30 Jan Artist of the West: Kimball Geisler

Kimball Geisler paints landscapes that draw people outdoors. Whether it’s the distant peaks draped in stubborn snow or the murmur of water skimming a bend, Geisler brings the universal intimacy of nature to his work.

To be clear, he doesn’t paint portraits of landscapes; instead, he portrays concepts of nature.

“Nowadays, my work starts with an idea,” Geisler says. “I can be inspired by another painting while sitting around at home, but very often, it comes down to when I’m outdoors or driving around town, and I’ll see a shape. It won’t always be an idea about an exact spot.”

Maybe it’s the shape of a dead cottonwood tree leaning into the sunset. Maybe it’s the alpenglow on the ridge of a mountain range. Whatever the image, it tends to stay with Geisler until he can paint it.

“I noticed that, while crossing the Snake River, the leaves are changing and falling off the trees. I’m always looking out the window,” he says. “That doesn’t mean I have to drive back to that exact spot; I can see that idea in other places. An idea might be that I like the way the late sunlight overlaps the distant snow-capped hills. There’s something interesting about that kind of light.”

Once he latches onto an image or a thought that resonates, he creates a series of studies, preferably on location.

“It might be a medium painting that might work its way toward a large painting,” he says. “Not all of my paintings are going to be big.”

He needs a monumental idea for a monumental-sized painting.

“For example, if I was driving around in the desert and some rabbitbrush caught my attention, that would be a small painting,” he says. “There are always ways to turn a simple subject into something big. But simple subjects are best suited to smaller canvases.”

Sky Forms | OIL ON CANVAS | 48 X 36 INCHES

Small paintings are also a way of ideating, trying things out, arranging the elements, and finding the best way to make the subject shine.

“Ideally, everything in a painting should have a reason for being there,” Geisler says, “especially if we’re talking about composition, which is really about balance: a balance of texture, interest, detail, areas of relief, and calmness; a balance of large and small shapes. Everything that is included in the painting should reflect back to that single idea.”

Aside from painting, Geisler also conducts workshops.

“I always tell my students to stay hungry and stay in the mental space of trying to improve yourself technically,” Geisler says. “Understand there is good and bad art and try to improve yourself from that perspective.”

Winter Derelicts | OIL ON CANVAS | 40 X 50 INCHES

One big concept he likes to emphasize to his students is that value underpins everything. In art, value is defined as one of the seven elements. Value deals with the lightness or darkness of a color. Objects are seen and understood in regard to how light or how dark they appear.

“That topic gets divided into two concepts that are set against each other: form is the literal side that depicts the actual three-dimensional object, and then there’s aesthetic, or shape, which has to do with composition,” he explains. “I like to integrate things into my own framework. It’s a natural thing. I tend to really like form. I want to get to a place where shape plays a larger role in my painting. I walk the balance between form and shape.”

Jane Bell Lundgren, owner of Illume Gallery West in Phillipsburg, Montana, has represented Geisler’s work for the last 10 years. “His work is so fresh and so alive,” Lundgren says. “It’s filled with movement. His brushstrokes and the way he can combine color in a piece is remarkable.”

Over the last decade, Lundgren has watched Geisler mature and grow. “The first piece is still part of him; his spirit is woven into his work,” she says. “But he’s always striving to improve. He expects a lot from himself. Over the last few years, he’s opened up. I saw that glimmer 10 years ago, but now it’s exploded.”

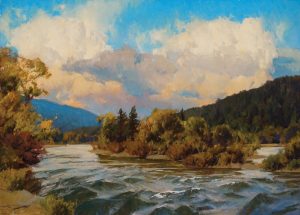

Sunset on the River | OIL ON CANVAS | 40 X 60 INCHES

His Sunset on the River is a 40- by 60-inch oil painting on canvas, a fairly large piece. The size actually adds to the immediacy of the work. The viewer, ensconced in the moment, feels knee deep in the water as if stopping while casting to take in the sunset. The placid water, mirror-like, reflects the mystery of the approaching evening.

Geisler says he “slid into painting.” He grew up in California, and then went to school at Brigham Young University–Idaho. There, he learned about the human figure and still life. Painting landscapes was something he explored outside of art school.

“Painting alone at a beautiful spot, it changed me,” he says. “So, I kept doing it. The teachers [in college] were also plein-air painters, and I was able to pick their brains and learn really important things, like form through value.”

Landscape painting presented a new challenge for Geisler, and is very different from figurative and still-life painting. “Landscape is an abstract thing,” he says. “It is all about rearranging and changing what you see. Seeing your canvas as an open field. With figurative, you are really tied to your subject. Whereas, in landscape, there is not a point where you do that. You’re on your own.”

Which may seem counterintuitive. For Geisler, placement is fluid; he rearranges the landscape to reflect his own aesthetics. He is intuitively capturing the essence of a place. “In my case, it’s about picking out things and deciding where things go,” Geisler says.

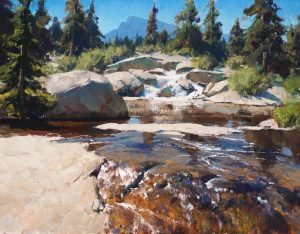

The Path it Chooses | OIL ON CANVAS | 18 X 24 INCHES

“With some people, having that kind of freedom can be disorienting, to move things in the landscape. But for me, the landscape is extremely chaotic. It’s about simplification. It’s about rearranging things to make the painting work.”

Lundgren thinks of Geisler as a quiet giant. “All of those things he has going on inside of him,” she says. “He communicates to the world through his art.”

She notes that patrons who come into her gallery are thrilled to see his new pieces. “They can feel him talking to them,” she says. “He paints the spirit and the lifeblood of a scene, rather than the sharp edges. He comes from the energy of a place and somehow translates that on the canvas.”

Freelance art writer, teaching professor, and author Michele Corriel earned her master’s degree in art history and her doctorate in American art. She has received a number of awards for her nonfiction, as well as her poetry. Her latest book, Montana Modernists: Shifting Perceptions of Western Art (Washington State University Press, 2022), won four awards, including a national award from the Western History Association.

No Comments