24 Nov Artist of the West: A Collaboration with Material

“The ocean can be yours; why should you stop

Beguiled by dreams of evanescent dew?

The secrets of the sun are yours, but you

Content yourself with motes trapped in beams.”

— Farid ud-Din Attar, The Conference of the Birds

Large paintings lean against every available surface in the studio as Sara Mast readies for her next show. Her work has continually evolved over the course of her career, though her eye has remained focused on the planet, her heart awash in her process, and her mind set on change and reflection.

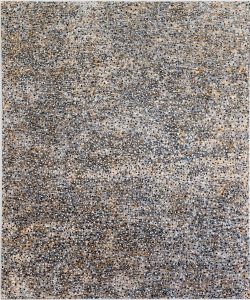

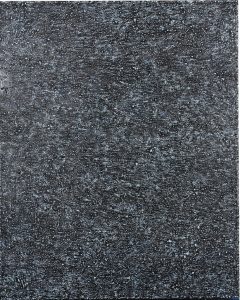

Murmur | oil, pigment stick & cold wax on repurposed canvas | 60 x 50 inches

On the work table is a large blank encaustic piece. Mast takes a sheet of graphite paper, then picks up a flat tool and moves it across the surface of the paper, pressing gray lines and abstract shapes onto the white wax. Mast then holds her small blow torch to the wax surface. A click and whoosh denote the flame’s presence. Following along the graphite lines, the heat changes the solid surface to a liquid and the lines undulate like water ripples in a light wind. A warm scent of heat, of wax, hangs in the studio — a halo of changes about to occur. Lines on the surface ghost and cling onto the encaustic as Mast then presses a piece of jagged glass into the thick, layered surface: a remnant of the past, and a beacon for the future.

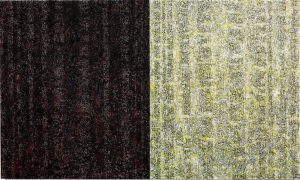

For inspiration, Mast looks to nature; for invention, she looks to science. “My intention for this body of work is to listen rather than speak,” she says, as white noise from the filtration vacuum sets a tranquil veil over the space. “As one who embraces collaboration in my work, the months of COVID-19 isolation drew me into a renewed collaboration with nature. The compulsory relationship to the digital screen demanded balance. As I slowed down enough to absorb the natural phenomena unfolding around me, I let ritual and instinct lead. Each painting is a collaboration with the material, the process, and the place — physical, psychological, and metaphysical — that I inhabit.”

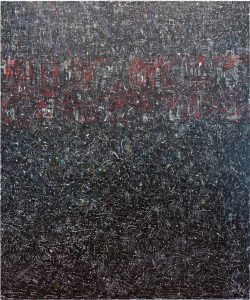

Subatomic | oil, pigment stick & cold wax on repurposed canvas | 60 x 50 inches | Photo by Ryan Parker

Mast lives and works in Bozeman, Montana, a tenured professor of art at Montana State University. Her current project involves the use of Plasma Enhanced Melter (PEM) glass. PEM, a process originally designed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, transforms human-made detritus, like plastics, into usable ethanol-type fuels and vitrified glass resembling black volcanic obsidian. The waste is melted at temperatures comparable to the sun’s surface. For Mast, the mirroring of the PEM process to nature’s energy-producing solar power is an extension of the way she approaches the environment and humans’ obligation to deal with the mess they’ve left behind. “I don’t care about expressing my opinions of what’s happening on our planet; my interest is in stepping back from human thought and opinion altogether,” she says, moving from one painting to the next — adding, subtracting, mulling, and considering. “We need a new experience, not a new ideology. My question for myself is: ‘How can I quiet the mind enough to hear the non-human voices that are asking to be heard?’ That is what I’m trying to do.”

