25 Sep Artist of the West: Painting History

Imagine a history professor who, instead of writing monographs, got some canvas, took up a paintbrush, and tried to tell the story of the West through a series of vignettes in oils. That might be the best way to describe Don Oelze: he paints history.

“I’ve always read a lot, especially history,” Oelze says, “and particularly the history of the American West. When I paint, I am fastidious about the details because I know the piece will be a failure if an actual historian out there notices a detail that is wrong — a Crow headdress, say, on a Blackfeet warrior. I’m trying to tell a story in my paintings, and every detail has to be exactly right.”

Toward that end, Oelze’s studio outside of Clancy, Montana is much like a Western plains museum. Against one wall is a series of wardrobes and clothing racks with buckskin outfits, beaded dresses, and 1870s U.S. Army regalia; another wall boasts a hat rack with enough cowboy hats of different styles to produce an episode of Yellowstone.

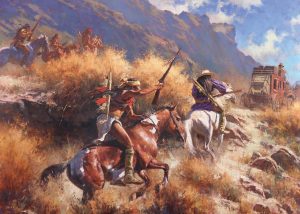

Ambush Road | OIL ON CANVAS | 36 X 50 INCHES

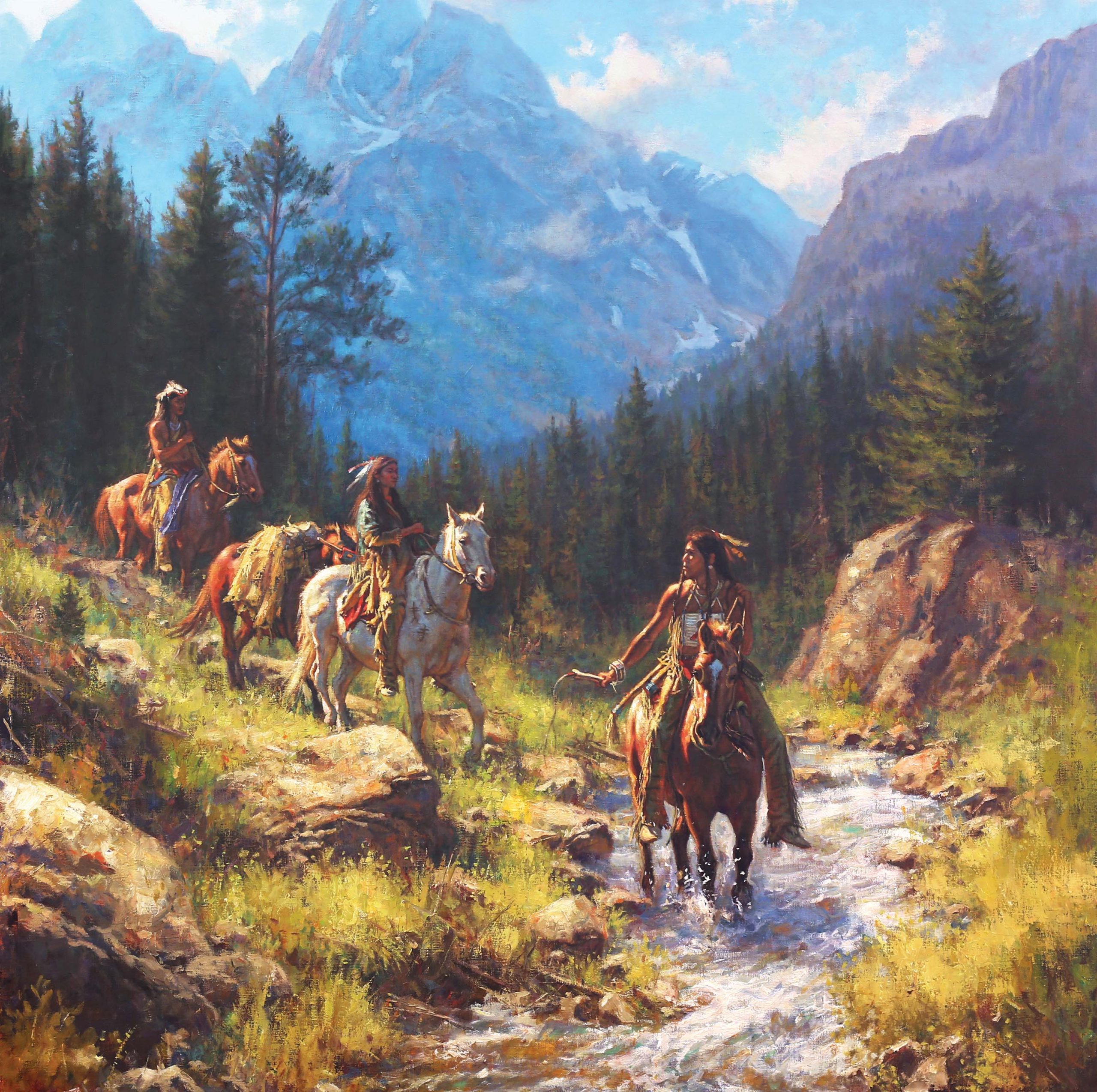

Oelze hires some of the best and most sought-after costume producers to make regalia for his live models that is indistinguishable from what Native Americans in Montana, and the Europeans who invaded their lands, actually wore in the 19th century. Pointing to a delicate buckskin dress, he explains, “To have a handmade dress like that produced, with all that beading, is at least $6,000.” Walking through his workspace is like walking back through time and stumbling upon any number of historical micro-moments. His finished paintings depict a trio of Native American scouts on horseback fording a creek in autumn, for example, or a lone mountain man confronted by a tribal party crossing a river. They are expertly rendered, such that you might expect to get splashed by the streams if you stand too close.

