01 Jun Artist of the West: Returning to Analog

For Bozeman, Montana-based mixed-media artist Miles Glynn, inspiration is instantaneous. It’s a melding of color, shape, sound, and feeling. “There are moments where everything comes together visually,” says Glynn. “The lighting, the senses, maybe the music I’m listening to, it creates a moment or a feeling that I then want to capture and integrate into my work.”

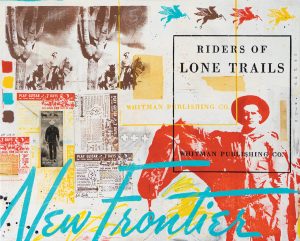

The self-taught creative merges old and new, weaving threads of history into contemporary works of art that resonate with viewers and render a physical feeling. In a style akin to the likes of Andy Warhol, Glynn uses serigraphy to produce large-format prints, juxtaposing familiar personalities and Western motifs with new colors and neon, or artful design elements from old advertisements, wallpapers, and magazines.

Westernish no. 8 | mixed media | 50 x 62 inches

The son of a U.S. Army photojournalist, Glynn was raised with a photographer’s eye. He’s versed in the physical process of making a picture and developing film, so it’s no surprise that contrasting imagery is often what he finds most compelling. For each of his pieces, a set of images undergoes a transformative process, moving from analog to digital and back to analog.

“An advertisement from an old magazine would have been printed using some sort of analog printing press,” he says. “I then scan it and bring it into the digital work environment, where I prepare it to be turned into a large silkscreen stencil. It returns to analog form when I use my hands to push the ink through a silkscreen and onto the canvas.”

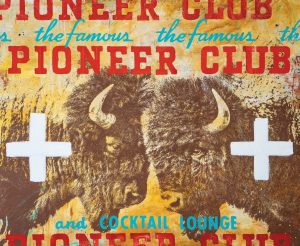

Westernish no. 13 | mixed media | 78 x 96 inches

The process of serigraphy underscores the weight of Glynn’s pieces. He lugs around 4-by-6-foot screens, often working on the concrete floor of his studio. There’s a curing and drying time, layering, and in the end, Glynn cleans up with a pressure washer. “It’s a very physical process. My knees and my back can attest to that,” he says, adding that people are welcome to contact him about visiting his Bozeman studio and witnessing the process.

Recently, Glynn was struck by the neutral color tones he encountered in a hall lined with ancient Egyptian papyrus scrolls at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. “I was fascinated by them,” he says. “They were very neutral and yet, at the same time, they had this presence to them.” Glynn fully embraced the experience, and two months later he was already on his fifth piece in a series inspired by the papyrus; at 78-by-96 inches, it is his largest single work to date. “I like the presence and weight that these can have when they’re larger,” Glynn remarks.

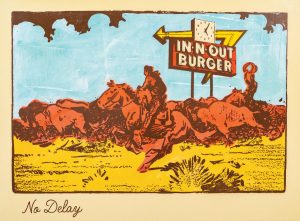

Westernish no. 1 | mixed media | 50 x 62 inches

This new series is predominated by neutral colors. Keeping with his characteristic Western style, Glynn juxtaposes an image of two bison he photographed about a dozen years ago at South Dakota’s Wind Cave National Park, with wording from a mid-century matchbook that proclaims the name of a since-closed Las Vegas casino, the Pioneer Club. Evocative and inquisitive, it employs familiar qualities to engage viewers and allow them to think about Western art in a new way.

As a child, Glynn viewed the landscapes of the Western U.S. from a car window, traveling with his family as they moved around the country. “I developed a love of traveling and an affinity for the West at a young age, and it’s stuck with me all along,” he says. “One of the challenges that I enjoy is taking these images and narratives from our past and trying to keep them in the conversation and give them a place and context within a contemporary piece of artwork.”

Annie no. 1 | diptych | mixed media | 62 x 100 inches

While the main premise remains the same, Glynn’s style is ever-changing. He combines photographs of horses, cattle, and wildlife with vintage wallpaper from historic buildings in his Wallflower series, while his pulp WESTERN works integrate pages from Western pulp fiction magazines, neon lettering, and jolts of color.

“The thing about Miles that’s so incredible is that he’s constantly evolving, more than any other artist I’ve ever represented,” says Courtney Collins, of Courtney Collins Fine Art in Big Sky, Montana. “He’s always moving and changing. His work pushes the limits of Western art.”

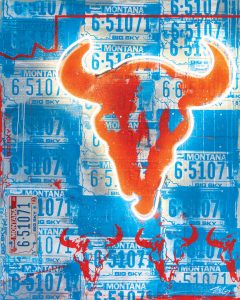

Montana no. 1 | mixed media with neon | 60 x 48 inches

Collins’ gallery was the first to represent Glynn, and she says it’s been an honor and a privilege to work with him over the past four years. “His work is storytelling. It’s a narrative that always involves history.” For many of his pieces, Glynn includes background information so viewers can contemplate the historical context. He might include the cover of a predominant magazine or provide a written description that details the origins of his relics. In this way, Collins explains, Glynn’s art transcends the here and now. “It’s not just a painting,” she says. “It’s a piece of history.”

Lovers & Fighters no. 9 | mixed media | 72 x 132 inches

Jessianne Castle is a freelance writer and editor who grew up under Montana’s big sky. She lives in Kalispell where she writes about life in the West.

No Comments