Forest | oil, pigment stick, cold wax & ash on canvas | 60 x 100 inches

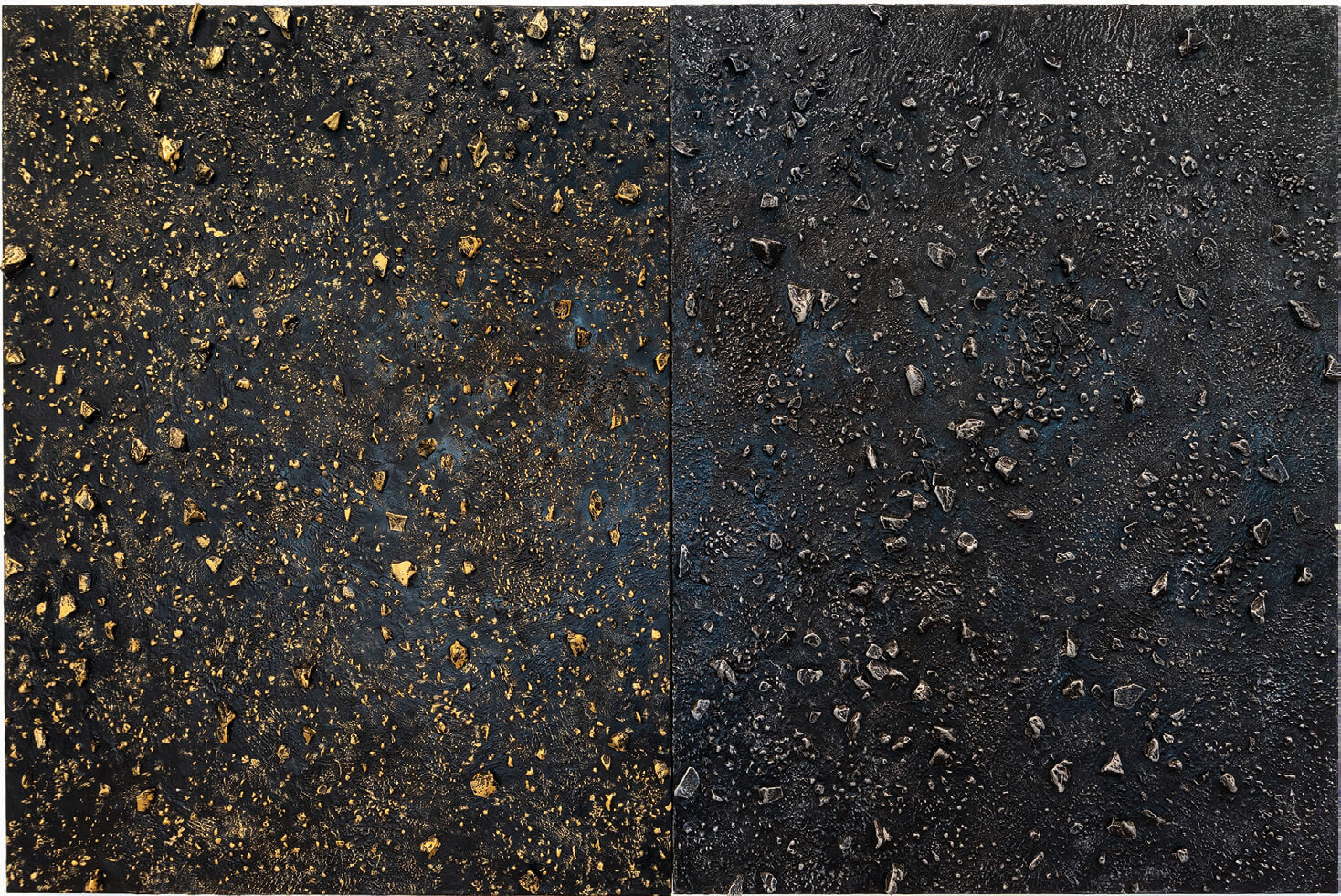

Ten 60- by 50-inch oil and cold wax paintings reflect various patterns and color — a recent medium change Mast has started to explore. Two 40- by 30-inch encaustic paintings are peppered with small pieces of PEM glass. The intricacy of the patterns pulls the viewer into the painting, almost to the point of vertigo: Like standing on a cliff’s edge, they question stance and place. As the viewer is attracted to the paintings, so too is Mast continually drawn to the natural world that inspires her work. These pieces bring together science and art in a way that combines the ugliest aspect of humanity — the degradation of the earth — with the highest form of beauty: art.

