12 Dec Artist of the West: A Storied Past

The art of Joe Trakimas

There was a time when American children played pretend games outdoors, involving things like sticks as weapons. But not Joe Trakimas. “I never played cowboys and Indians,” says the Montana-based artist, whose fascination with Native American culture is deep-rooted, earnest, and complex. “I just played Indians. I come from two great parents who had a love and a respect for the outdoors.”

Trakimas was born in Toms River, New Jersey, a community located on a coastal estuary and rooted in colonial history. At age 9, he moved with his family to Denton, Maryland, on the Choptank River, where they lived in a farmhouse populated with his mother’s antiques, a horse, and Trakimas’ growing collection of self-made bows and arrows. “I thought there was a lot of power in making my own archery equipment as a kid,” says Trakimas, who remembers being fascinated with the Plains tribes and thinking, “Here I am making something out of nothing.”

Badger Bonnet with trade gun | oil | 36 x 24 inches

As a boy drawn to nature, Trakimas balanced his feral tendencies with an inexplicable tenderness toward the animals he hunted — his father taught him to hunt once he’d proven his mettle — and the people he imagined once inhabited the land. He found confidence and connectedness in nature, raising his fist at the suburban and urban sprawl that encroached on the woodlands and waterways he so loved.

In college at Maryland’s Towson University, Trakimas pursued his quarry in a different way: drawing and painting wildlife with absolute fealty. Ironically, he failed both art history and painting classes, then took them again and fell in love with oil painting, Impressionism, and the works of Andrew Wyeth and Canadian naturalist painter Robert Bateman.

It was then that his multiple paths — art, hunting and being outdoors, and Native American history and culture — converged. During a pre-graduation hunting trip with his father to Broadus, Montana, Trakimas felt a visceral pull to the West, knowing he needed to move here after college. He allowed himself 10 years out West, but had no idea how’d he make a living with his art.

