29 Sep Artist of the West: True Grit

“Blessed are they who see beautiful things in humble places where other people see nothing,” observed the 19th-century Danish-French painter Jacob Abraham Camille Pissarro. That quote, shared recently with Western artist Beth Loftin by a close friend, impacted her greatly, validating her devotion to depicting real everyday figures of the early-20th-century West, many of them inspired by old photos she finds in antique stores and secondhand shops on her drives in and around Oklahoma and Montana.

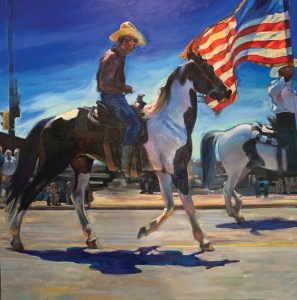

THE PARADE | oil on canvas | 60 x 60 inches

The source of those words is also strikingly apt, considering that Pissarro came to be known as the Father of Impressionism. Loftin herself creates images in a contemporary painterly style with an interpretive freedom and lucent, vivid palette that may well elicit echoes of the freshness found in those pioneering painters of almost a century and a half ago.

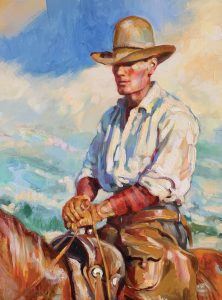

Consider, for example, Lifting Fog, one of her favorite recent works. It portrays a working cowboy on horseback, set against the Rocky Mountains as mist rises up the rugged, tree-covered slopes. Apart from its undeniable sense of the authentic West, this is no romanticized vision. The man looks rawboned and ruddy; his hands are gnarled, and his well-worn high-crowned hat is pulled low to shield his eyes from the morning sun.

LIFTING FOG | oil on canvas | 16 x 12 inches

“I never did like the romanticized West,” Loftin says. “I liked the true cowboy, the really grungy ones like I found in old 1920s photos.” Yet, the brightness of the oil paints Loftin chooses and mixes — and the translucency with which she applies them — endows the finished composition with a purity and nobility that cuts to the very heart of the Old West’s character.

“There’s true-grit appeal, an authenticity to the characters that Beth paints,” says Curtis Tierney, who proudly shows her work at Tierney Fine Art in Bozeman, Montana. “And she does that in an incredibly attractive artistic manner, painting with a freedom from constraint that most artists don’t have. She loves to push color around, with brushwork as beautiful as the subject of the painting itself.”

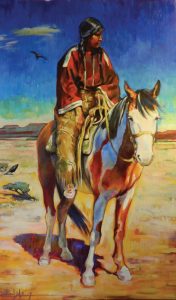

RAVENS | oil on canvas | 60 x 36 inches

Both her connection to people of humble roots and her free spirit come naturally. Loftin grew up in southern Oklahoma’s oil and horse country, and she was obsessed with horses from an early age.

“I just could not get enough of them,” she says. “I was horse crazy and would watch anything on TV and read any book on them, studying the illustrations. Once, somebody tied up a horse in the alley behind our home, and I was smitten beyond belief.”

As a 4-year-old, she ran off to the local mall to gaze at collectible Breyer horse models sold at Woolworths. During second grade, her parents grounded Loftin for riding her bike several miles into the surrounding countryside to visit horses in people’s pastures. “I would do chores for money to save up for a pony, and if someone’s horse got loose, I would take it home and hide it in our yard until my parents found it and made me return it.” By third grade, she regularly snuck away to nearby farms to knock on doors and ask permission to ride the horses — “and I’d ride them even without permission,” she says with a laugh. Often, she was invited in to share a cup of tea or glass of lemonade with people old enough to be her grandparents or great-grandparents, listening avidly to their stories of bygone days.

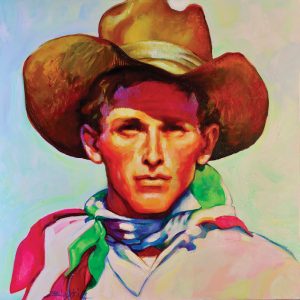

JIMMY | oil on canvas | 30 x 30 inches

While Loftin’s parents were frustrated by her escapades, they were delighted by her artistic talent, which first manifested when Loftin was 3 or 4, when she drew a rendition of Cinderella’s pumpkin coach — pulled by a team of horses, of course — on the tiny cardboard base of a Hostess Sno Ball snack cake. She was drawing almost as often as she was trying to run off and ride.

Her favorite subjects eventually came closer to hand. “My parents found a farm to ranch when I was around 9,” she says, adding that at 10 years old she and her sister were each given a horse. It was Christmas and Loftin’s was a paint. “I named him Randy, and he was the love of my life.”

By the time she was in high school, Loftin had found a way to combine her passions, painting very tight, photorealistic portraits of horses and riders for top local breeders and trainers. One rewarded Loftin for her work with a registered 6-month-old paint filly she named Cowboy’s QT, “who’s been the iconic horse in my life, my mountain-riding horse in Montana” — and the steed she proudly poses on in a black-and-white photograph on her website.