Matt Chambers of Brackett Creek Exhibitions in Bozeman, Portland, and New York has shown Mast’s work in his Bozeman space. “Everything for her is a collaborative process,” he notes. He sees her inclination to science as having that kind of peer review that art often expresses. “One of the most interesting things about her work is the way she enables the viewer to think about science in an abstract way. It gives them hope in the way good art does — a mesh of mashing anxiety for the future, but still having an aesthetic to it.”

Field | oil, pigment stick & cold wax on repurposed canvas | 62 x 120 inches | pem glass from waste | 69 inches tall

Additionally, Chambers says Mast’s work invites dialogue. “It’s slightly solution-based and it allows a larger conversation about the issues; it gives people assurance that the car is back on its wheels.”

The fact that Mast is primarily an encaustic artist, but reaches beyond her medium with a new vernacular, aptly demonstrates her exploratory nature. “She mixes her own pigment, it’s a holistic process, and it all feels like a snapshot frozen in time,” Chambers says. “As opposed to the pure encaustic pieces, the pieces with PEM glass feel like photos of a meteor shower. The encaustic is the lexicon of her aesthetics.” Mast’s recent shift to creating large oil paintings is what Chambers sees as a kind of translation. “It’s a way for her to find different solutions. You get to see the multiple steps as she adds her own topography with the gestures she knew from other types of painting.”

Juni Clark, owner and director of Aunt Dofe’s Gallery in Willow Creek, Montana, recently held an exhibition of Mast’s work. “I love the way she incorporates science, topography, landscape, the Berkeley pit, and mixes it into a beautiful random heap of abstraction,” Clark says. She considers Mast a very deliberate painter: “She thinks of every stroke, every placement of the PEM, and every movement in the wax.”

The conference of the birds (detail) | 2001, collaboration with Terry Karson and Carl Stewart | Clay, encaustic & reclaimed trash on PEM sand

“I love that she’s going big; the larger they are, the more you can lose yourself in it,” Clark adds. “Her paintings are just beautiful, and her PEM glass pieces are transformative. They take something ugly, like waste, and turn it into something not only of beauty, but something meaningful about the world.”

Tucked into a space in Mast’s studio are two trays of clay birds in “nests” made from primitive fired clay using cow manure, reclaimed trash, and encaustic that once populated the front windows of Aunt Dofe’s Gallery. This 2001 collaboration with Terry Karson and Carl Stewart references The Conference of the Birds, a Sufi poem by Farid ud-Din Attar that asks us to look at the bigger picture and aspire to higher goals — both of which Mast certainly seeks to achieve.

“The oil and cold wax paintings are done on repurposed canvases, so underneath are my paintings from the early ’90s,” Mast says. “I covered the old paintings with black paint and began by scraping back and adding new layers, using the history of the canvas (and my own past) to build a portal to a new world. When I began, I was reminded of staring at static on the TV when I was a kid — my eyes would go out of focus and my perception of the world opened up. I imagine that ‘nowhere’ or ‘nothing space’ I entered was my first meditative experience in which edges disappeared and everything felt continuous and interconnected.”

Wind | oil, pigment stick & cold wax | on repurposed canvas | 62 x 50 inches

While creating Wind, Mast knew the piece had to be a certain color, but until she discerned the movement of wind in the work, she wasn’t sure which color to use. Then, by letting her movement and intuition give her direction, the painting seemed to finish itself. By allowing her work to guide her, Mast is able to give voice to the very paintings themselves. “Lilith is about the dark feminine aspect of our relationship to the earth,” Mast says. “What does the shadow aspect have to say to me? In terms of nature, it’s saying, ‘We’re going to work together, or it’s not going to work out at all. You can’t keep abusing me the way you have. I don’t need you; you need me.’”

The essence of Mast’s work comes from her constant exploration, her push toward the unanswerable, and her drive to reach beyond traditional methodologies while maintaining a painterly practice. Through her work in encaustics, oil paint, and PEM glass, she layers questions upon questions as the viewer follows her journey beneath and above.

Freelance art writer and author Michele Corriel earned her master’s degree in art history and her Ph.D. in American art. She has received a number of awards for her nonfiction as well as her poetry and is currently working on her latest book, The Montana Modernists.

No Comments