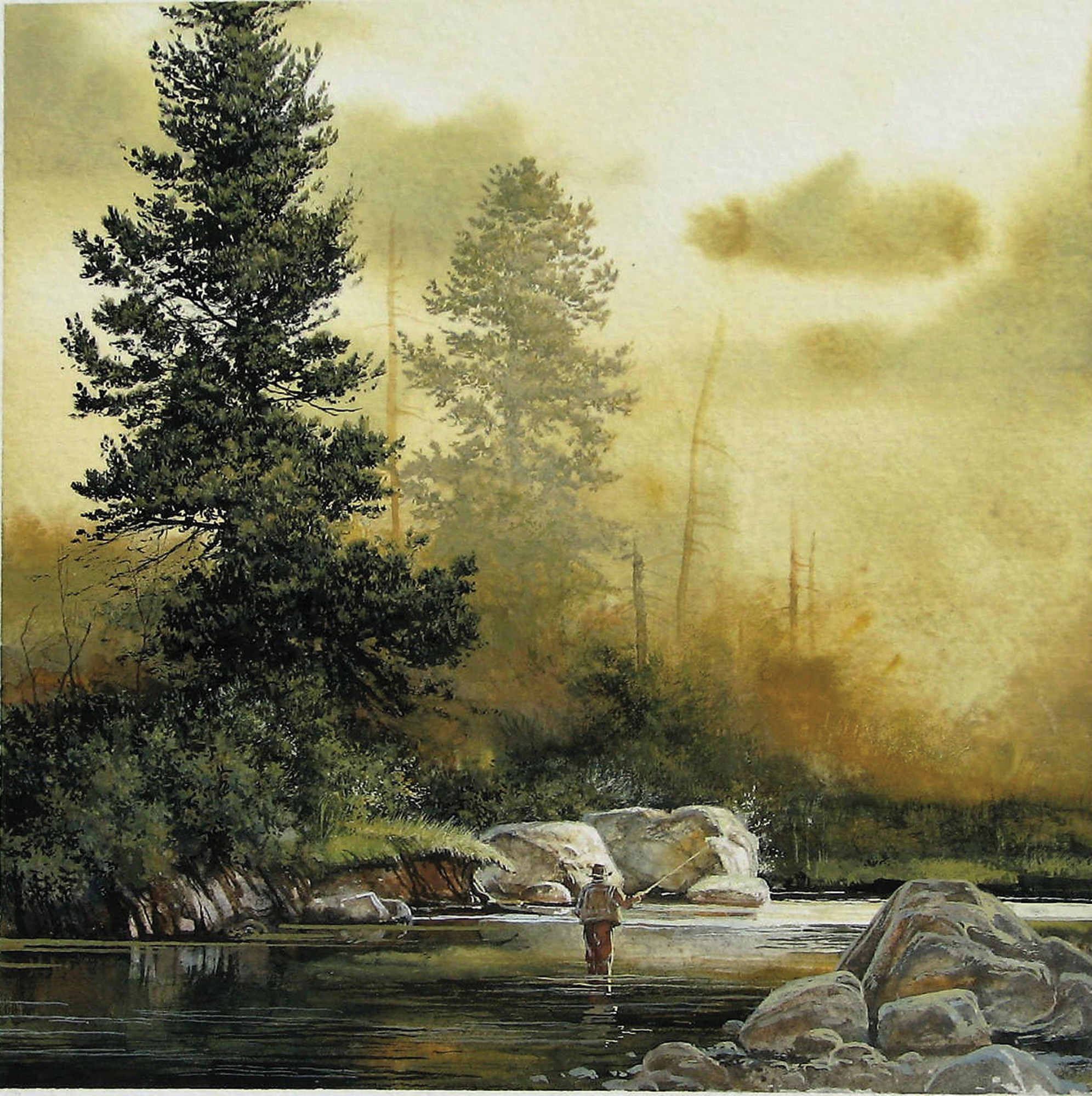

Craven’s use of color and light, combined with an innate knowledge of the river, transports the viewer. He usually paints with a particular place in mind, but not directly transposing everything from the scene into the painting.

“I do go out for field studies, [but] it’s the abstract that inspires the final piece,” he says. “I draw from the colors, the composition. The photograph doesn’t break down values of distance. On location you can see the atmosphere as it goes into the background. The painting becomes more real than a photograph.”

The beauty of watercolors has to do with the way the pigment reacts to the paper. Sometimes it can be subtle, sometimes tender. For Craven, it’s the perfect medium to express the kind of things he wants to say.

