01 Dec Artist of the West: Pure Plein Air

Aaron Schuerr sets up his easel on a tranquil Sunday afternoon, framing his view of the place where lofted clouds graze the mountains. The sun, fat with heat, rolls and slides across the field. Schuerr holds a small sketchpad and, lifting his head to the sky, puts pen to paper.

“It’s a way for me to simplify everything down to basic shapes and a few different values,” he says. Within the rectangle of paper appear flat-bottomed clouds and hints of distant fields. “I used to be terrible about sketching because I thought of it as wasting time. I wanted to get to the good stuff. But painting is about seeing abstract forms and finding a way of making that interesting; not just beautiful, but compelling enough for me to take the time to paint.”

For Schuerr, painting is his means of understanding, of filtering and incorporating polished and thorny worlds.

Once he’s set on a perspective, his mind anchored in the values and lines and something of a composition, he readies his palette: eight compartments each filled with like-toned pastels.

Pastel painting makes up about 80 percent of his work, the rest of the time he uses oils. Today he needs pastels. He starts with geometrical shapes assembled in a jigsaw of greens and pink-blues. He knows he wants the piece to be about the progression of clouds as much as it will be about the trees and fields. His hand hovers over the colors, waiting for the magnetic leap of faith that starts every piece.

“When I’m looking at a location I’m looking for the negative space,” he says. “Like here, when I look all the way back there I see the cottonwood trees, I see the dark mountains and a luminescence. It’s a way for me to forget that I’m seeing trees and mountains, but to concentrate on the shapes between them. It’s about the relationship of forms, whether abstract or representational. They have to be interesting and varied. The point of being able to see that relationship makes it poetic.”

Wind cartwheels through the dried weeds, a frolic of sound amid the solitude of the season. Not strong enough to wobble the easel, or to bother Schuerr, who paints en plein air most of the time. When using pastels, Schuerr doesn’t blend his colors but instead places small strokes next to each other to create tension and keep the intensity of pure pigments.

“I like to see how far I can push the colors and still have the viewer believe me,” he says, reaching for a deep brown pastel pebble. “For me, the value is more important, it gives me a baseline right from the start. From there, I start to adjust and tweak.”

In the distance, two horses nudge at the ground, their tails slow to snap. Cattle are dark against the field, their earthbound tones marked on the canvas. Then Schuerr concentrates on the blue-gray-lavender of the sun-soaked sky. His strokes, almost smudges, form tendrils of swirling light that curl and catch on a moment.

“I want to be really open to feeling excitement about every painting,” Schuerr says. “There should be uncertainty every time I approach the work. If I just painted in a studio I’d develop habits.”

But the happenstance of being outdoors, available to the swift changes in nature, snaring the light at a time when everyone else is looking away, that is the payoff for freezing in the snow, for the trickle of sweat down his neck in the summer.

“When I teach, I say that painting is a translation, not transliteration,” he says. He teaches half a dozen workshops on painting outside during any given year. “If I tried to paint exactly what’s there — it’s impossible. It wouldn’t work. My white and my black are so limited compared to light on a cloud or a shadow. So I’m trying to get the idea of a cloud, not the actual cloud. I want to tell you about my experience of being in this place, at this moment.”

Those moments are present in the finished work, according to Scott Jones, general manager of the Legacy Galleries, who has been representing Schuerr’s work for more than seven years.

“He’s always been one of my favorite pastelists,” Jones says. “I like the fact that he enjoys plein air painting and is willing to hike, camp (and) sweat to get the right reference material for a great painting.”

Sometimes pastel paintings can be harder to sell, but it’s because people don’t understand them. Pastels are pure pigment and withstand the test of time better than oil paint.

“To me pastels are fresh, they’re crisp, and you can get some atmosphere,” Jones says. “Aaron does skies incredibly well. He really gets depth. He captures that atmosphere.”

Although most of Schuerr’s work is begun en plein air, he takes them back to his studio where he can finish his thoughts.

“When it comes to landscapes, he’s incorporating the plein air pieces, which informs what he does in the studio,” Jones says. “And we’re getting some really impressive paintings that collectors are responding to. I’ve noticed in the last year people are attracted to his larger pieces, and that excites me.”

For Schuerr, the move to his studio is about going to a deeper level with an idea. “It’s about processing experiences I had in the field,” he says, “to get a more complete thought.”

His attention moves to the lower third of the painting, where he’s going to think about the abstract nature of the spaces between the trees, with the periwinkle gray of the distant mountains peeking through.

Oddly enough, Schuerr began his painting career working in Abstract art and moved to landscapes from there. As time has gone by and he’s learned more about his own process, the end result may be landscapes but he gets there through the eyes of an abstractionist.

