23 Nov Artist of the West: Narratives in Oils and Empathy

In an essay on the history of storytelling, writer Ursula Le Guin posits that, as a species, we have prioritized tales of adventure and action, drama and conflict. Paleolithic hunters returned not just with mammoth meat, but also — and perhaps just as importantly — with stories of risk and conquest to be told and retold around campfires, growing larger and more harrowing each time.

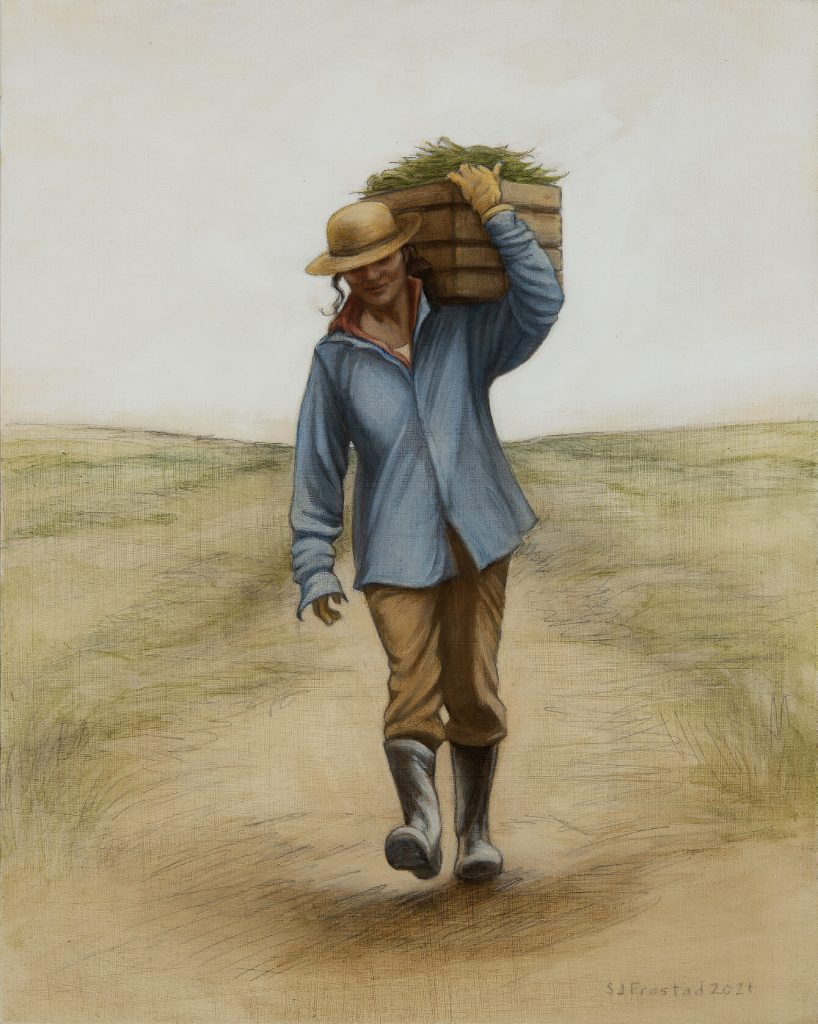

HARVESTER: BEANS | graphite & oil on wood panel | 10 x 8 inches | PHOTO BY CHRIS AUTIO

In reality, prehistoric communities relied almost entirely on the food they could gather and harvest easily nearby and with relatively little drama: grains, berries, nuts, fruits, and small game. The pursuit and conquest of a 5-ton animal makes for a rollicking story; the pursuit of a tuber does not. Put differently: We have long loved masculine stories, but have never had much time for the feminine ones.

Like Le Guin, painter Stephanie Frostad brings to her work the quietly subversive notion that these traditionally feminine stories of gathering and giving are worth hearing. “One thing that I’m interested in, generally in my work, is having people listen — especially listen to women,” explains Frostad. “And of course there’s no soundtrack to a painting, but when a group of people are turned toward a woman speaking, it kind of says in that really subtle way, that images can normalize or affirm elements of our culture — listen to her, let’s pay attention.”