“It’s exciting when the water, the paint, and the paper do their own things,” he says. “It’s the most pleasant accident. It can look like light busting through the skies. In watercolor, you can just sit back and let them do their own thing. In oils, each stroke you place is deliberate and controlled. In watercolor, you ache for those accidents, and when they occur the adrenaline happens.”

Curtis Tierney, of Tierney Fine Art, represented Craven for seven years until Tierney sold his gallery. Tierney, now a private dealer selling period American and Western paintings, saw something in Craven’s paintings that he knew would translate to a wide audience, especially those who understood the essence of fly fishing.

“You feel an awakening or a discovery of optimism when you’re in the presence of his paintings,” Tierney says. “Color, atmosphere, and mood [are] what he does so well. He’s really conjuring up a feeling. He can do that because he is so connected to his art.”

Tierney cites Craven as one of the most talented artists painting today. “He is a painter of incredibly high caliber,” he says. “Flat out, without hesitancy, I would categorize his watercolors as among the best of any past or present watercolorist in the nation. Every painting I got from him was consistently top quality. Out of all the current [still living] artists I represented, Jeffrey’s paintings were the most commissioned by all my clients. In seven years, he did 30 or 40 commissions.”

This says a lot for an artist who taught himself how to paint sitting at his grandparents’ kitchen table in Idaho’s Swan Valley, along the South Fork of the Snake River.

“There was no TV, no telephones,” Craven recalls. “My grandparents were custodians in the little rural school, so when school got out for the summer, the art classes would throw out the used supplies. They’d bring home pieces of chalk and colored pencils. With all those supplies, I had to be an artist.”

The response to his early work was that the picture looked like a tree or looked like a horse. “So I grew up being a realist, and watercolors were the easiest thing for my grandparents to get for me.”

Then, every afternoon, his grandparents — who had an old Chevrolet Bel Air — would throw the fly rods in the back of the car. “We fished all the little streams, but when Grandma didn’t go, we’d go to the big river, the Snake River. It flows through lava rock and it was dangerous. On those days my grandpa would lie about where we went.”

These days, the South Fork of the Snake is just across a field from his studio. “There’s a launch half a mile up the road,” he says. “I can have my drift boat in the river in three minutes.”

The types of scenes Craven is attracted to are of a single person in the river, fly rod in hand, riffles barely discernable, and trees lush against a brightening sky.

“What draws me in is the link of one person connecting with the experience of being on the river,” Craven says. “I always have the camera, whether it’s my nephew shooting me or me shooting him. So I have those photographs to work from, but I do some sketching also. I’m kind of a stickler about plein air, I’m not into the Impressionists. Plein air has its place, but I think they sidestepped the whole process in a way — it just feels like an unfinished work.”

Craven has had three one-man shows on Madison Avenue in New York City. He’s always surprised when people in a big city want his paintings on their walls.

“The guy who bought one of my paintings has a penthouse on Fifth Avenue,” Craven says. “He comes home, looks at that painting, takes a deep breath, and relaxes a little bit because he can have the same connection the artist had at that minute. It blows me away how art can transport you.”

Even the younger art collectors find something that touches them in Craven’s work. He thinks that they’re looking for what’s been lost in the expansion of urban development.

“It’s a theme that runs through a lot of stories,” Craven says. “Man searching for his place in the world. We need that connection with nature, the time to reflect and let our minds relax. There’s something lacking in our humanity that drives us outside. What I paint translates to people, whether they’re close to nature or not.”

Alissa Banks, owner of the A. Banks Gallery, currently represents Craven, and she loves selling his work. “He’s highly collected, especially his fly-fishing watercolors,” she says. “People come in every year excited to see his new work, since he’s a fly fisherman as well, and that’s so brilliantly conveyed in his paintings. There’s something magical about them.”

The vividly portrayed details, set within the gentle rendering of a specific area, are the key to Craven’s work.

“His work is incredible,” Banks says. “It feels like his pieces are a treasure. And the collectors see that as well. He’s more illustrative than most watercolorists. He includes a lot more detail, and I think that fans of watercolor painting are drawn to that.”

With each painting he sends to the gallery, he includes a story about the day and his time on the river, the experiences that influenced the piece.

“That’s why other fly fishermen are so attracted to his paintings,” Banks says. “This time of year, I can’t keep his work on the wall.”

- “Browns and Diamonds on the Ruby” | watercolor | 8 x 15 inches

- “Where the Gallatin Slows” | watercolor | 6.5 x 12 inches

- “Where the Gallatin Slows” | watercolor | 6.5 x 12 inches

- “A Perfect Day” | watercolor | 8 x 12 inches

- “Mystic River” | oil on board | 16 x 22 inches

No Comments