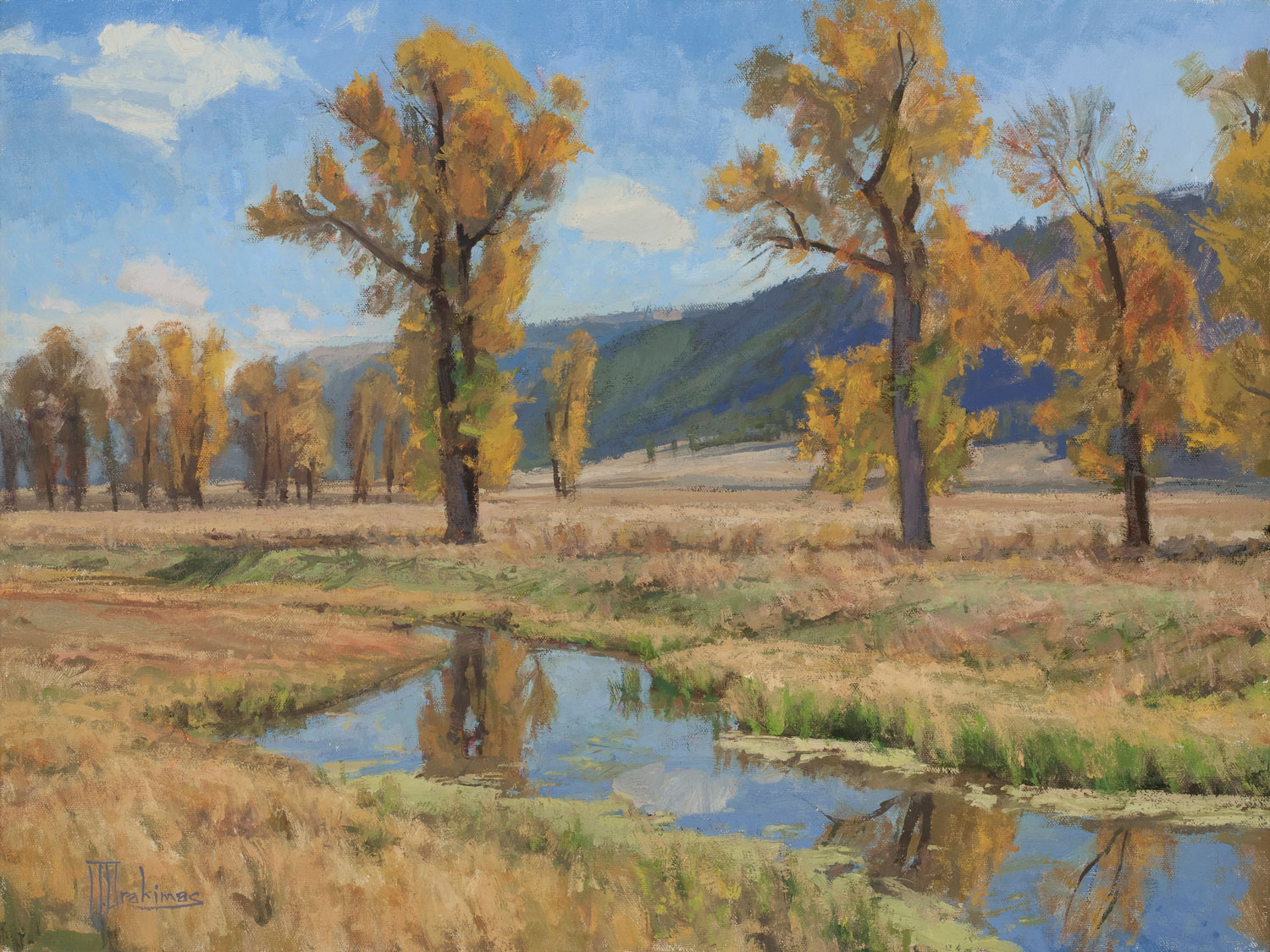

Misty Mountain Hop | oil | 18 x 24 inches

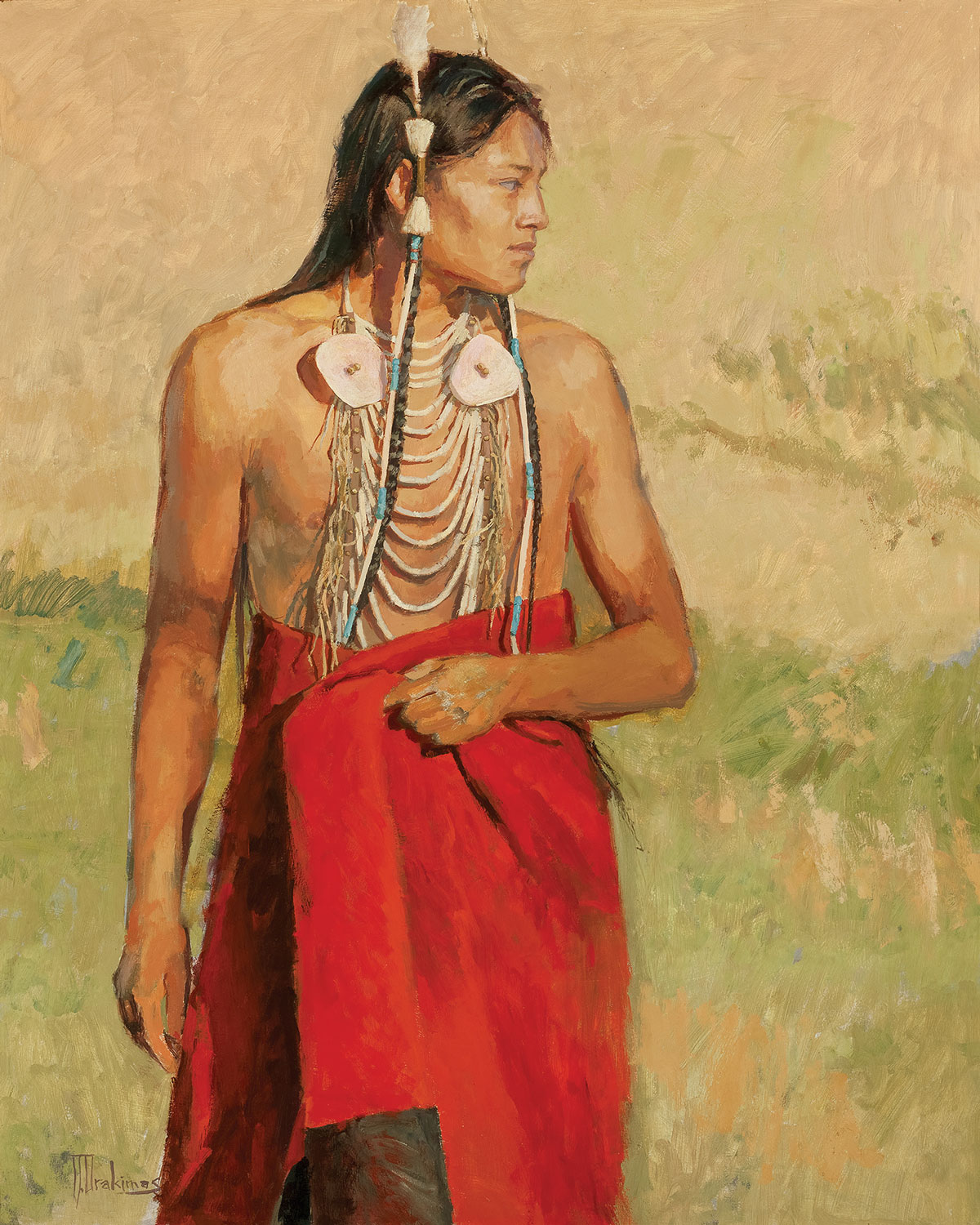

After a summer pit stop near Lake Hubert, Minnesota, to teach bow- and arrow-making at a kids’ camp, Trakimas settled in Southeast Montana. He wanted to be near the Crow and Northeast Cheyenne reservations, curious and compelled to paint something of their culture, yet also respectfully leery. “I didn’t want to impose myself on them,” he says. “I just wanted to paint, maybe a time when [Native Americans] were free,” says Trakimas, whose works point to the influence of Karl Bodmer and George Catlin.

While living in Billings, Trakimas did what many artists do: He worked other jobs, painting when he could. He was searching for a model for a particular painting he envisioned, when his then-wife suggested a man she knew from the Crow Nation — also known as Apsáalooke, Apsaroke, or Absarokee in their native Siouan language. The man and his family welcomed Trakimas to share a meal in their home, and he recalls feeling honored to paint the man’s portrait.

The Protector | oil | 36 x 48 inches

The experience was transformative. Trakimas sold the 4-by-3-foot painting through Billings’ Toucan gallery, feeling as if something was clicking into place. More paintings followed and were eventually displayed at Gallery Interiors and Tierney Fine Art in Bozeman. In 2014, he was included in the Yellowstone Art Museum exhibit, Transitions: Autumn in the Yellowstone River Valley.

Alissa Banks, founder of A. Banks Gallery in Bozeman, first experienced Trakimas’ work when she took over the former Tierney Gallery space, and she was drawn to the narrative nature of his paintings, including his titles. Lamar Elders, for example, is from a setting in the Lamar Valley in Wyoming.

“I think I’m known as a tree guy,” says Trakimas. While he appreciates the strong compositional elements that trees provide, he can’t help but attach a symbolic importance to them, anthropomorphizing them in a way. When he was hunting as a boy, he says he imagined the beech trees were elephant legs — one more fantastical element from the narrative wellspring of his youth.

