29 Sep Artist of the West: Call of the Wild

Surrounded by his recent work — oil paintings finished, in-process, or merely put aside — Kyle Sims focuses on painting a small fox he spotted recently in Canada. His glass palette reflects an orderly approach, a line of select hues along the top and three mixed colors in the middle of the scraped and cleaned surface. His brushes stand like flowers from bristle to sable, and they’re arranged from large to small. “I feel my life experiences have led me to be the painter I am today,” the 40-year-old artist says, turning toward his easel and picking up a purple thistle flower next to his palette. “Even meeting my wife influences what and how I paint.”

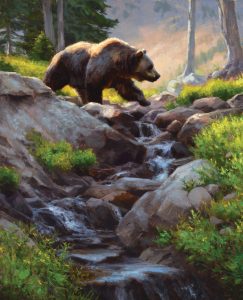

Headwaters Crossing | Oil | 32 x 26 inches

As a wildlife artist, Sims’ subjects range from bison to river otters. “I have no desire to put man into any of my paintings,” he says. “It just wouldn’t be wild anymore. The human world is my world, and what I paint is outside of that. I want to go out on an adventure with my work; I want to explore.”

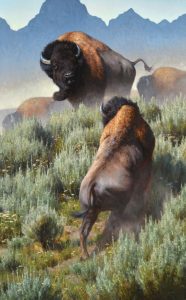

Steamy Morning | Oil | 34 x 48 inches

Sims’ paintings reflect the idea of escaping the day-to-day grind, going out onto open ranges, or bushwhacking through dense forests and rocky inclines. Sometimes the animals take center stage, but often, the landscape itself seems just as important. “I’ve always had the desire to put things down, to re-create what I see,” Sims says. These days that means incorporating the photographs he takes, and sometimes finds, into a landscape he wants to delve into. His computer screen is populated with dozens of images of bison. He points to one of his large oil paintings that features the animal with a mountain silhouette in the background. “I started with a landscape, but I imagined the bison,” he adds. “For me, art is a pleasing abstract within a world of reality.”

In a Land of Towers | Oil | 24 x 46 inches

When Sims first delved into the world of art, he spent a good amount of time in the field creating plein air landscapes. “Lately, it’s become something I do for keepsakes,” he says. “Earlier on, it was a way of training myself to determine how to paint what I saw as opposed to the image the photograph captures. Now, I go out with a camera and soak up as much as I can.”

As Sims begins a new painting, he may start with a photograph, but just as often the painting is the result of an image in his head. “I like Realism, so I use photographs for information,” he says. His inspiration comes from the masters, such as Carl Rungius [1869–1959] and Bob Kuhn [1920–2007], artists who spent years studying the animals they painted.

While Sims explains that he plans on painting a northern harrier next, the artist pulls up a photograph he took last week of one flying over some cattails not far from his home near Bozeman, Montana. The image is a bit blurry, but that doesn’t bother him. “I can work with that,” he says.

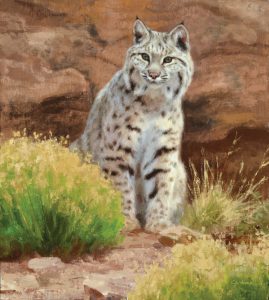

Snowcat | Oil | 27 x 44 inches

Sims also frames his own paintings in a shop located next door to the cabin that serves as his home studio. “I like doing it, and I can get it done on my own schedule,” he says. Currently, three frames sit in varying degrees of readiness, and the room smells of wood and is scattered with shavings. He starts the process by first carving out a design, usually a Celtic knot, in the corners. When the carving is done, he takes the frames into another room where he adheres gold leaf using the bole method, in which a combination of clay and animal glue is brushed onto the wood. “Once the bole is applied to the wood, I activate it through the use of water and alcohol, then, using a gilder’s tip, I apply the thin layers of gold leaf,” Sims says. Once the gold leaf attaches to the frame, Sims burnishes it with an agate stone.

Colossal Encounter | Oil | 80 x 50 inches

This past September, Sims participated in a large group show at Trailside Galleries in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, titled A Journey to the Wild. Maryvonne Leshe, managing partner of Trailside, has represented Sims for 16 years and watched him develop as an artist. She notes that his strong drawing skills help give his paintings a sense of reality. “He uses photos, but he gets out there in the woods and is familiar with the wildlife,” Leshe says. “You get a sense of that. There’s movement in his work, and you can get a feel for the animal.”

More than that, Leshe says that Sims conveys the environment of the setting. “It’s as if you can feel the temperature, the sunlight — he’s able to capture the landscape as well as the wildlife, so you understand more about the animal,” she says. “In some of his paintings, there’s more emphasis on the landscape, and in other works, it’s really a portrait of the wildlife.” She pauses as she looks around her gallery. “I’m looking at a bull elk with some females,” she adds. “They’re resting in the deep green of the woods. It’s really a natural setting.”

Tuned In | Oil | 18 x 16 inches

According to Leshe, Sims’ collectors are drawn to his work for many different reasons. “Some are decorating a room or a house, some are looking for investments,” she says. “Now that he’s been in museum shows and large auctions, his work is more valuable. Add to that he’s still a young man, and there’s a lot of development in his work and his pricing.”

Leshe notes that there are certain artists who just catch her eye, and Sims is one of them. “He’s very concerned about composition, and he’s developing into a terrific artist.”

No Comments