Plein air painter Matt Smith is familiar with Schuerr’s work and respects his ability to cross over between oils and pastels.

“He’s able to paint in both mediums because his work is grounded in the fundamentals,” Smith says. “It makes for work with a stronger presence and it can be appreciated on a larger scale. His transition from pastels to oils is relatively seamless. He has his own calligraphy about what he does. And when you paint outdoors as often as he does, you don’t have time to second-guess yourself. That tends to bring the individual artist out.”

Smith sees Schuerr’s intimate connection to place as the thing that sets him apart from many other landscape artists.

“That to me is very important,” Smith says. “What a lot of artists tend to do is travel around and paint areas other people have painted and in so doing they overlook their own world. Aaron is not doing that. You can feel the personal connection. It’s more than a convenient subject for him. I’ve driven all over the country and it’s beautiful. And of course, he’s just north of Yellowstone, but he doesn’t paint the things everybody does. He tends to find that small, undiscovered corner of a stream.”

It is this intimacy that Schuerr brings to the work: a personal invitation to see what he’s seen, to share in the moments as he’s experienced them. After he shushes a small block of pastel against the rough paper, Schuerr weighs whether it’s done. A delicate fence line appears, disappears, then comes back again. This time it feels right.

“Now, what does it need?” he asks out loud. “It’s easy to overwork things, but I’m getting to the place where I’ve learned to trust the experience and trust my response to stop where I need to stop.”

The piece on the easel feels like the late afternoon in the company of not too distant waters. It whispers of nearness, of movement and weight. The sky is a tumble of color. The mountains hint at abundance and the ripe awareness of promise.