Like Mark Twain’s character Huck Finn might do if he was an artist, Trakimas paints through a range of iconic scenes that collectively portray the nostalgic American West: barnscapes, cattle lazing in the shade, a Missouri keelboat, elk and other wildlife, old small-town buildings, and landscapes from Yellowstone to Glacier. “People really have a heart connection to his work,” says Banks, who will feature Trakimas in a summer 2019 exhibition. Many of the clients who are interested in his work are repeat patrons, including interior designers, she says.

Debra Shull, of the Bozeman-based Haven Interiors, loves Trakimas’ work for its authenticity. A recent placement for a client who has a “romantic fondness for everything Western,” says Shull, prompted the client to confide that “when he looks at [Trakimas’ painting], he knows he’s in his Montana home.”

Absaroka Red Robe | oil | 30 x 24 inches

Trakimas also continues to make bows, arrows, and shields, some of them informed by continuing relationships with his Crow neighbors. He then incorporates the objects into his paintings such as The Trade Gun, Split Horned Bonnet, and Absaloka Red Robe. And although he’s ever mindful of imposing or — worse — dishonoring his special bond with the flesh-and-blood embodiment of an ideal he’s long pursued, Trakimas is equally curious to learn more. He’s been paying attention to their language, he says, wondering if his purpose might include teaching others through his images and objects.

He also realizes that his own education will be lifelong and full of wonder. At the 100th anniversary of the Crow Fair Celebration Powwow & Rodeo in 2018, Trakimas enjoyed focusing on the people: talking, listening, sharing meals. He came away feeling good, feeling hopeful. “I’m glad I spent time just visiting,” he says.

A graduate of the Rutgers’ Mason Gross School of the Arts, with a master’s degree in fine arts from the University of Montana, Carrie Scozzaro exhibits artwork throughout the U.S. and writes about art, education, travel, and food systems from her Northwest home.

No Comments