Oelze’s studio — which he built himself — is nestled among huge ponderosa pine and impressive rock formations that are extrusions of a 70-million-year-old geological structure known as the Boulder Batholith — a landmark famous for granitic, rounded boulders that have literally risen up from the earth. The local landforms and features seem ready-made for Oelze’s compositions, all of which effectively capture scenes that might have been common 150 years ago. High Country Rest, for example, looks as if it had been posed in the alpine — Park Lake in the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest, perhaps, or somewhere near the Tizer Lakes in the Elkhorns — the crystal waters reflecting the granite escarpment within a narrow high-country meadow.

To achieve historical realism, Oelze hires friends from the Blackfeet Nation to come to his compound near Clancy every July for a three-day photoshoot. Those photographs then serve as inspirational fodder. “During that shoot every summer, we pose the scenes and I photograph everything so that I can then paint all year,” Oelze says. “It’s a very intense, busy several days of shooting all around the property.”

Seeking Knowledge and a Clear Path | OIL ON CANVAS | 22 X 22 INCHES

John Juneau, one of Oelze’s Blackfeet Nation models, enjoys his time working with Oelze in Clancy. “Don arranges the annual shoot, and I’m just one of the models. But I also recruit other folks from the rez who know their way around horses,” Juneau says. “I look forward to it every year.”

“It’s more than just an artist-model relationship,” Oelze says. “I consider these people my family.” In fact, Juneau got his start when a cousin recruited him to fulfill Oelze’s need for skilled horsemen. “A cousin of mine modeled for him and she told me, ‘He needs guys who can ride horses,’” Juneau says. “So I started working with him, too. We’ve become really close friends. His work is spot on and as authentic as it could be. I don’t meet a lot of people off the reservation who treat me as well as Don does.”