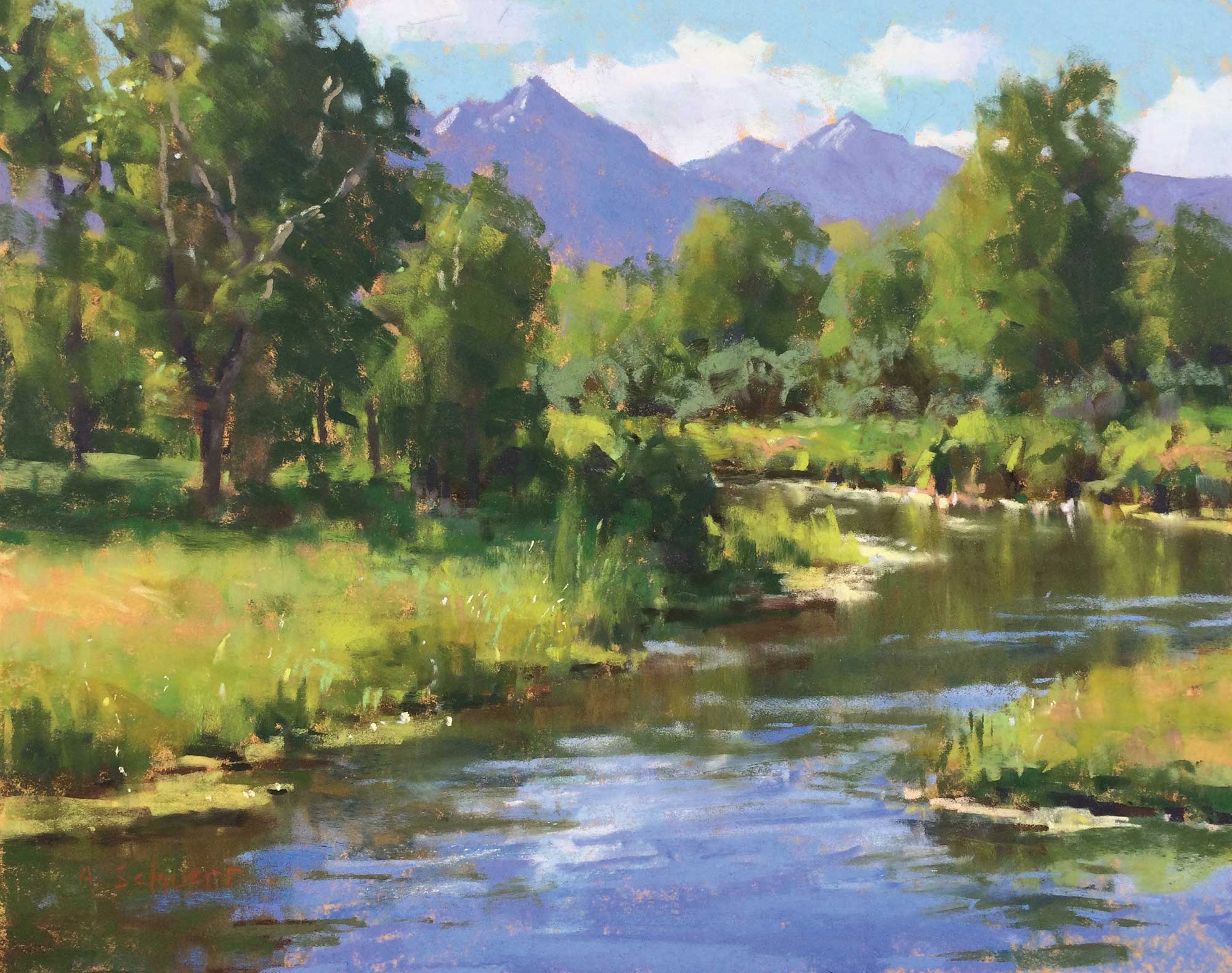

- “The Gallatin River in January” | pastel | 12” x 16”

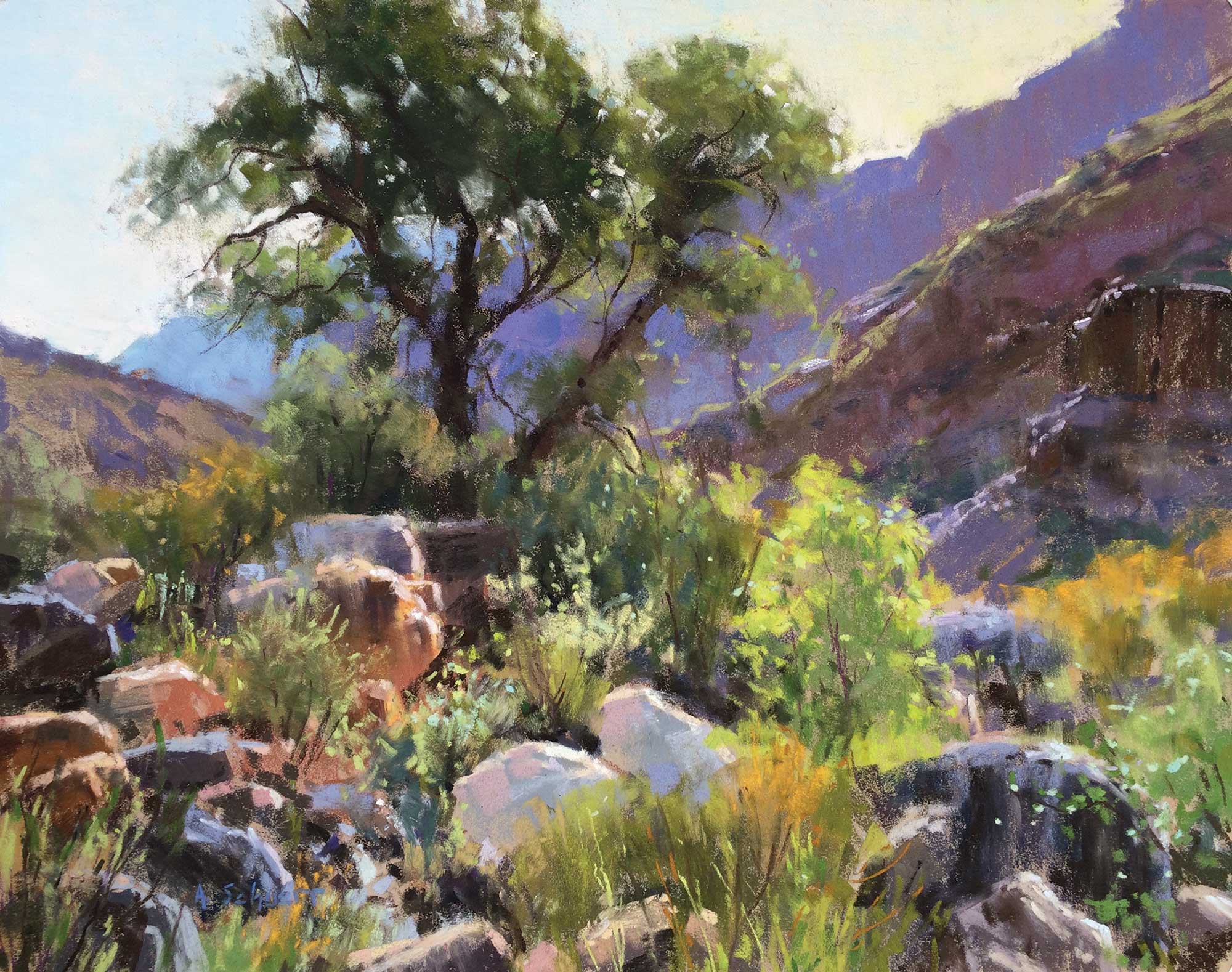

- “Bright Angel Boulders” | pastel | 11” x 14”

- “September Sunset” | pastel | 11” x 14”

- “Cape Royal Color” | pastel | 18” x 36”

- Schuerr often backpacks to remote locales to capture beautiful settings such as this one at Pine Creek Lake.

