30 May Artist of the West: Ancestral Ties

From an early age, Montana-based illustrator and painter John Potter has treated the world — the land, the animals — as family. “The trees feel like relatives, the mountains like grandfathers,” says Potter. “That’s how I look at the natural world.” Growing up, his mother would complain that he was raised by wolves. “And I’d respond, ‘I wish I were!’”

Today, as an artist capturing scenes of the American West, Potter’s familial ties to the landscape infuse his paintings with layers of emotional depth, all tying back to the artist’s Ojibwe heritage. “I try to approach my subjects and my work through the eyes and stories of our ancestors,” says Potter. “I’ve spent so much time in the natural world in a different way, observing nature and relating to it instead of disrupting it. I never feel like I’m painting a subject — what I paint are family portraits.” The resulting works are charged with color, beauty, and questions for the viewer. What is your own relationship with nature? What role do you play in protecting this beauty?

Ancestral Ties | OIL ON LINEN | 16 X 20 INCHES

Potter’s story begins in the Midwest. Born in 1957, the artist grew up splitting time between Chicago and his family’s home on the Lac du Flambeau Ojibwe Indian Reservation in northern Wisconsin.

His love for drawing began at an early age: “My mom and stepdad gave me a sketchbook for Christmas, and that was it,” says Potter. He spent his days in the woods, sketching the region’s hills and lakes. “I would just sit down somewhere and be quiet.” Soon, the animals would acclimate to Potter’s presence and emerge. “After a while — weeks, months, and years — I began recognizing some of the same animals. I got to know their kids and their grandkids. They were like friends and relatives that I got to hang out with.”

Potter’s human family further enriched his art education. His mom’s main hobby was painting, especially impressionistic landscapes. “She was such an inspiration,” says Potter. On the reservation, he grew up watching his uncle paint scenes on buckskin hides, lacing the finished works to birch sapling frames. “I saw him painting and just thought, that’s what I want to be doing. So, he taught me,” says Potter.

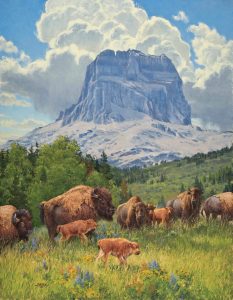

Home’s Embrace | OIL ON LINEN | 36 X 28 INCHES

Despite his love for art, Potter was discouraged early on from pursuing it professionally. His high school art teacher was critical of his skillset, warning him that he’d never become an artist. “I took her at her word. To me, she was an elder, even though she wasn’t Native,” says Potter. “She was an elder, and she was giving me life advice.”

It was enough to make him put his sketchbook away and focus on his second love, the natural world. Potter enrolled at Utah State University to study wildlife science. The new direction didn’t last long. “I realized pretty early on that the only trouble with wildlife science is that there’s science involved,” Potter jokes. Besides, without art, he felt like he “couldn’t breathe. I gave up art for two years, but I realized I couldn’t live like that.” Luckily, the university also had a great arts program. Potter switched his course load, redirecting his studies to illustration and fine art.

“Back then, conventional wisdom said that if you wanted to be a working artist, you needed to be an illustrator: get a steady paycheck, health insurance, all that stuff,” says Potter. However, after graduating from the university, the artist initially resisted pursuing opportunities as an illustrator; job offers came from a greeting card company and an animation studio, but he turned both down. “I realized I would be just another artist in a conveyor belt, drawing puppies and rainbows,” says Potter.

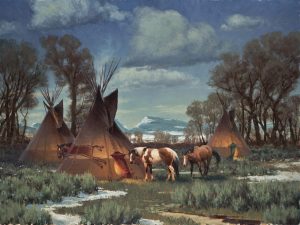

Come Home | OIL ON LINEN | 30 X 40 INCHES

Instead, following a stint at a bentonite production plant in Greybull, Wyoming — “one of the most grueling, physically demanding jobs there is,” says Potter — he joined the Billings Gazette, the largest newspaper in Montana, as an illustrator. “I was a one-person art department, drawing everything from courtroom sketches to portraits of politicians to editorial cartoons.”

Potter spent the next two decades with the Gazette. But, ultimately, he knew painting was his life’s purpose. When he was younger, his uncle gave him advice: “I remember him telling me, ‘You need to do your art. You need to educate the world about who we are as a people, who we are now, and who we can all be together if we can get back to our relationship with the natural world.’” Potter switched his focus solely to his personal art — and he hears his uncle’s words with every work he creates. “I want to inspire people to see the natural world not as something to have dominion over but to reestablish our reverence for the land.”

“John loves nature and brings it to life on canvas, creating a timeless work of art,” says Michele Couch, executive director of Santa Fe Trails Fine Art, which represents Potter. His paintings capture the world with reverence and intention, sharing scenes that draw significance from his culture. Consider Ancestral Ties, an oil-on-linen work depicting a pair of wolves diverging at the edge of a snowy forest. Potter explains the importance of his people’s relationship with wolves and their creation story of how man and wolf became brothers. “The creator sends the original man a wolf to keep him company. And he instructs man to walk the earth alongside the wolf, name everything they encounter, and establish a relationship with all they see,” Potter recounts. When man and wolf finish their task, the creator tells them to separate and establish their own families but leaves the pair with a warning to never forget their relationship as brothers. “‘Always remember that whatever happens to one of you will happen to the other,’” says Potter. “And that’s what happened in the 19th century … the wolves were almost wiped out, [Native Americans] were almost wiped out.” The story steeps Ancestral Ties in new meaning, asking the viewer to reconsider the composition of the wolves; the pair seem to be joined at the hip, a moment away from separating completely. The painting is a reminder of humans’ and animals’ interwoven fates, the survival of one dependent on the other.

Making Waves | OIL ON LINEN | 24 X 36 INCHES

Another painting, Home’s Embrace, holds a dear place in Potter’s heart. The painting depicts a group of buffalo against a stunning mountain backdrop. The group is taking tentative steps forward in a field of wildflowers — at the forefront, a calf seems poised to leap forward. Inspiration for the painting came from a photograph taken by Potter’s friend and Vice Chairman of the Blackfeet Nation, Lauren Monroe Jr. “The photo was taken [last year], moments after buffalo were brought back to and released on the Blackfeet Reservation,” says Potter. “My friend Lauren, it was his dream for years to reintroduce buffalo to the reservation.” The herd chosen for release are descendents of the very animals Blackfeet were in relationship with centuries ago; as a part of Euro American settlement, the herd’s ancestors were rounded up from land used by the Blackfeet and sent to live in Canada’s Elk Island National Park. About 100 animals were transported back to the reservation for reintroduction. Sharing Monroe’s experience, Potter recalls that when the door to the buffalo’s pen opened, none of them took off — they were unsure of what to do, uncertain of their freedom. “And it was a baby, a calf, who took the first steps,” says Potter. “It blew my mind that the younger generation was leading on the old, showing them a new way.”

Halina Loft is a writer and editor based in Bozeman, Montana. Before moving west, she worked as an arts editor for Sotheby’s in New York City.

No Comments