02 Feb Artist of the West: Repainting the Rural West

Being out on the range in the rural West forces a change in how you relate to the world; your safety depends on it. But even when you’re by yourself, hours from the closest town, you’re anything but alone — the landscape keeps you company. “The landscape demands your presence and your awareness, which we so easily give up in cities and urban areas,” says western Montana-based artist Melissa DiNino. Paying close attention amplifies your senses and opens your eyes to the beauty and complexity that imbues even the most ordinary of moments. “My first time riding out on the plains was very jarring, but at the same time, I was crying — it was the first time I felt true happiness, just the pure joy and peace of being alive.” DiNino’s watercolors capture that rural tilt in perspective, revealing new layers of heady emotional depth that, in turn, shift the viewer’s understanding.

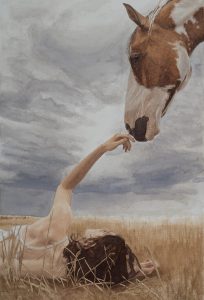

Liberation | Watercolor | 22 X 15 Inches

DiNino did not set out to become an artist. Growing up, animals were her primary interest; she studied biology and conflict resolution in college, tailoring the latter degree to animal–human relations instead of international politics. Her program connected her to work at a wolf conservation center, where she learned about the complicated relationship between ranchers and predators. “It frustrated me how much we dehumanize people, and anthropomorphize wolves,” says DiNino. “It felt like they were always in a state of war.” After graduating, she found her eye caught by a range rider position in Montana’s Centennial Valley; working on a ranch wasn’t her original plan, but the position was too enticing to pass up. Within weeks of applying, she found herself on an airplane headed west.

Range riding is a re-emerging profession, an evolved version of the traditional livestock rider. DiNino spent her days on horseback, monitoring cattle for signs of illness and injury, tracking predators, and gathering information about wolves and grizzlies in the area. The goal was to work with the greater ecosystem, not against it, to keep the herd out of harm’s way. Being a range rider brought DiNino into a tight-knit ranching community, teaching her how its bonds — with both humans and non-humans — are key to surviving in the wild landscape.

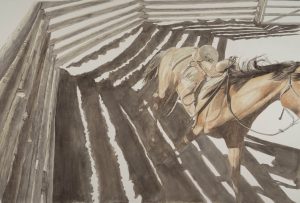

Shadow | Watercolor | 16 X 12 Inches

A few years into her role, art arose as a necessary emotional outlet. An incident between a grizzly bear and one of DiNino’s fellow range riders rocked the community, leaving her unsure of her path forward. Experimenting with watercolors became a way to work through the turmoil. “I played with art growing up, just as a hobby — it was an easy thing for me to fall back on and use as a way to express myself in difficult times,” says DiNino. But with limited experience using the medium, DiNino had to be her own teacher, learning the temperament of the paint through trial and error.

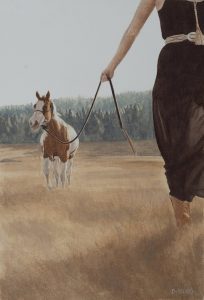

Presence | Watercolor | 10 X 14 Inches

Despite her lack of formal experience, DiNino’s technique is masterful — reminiscent of works by storied American artist Andrew Wyeth, while remaining wholly unique. As is often said of Wyeth’s works, DiNino’s paintings catch you off guard, drawing you in with their magnetism. “As far as a watercolor artist, I’ve never really seen anyone use the medium the way that she does,” says Lindsey McCann Jastram, who represents DiNino at Old Main Gallery in Bozeman, Montana. “She’s not afraid to use negative space in her compositions, then really hones in on the specific details, and does them so perfectly.”

Ghostrider | Watercolor | 30 X 42 Inches

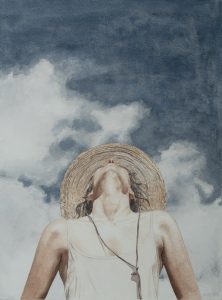

DiNino captures an instant in time with minute, intentional strokes that invite the viewer to return to the scene again and again, unveiling new meaning each time. She sets her subjects against sweeping backgrounds, conjuring the gaping horizon and endless plains famous to Big Sky Country, while the negative space makes the canvas pulse, setting the tenor for each work. A subdued palette infuses her canvases with a feeling of windswept wear, conveying the very real lives and histories that exist beyond the boundaries of the frame: That woolen hat has endured many winters, those boots have been in countless stirrups.

Reverie | Watercolor |30 X 22 Inches

DiNino’s surroundings are her subjects: a flock of sandhill cranes taking flight in autumn, a young rancher looking out over the plains, a bird dog posing in front of his prize. But most often, DiNino captures vulnerable moments of understanding, frustration, and love between humans and horses. Old Main Gallery hosted DiNino’s first solo exhibition, entitled With Silence Comes the Sight, in October 2021. The collection explores a journey to connection and healing between DiNino and her horse, Willa, whom she rescued from a Texas slaughterhouse. The paintings chronicle “moments of light” between the two, when the bond felt trusting, “along with the times where there was a resistance,” forcing DiNino to question what she was doing wrong and “confront things within myself that may have been causing the problem,” explains the artist.

Incongruence | Watercolor | 14 X 10 Inches

Perspective plays an important role in the series, instilling each work with unspoken volume. In Shadow, DiNino has the viewer looking up, as though observing the scene from the vantage point of a blade of grass. The black folds of the subject’s dress lead to a point, bringing our focus to the knuckles of her clenched fist, before moving our gaze to the overcast sky above. The choice makes the quiet scene feel loud and off-kilter, the subject’s solitude clearly wrong. Being alone doesn’t make her strong, it sets her adrift — a message that varies sharply from canonical American Western art, which often elevates fierce individualism.

Bloom | Watercolor | 16 X 12 Inches

The theme of unity appears throughout DiNino’s work, reflecting her own experience. “Historically, Western art has been very man-versus-man, man-versus-nature,” explains DiNino, “but in the West that I’ve come to know, I’ve seen how you have to fall in sync with nature and work with nature to survive. And there’s just so much that you can learn about a landscape, yourself, and your community if you’re willing to take a closer look and listen, and not fight against it.”

Halina Loft is a writer and editor based in Bozeman, Montana. Before coming west, Loft worked as an arts editor for Sotheby’s, an auction house headquartered in New York City. When she’s not writing, Loft can be found running up the college M trail, or skiing down Bridger Bowl.

No Comments