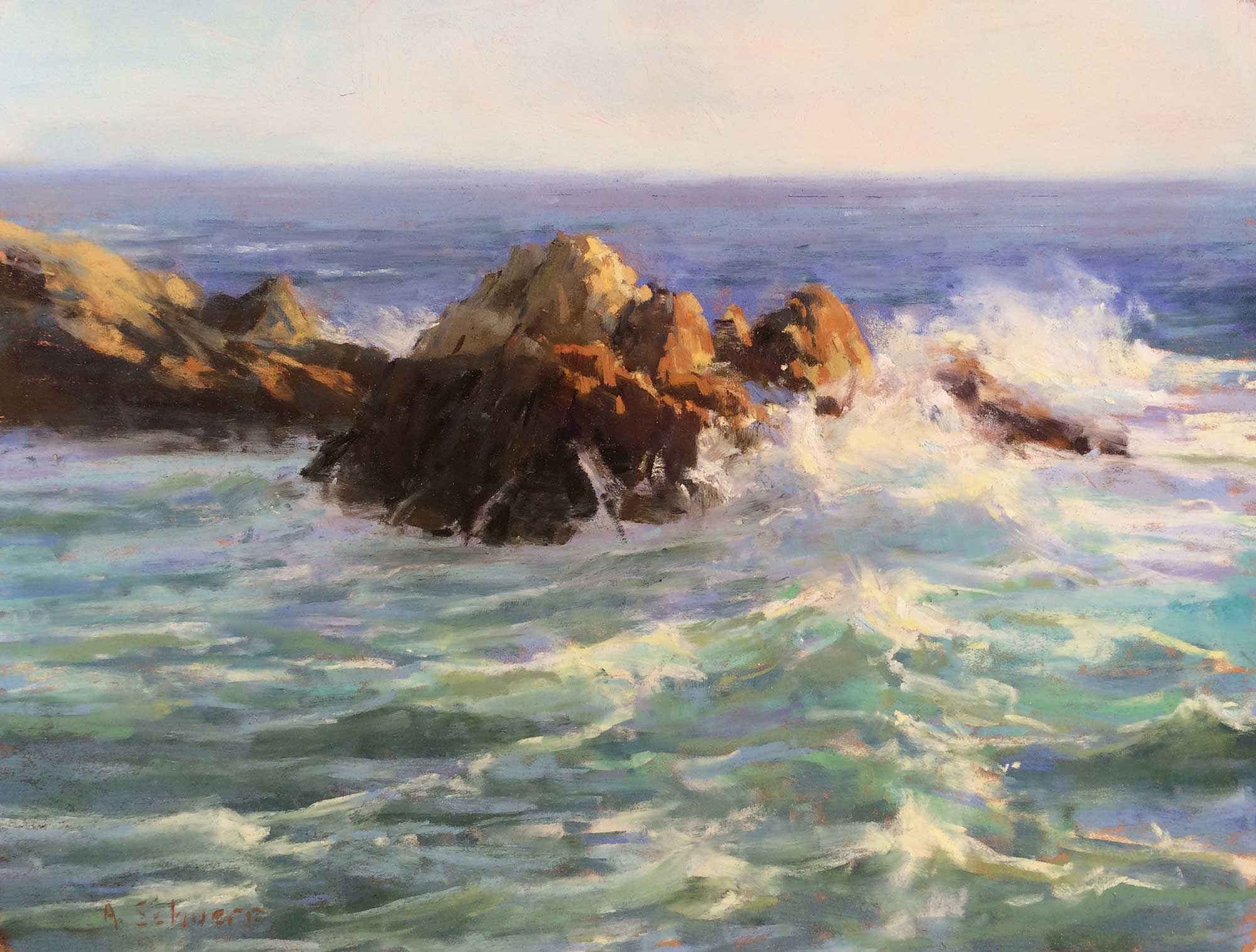

- “Turquoise Waters” | pastel | 9.5” x 12”

- “Verdant June” | Pastel | 20” x 24”

No Comments