SMUG | acrylic | 40 x 40 inches

Loftin’s prodigious artistic talent landed her a full scholarship to the University of Science and Arts of Oklahoma in Chickasha. “I picked this college because students studied the Masters there while other universities were doing avant-garde, Modernist art — just letting kids paint what they felt,” she says. “I desperately wanted classical training, color theory, design theory. I had a natural eye, but not the technical knowledge.”

Having grounded herself in that knowledge base, Loftin felt ready to cut loose after graduation. Settling into a house beside the Cimarron River in Coyle, Oklahoma, “I had time to myself to meditate, concentrate, pray — to figure out what I needed to do to be happy with the process of art,” she says.

She decided to combine her love of Western history with her love of old photos, breathing life into historic images through painting. “Using black-and-white photos as my source material allows my mind to invent the color with my own feelings,” she says. The results led to her first major exhibition, a collection of works displayed by the Oklahoma City Museum of Art that were inspired by vintage photographs from the 101 Wild West Show Ranch. The exhibition, in turn, led to a feature article in Persimmon Hill magazine, which was, at the time, a publication of the National Cowboy Hall of Fame (now the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum). By her mid-20s, Loftin was well on her way toward a career as an artist worthy of serious collectors’ attention.

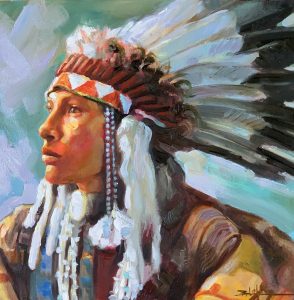

HOPE | oil on board | 12 x 12 inches

While helping to manage and teach in a public art facility in Stillwater at the age of 30, she met and married a biology research professor, and in January 1993 she moved with him to Bozeman. Once there, she felt as if she’d died and gone to heaven. “The way snowflakes look when the morning sun hits them was so incredibly beautiful that I was speechless.”

Her first representation in the Rocky Mountain West — in Jackson, Wyoming — came quickly, when a buyer of hers stopped at a gallery there “and told them they needed to call me and get my work.” Which they did. Loftin’s reputation steadily grew, leading to her selection as the official poster artist for the 1999 Jackson Hole Fall Arts Festival. Several other galleries in Jackson have since represented her, and her work is currently available at West Lives On Gallery.

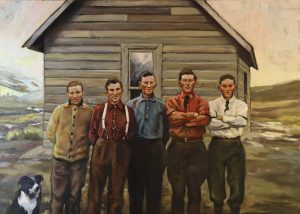

BACHELOR S ON THE RESERVATION | oil on canvas | 26 x 40 inches

Meanwhile, her first marriage had come to an end, and she eventually met and married an assistant district attorney from Los Angeles who had a second home on a ranch in Big Timber. They had a son together. Then, after Loftin’s mom began ailing in 2011, she and her son moved back to Oklahoma. “There, my son had aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandparents, and a beautiful farm to garden with his grandpa,” she says. “I will never ever regret coming back to be with my mom.”

Having so much family support also gave Loftin more time to paint, with exceptional results. She continues to paint her photo-inspired works, such as Jimmy, a close-up portrait of a young cowboy around 1918, painted in a high-key color palette; and Bachelors On the Reservation, painted in more muted tones, showing a lineup of five awkward-looking young men (and one border collie) dressed up for their formal photo in front of a cabin they share on the Indigenous land where they work, with a title taken from the pencil inscription Loftin found on the back of the image. She also snaps images to paint from old Westerns she watches on video, such as Smug, a portrait of self-confident Western actor Clint Walker, best known as the star of the late 1950s and early ’60s TV series Cheyenne. She creates stunningly sensitive Indigenous portraits, such as a young warbonnet-wearing warrior in Hope, or a young Native woman on horseback in Ravens. And she occasionally delves into the creative possibilities found in sculpting and casting works in bronze, including the energetically rendered Miles City Bronc, which captures a cowboy mid-buck. “I’m going to set up a dedicated space to do my bronzes,” she says. “Working with both hands in clay just gets me out of my head.”

MILES CITY BRONC | bronze | 24 inches tall

That three-dimensional medium adds yet another avenue through which Loftin can share the down-to-earth Western stories she feels compelled to depict. “I’m not a city person,” she says. “I’m just a country kid who puts her feet in the dirt and forages wild foods. And the day that my parents got a farm was the happiest day of my life.”

From his base in Los Angeles, Norman Kolpas writes about art, architecture, design, travel, dining, and other lifestyle topics for magazines including Western Art & Architecture, Southwest Art, and Art Times Journal. He’s a graduate of Yale University and the author of more than 40 books, the latest of which being Foie Gras: A Global History. Kolpas also teaches nonfiction writing in The Writers’ Program at UCLA Extension, which named him Outstanding Instructor in Creative Writing.

No Comments