03 Jun Artist of the West: The Mysterious Lightness of Being

Jennifer Li first became intrigued by The Art Students League of New York because of carriage horses. It was the early 1980s, and she was living in New York City after studying at Bennington College for two years before transferring to Sarah Lawrence, where she received her undergraduate degree. Though she had been drawing for most of her life, the art classes at both schools — which focused mostly on Abstract Expressionism and color field painting — didn’t speak to her. She had a love for more figurative work, so she studied literature and philosophy instead. But once she was in the city, she became acquainted with several friends of friends who worked as carriage drivers in Central Park at night and studied at The Art Students League by day.

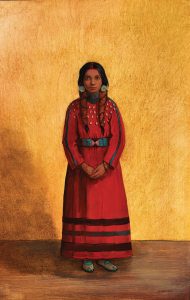

Elk Tusk Dress | Oil | 12 x 18 Inches

“There were carriage horses that lived up on the second floor of some buildings on the west side,” Li recalls. “And these students would bring them downstairs, put them onto carriages, and give rides to people in the park. There was a big culture of people like that who lived in my building — several of them — and they all studied with this guy named Frank Mason at The Art Students League.”

The league, founded in 1875, was known for welcoming both amateur and professional artists to study in an informal setting. And that was exactly what Li wanted. For the next 11 years, she studied with Mason and Harvey Dinnerstein, both renowned figurative painters who were influenced by 17th-century Dutch painters, such as Peter Paul Rubens, and the Flemish Baroque artist Anthony van Dyck. This was a style that also spoke to Li: representational Baroque images made with large, painterly brushstrokes.

Falconer | Oil | 9 x12 Inches

Li was also fascinated with the “Little Masters” and other artists who worked on a small scale, creating finely detailed paintings of everyday life. “Our teacher would take us to The Metropolitan Museum [of Art] as a class when we weren’t doing our studio painting in the classroom,” she says. “I was always really entranced with the little genre paintings showing normal people doing interesting things. There was always something mysterious going on in them.”

Although Li grew up in Mill Valley, California, she and her family spent summers at a ranch near Augusta, Montana. And after living in New York City for nearly 20 years, she settled in northwestern part of the state in 1998.

Looking at Li’s work now, you can understand her attraction to the colorful vision of carriage horses in New York City being escorted from a building. Her portraits are a striking combination of Baroque style and detailed genre paintings that are full of mystery. Over the years, Li has become well-known in galleries across the region for her rich figurative paintings, with representation at Dana Gallery in Missoula, Stapleton Gallery in Billings, and Beartooth Gallery in Red Lodge.

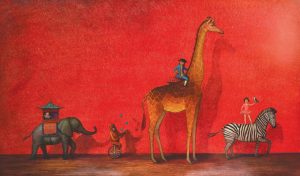

Circus Parade | Oil | 24 x 36 Inches

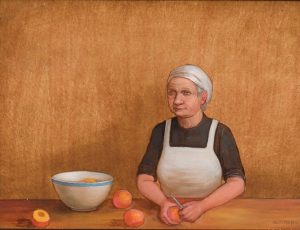

In a piece titled “The Peaches,” an older woman donning an apron is slicing peaches to put in a bowl. It’s a straightforward, austere image made with rich golden oranges and browns, punctuated by a few white and black details, and glowing with light. Li’s knack for luminosity is one way the paintings pull you in, and once you’re in, the details keep you there. For instance, in this one, the woman’s face is serious but kind. And though it’s hard to know what she’s thinking, there is clearly a depth of life to her. That’s the power of Li’s characters.

“Besides her ability to do this beautiful, luscious layering with her oils and her rendering of the physical being, there is also a personality and a spirit in all her characters,” says Liz Wetherby, director of the Dana Gallery. Dudley Dana, the gallery owner, recalls a patron admiring one of Li’s domestic-themed paintings of a woman cooking with a cast-iron pot. The patron said it was beautiful but made him feel uneasy — perhaps she had a man’s head in there, he joked.

The Peaches | Oil | 9 x 12 Inches

Other paintings focus on the fantastical, like riffs on children’s fables and imagery of old-fashioned circuses featuring children and animals together. It’s both the everyday domestic images and the little girls taming lions that have compelled many of her fans to see her work as feminist — and Li doesn’t disagree. “I’ve done numerous paintings of something like a young female lion tamer who is facing a very big, fierce-looking animal,” she says. “I think that I may be talking about female empowerment without articulating it in language.”

Her circus themes are also fueled by her interest in the origins of these types of events. She once read about Cretian frescoes depicting ancient Minoan acrobats who would leap over the backs of charging bulls. “The bull leaping was, in a way, a precursor to the Roman circus,” she says. “And it relates to how cultures often expressed their fear of animals that might kill them.”

Brother Wolf | Oil | 12 x 16 Inches

Recently, Li — who also teaches at Flathead Valley Community College in Kalispell — went back to school at the University of Montana for a master’s degree in integrated art and education. And, surprisingly, she has shifted to ceramics. Because color glazes don’t give her the rich effect she loves in her paintings, she is only working in bone-white clay and clear glaze.

All of this is a departure for her, though her wild animal-centric themes are still present in her new works, such as the 36-inch-long crocodile sculpture that she’s currently making. And in a way, the gleaming white porcelain provides a similar tension between light and a subject whose nature is ultimately unknowable.

Dog | Porcelain

“It’s fun to express these animals in a three-dimensional form,” Li says. “I love working with porcelain. It’s extremely finicky and smooth, and you can get a really beautiful finish on it.”

Erika Fredrickson was the longtime arts editor for the former Missoula Independent. She’s currently a contributor to the Montana Free Press, the editor of a zine called The Garden City Beast, and a co-producer for “Death in the West,” a podcast dedicated to strange crimes and historically resonant intrigues of the American West.

No Comments