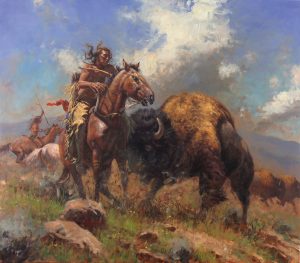

Tables Turned | OIL ON CANVAS | 40 X 46 INCHES

Because his parents were Christian missionaries, Oelze became a kind of international citizen. He was born in New Zealand and learned about America by way of his grandparents, who collected American Indian artifacts. From an early age, he was fascinated by Western mythology, cowboys, and Indigenous cultures.

When his family returned to the U.S. when Oelze was 8 years old, his interest in history — especially of the American West — only grew. “I drew and painted through high school,” he says, adding that following a year at Memphis College of Art, he finished his degree in business at Franklin Pierce University in New Hampshire. After working with a Native American who produced artwork and totems in Seattle in the early 1990s, Oelze realized that painting Indigenous people in historical settings was what he really wanted to do.

Despite his desire to paint, Oelze hasn’t always made his living as a fine artist. “I spent 10 years in Tokyo, in the high-pressure business environment of finance. The money was good, and I love Japanese culture, but I turned to painting over there as a form of stress relief.” Oelze says he’s “always been a sketcher,” but it wasn’t until 1998 that he started focusing on oils. After returning to the U.S. permanently in 2004, Oelze put his focus on art. It wasn’t long before collectors began to notice.

As Stuart Johnson of Settlers West Galleries in Tucson, Arizona puts it, “Some artists paint the West because that kind of art sells well. But Don paints the West because he absolutely loves the subject matter.”

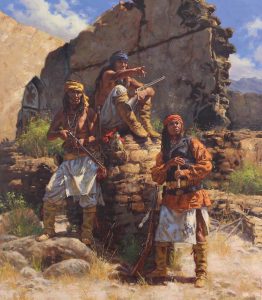

Scouts at the Old Mission | OIL ON CANVAS | 46 X 38 INCHES

Johnson especially appreciates Oelze’s fidelity to the historical narrative. (Johnson himself majored in Western history in college.) “His special talent is that he knows the subject matter extremely well — he’s immersed himself in the culture of the Plains and Southwest, and that comes across in his work. He’s really grown as an artist over the last couple of decades,” Johnson says. “Like Howard Terpning, Don composes a narrative out of the subject matter. Every one of his paintings tells a story, but it’s really the viewer who finishes the story. He depicts a specific scene, but every time you look, there is more to the narrative. That’s where Don shines as a painter — he sets up the composition so that the viewer is positioned to provide the ending of the story.”

Oelze’s scenes may be historically precise, but that doesn’t prevent him from making paintings that appear timeless, as if the artist has welded realism and impressionism in some way that captures the zeitgeist of the wilderness that persists beneath civilization’s surface.

More to the point, Oelze handles light reminiscent of an Old Master like Rembrandt, but he subtly embellishes it with the nouveau sensitivity of the likes of Maxfield Parrish. Similarly, the way he renders the motion of water is as uncannily compelling as what Katsushika Hokusai accomplished with his famous The Great Wave of Kanagawa (1831). Just as that timeless wave is eternally crashing in the foreground of a distant Mount Fuji, Oelze’s water scenes exude flow and motion in a way that seems to acknowledge what the Medieval scholars called the haecceity of things — the eternal essence of a thing that brings it to its own unique life.

Countless accomplished painters of the American West are adept at composition: Many are experts with color and light, and many are versatile imagists. Oelze is rightly among their number, but his work stands out because beyond all the hallmarks of competence and excellence, it feels alive and present. No doubt, his love of history and accuracy contributes, but Oelze’s paintings also convey an optimistic view of human nature and history that gives life to what might otherwise simply be an impressive display of technical brilliance. Or, as Johnson summarizes, “Each painting Oelze does is better than the one before.”

Aaron Parrett is a professor of English at the University of Providence in Great Falls, Montana and runs a letterpress shop called Territorial Press in Helena. He has been widely published in many fields, and his most recent book is a collection of short fiction called Maple & Lead. He lives with his wife and daughter in Helena.

No Comments