HIGHER GROUND | graphite & oil on wood panel | 16 x 20 inches | PHOTO BY CHRIS AUTIO

Frostad’s delicately powerful paintings — populated largely with women, children, and animals — are grounded in landscapes that could be Montana, where she currently lives, or the eastern Washington of her childhood. Her characters harvest beans, chop wood, haul water, wade rivers, and carry lanterns across the prairie with their faces pointed into the wind. The images are rich in narrative and portent, though the storylines are rarely explicit.

“What you see on the canvas is the mysterious quality, and that has power and attraction,” says Lisa Simon, owner of Radius Gallery in Missoula, Montana, which represents Frostad. “She’s working in beauty and nature, but then there’s this other thing, and when you prod it, it’s a little sharp and pointy. Characters are often coming out of a landscape that is, in many ways, traditionally rendered, and I think that’s kind of important to the story. It’s like, here’s the West that you think you know, it’s often a beautiful West, but there are all these women delivering alternative stories and alternative histories.”

DRIFTED PATH | graphite & oil on canvas | 16 x 22 inches

Subversive though it may be, Frostad’s work warmly welcomes viewers with rich tones, bucolic settings, and wholesome-looking figures in clothing that’s both dated and timeless. “One of the sophisticated things that she’s doing,” says Simon, “is teasing out this space between beauty and romanticism, and she’s not willing to let go of beauty in order to make that break with romanticism.”

Frostad puts it in even simpler terms: “As I developed this sort of anachronistic traditional style, I thought that maybe I could keep the widest audience by making beautiful images that are easy to discern. … You don’t have to have a sophisticated education about art or history or anything else to appreciate the image aesthetically. But hopefully, the more you know, and the closer you look, there are further revelations or possibilities. I feel like beauty is a way to bring people into these other possibilities and questions.”

INTO THE DARK | graphite & oil on wood panel | 9 x 12 inches | PHOTO BY CHRIS AUTIO

Rendered largely in oil and graphite, Frostad’s work is a testament to her committed art practice. As a child, she says, “I drew and I drew and I drew. I think that drawing is actually my first love.” Then, while attending the Maryland Institute College of Art, she studied abroad in Italy and was seduced into painting. “How can you not paint when you’re in Florence?” she remarks, referencing the city’s rich artistic history. It was during this time that she began shaping her habits as an artist and making it a part of her daily life. “If I didn’t brush my teeth, I would feel odd all day,” she says. “And that’s how I feel if I don’t somehow engage with image-making on a daily basis.”

Frostad is quick to admit how lucky she feels to be able to pursue her passion for a living. “I am so privileged that I can do that. That I can get up in the morning and be quiet and go into art … serving this endeavor, and working to the greatest level of satisfaction I can, feels like a responsibility. Because I have this privilege, I really need to take care of it.”

RESERVOIR | graphite & oil on wood panel | 40 x 30 inches | PHOTO BY CHRIS AUTIO

Frostad’s devotion translates not just as a dedication to art, but also to her subjects. The people and animals in her work are rendered with tenderness and care, compassion and empathy, all made visible by brush and paint. And this is no accident; Frostad truly is empathetic to her characters and often creates work fueled by questions of social justice, environmental issues, or cultural upheaval. “I don’t know who all will speculate that far into the image,” says Frostad, “but my sense, over all these years of discussing my work with people, is that even if you can’t guess what the spark for the painting or imagery is, there’s a feeling that something significant is happening.”

RAVENOUS | oil on canvas | 16 x 20 inches | PHOTO BY CHRIS AUTIO

There’s no question that Frostad’s characters are coming to us with important messages and stories. But as an artist, her question for us is whether we’re willing to stop and listen to what they have to say.

GREEN MESSENGER | graphite & oil on wood panel | 36 x 24 inches | PHOTO BY CHRIS AUTIO

Melissa Mylchreest is a freelance writer and artist based in Western Montana. When she’s not at her desk or in the studio, you can find her enjoying the state’s public lands and rivers with her two- and four-legged friends and family.

No Comments