09 Jun Ansel Adams in Yellowstone

AT A TRAIN DEPOT IN LIVINGSTON, MONTANA, photographer Ansel Adams slept fitfully on a wooden bench, 280 pounds of camera equipment piled next to him. It was June 11, 1942, and his train had arrived at 2:15 a.m. He was waiting for dawn, to get on a bus to Gardiner.

He would have preferred to make his first visit to Yellowstone in his own car, but amid the gas rationing of World War II he was forced to travel from park to park using public transportation.

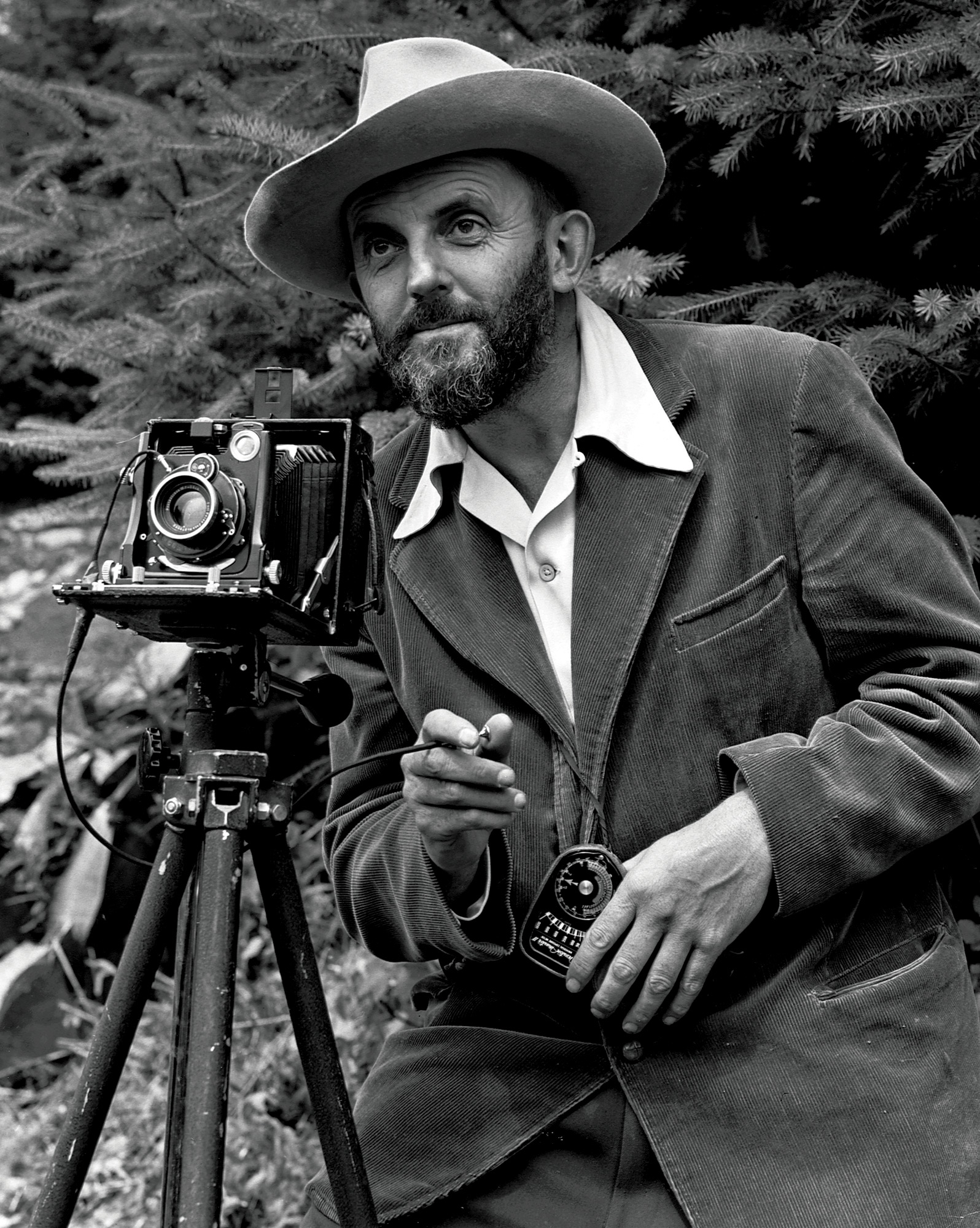

At age 40, Adams was tall and bearded, with a nervous energy and a talkative, high-spirited personality that made him seem even larger. The technical brilliance of his photography — composition, clarity, texture, and print quality — had already brought kudos from experts such as Alfred Stieglitz (who’d given him a one-man show), several books, and the occasional teaching position. With some of his most famous images already committed to their plates, he had begun to establish what would become one of the most remarkable careers in American photography. In his youth, he flirted with avant-garde techniques such as soft-focus and etching, but then he settled on a Modernist style with sharp contrast between light and shadow, given incredible precision by his large-format film. Likewise, early on he flirted with portraits, factories, and still lifes, before settling on his true passion: the outdoors.

In mid-1941, the Department of the Interior gave Adams a contract to capture images of its lands — national parks, Native American reservations, and reclamation projects — to be used as photomurals in a new headquarters building. He earned $22.22 per day, the highest rate the government could pay an outside consultant, for every day that he billed. And on every day he didn’t bill, when he used his own film, he retained ownership of the images he’d shot. It was a good contract for a struggling artist. He’d hoped for annual renewals, but then the war slashed nonessential budgets. Higher-ups told him that the project was ending and that he should proceed to shoot Yellowstone, Glacier, Mount Rainier, and Crater Lake … all in the last 20 days of June.

A student of photography and its history, Adams was aware of an earlier visit to Yellowstone by another well-known photographer, William Henry Jackson. Indeed Adams had recently visited Jackson, then 98 years old and living in New York City. Seventy-one years previously, as part of the Hayden expedition, Jackson had packed a huge plate camera and portable darkroom into the park, using pack mules and assistants to help. Jackson’s photographs had helped designate Yellowstone as a national park, but he’d been, by necessity, a mere documentarian. Ambitiously, Adams wanted photography — and Yellowstone — to plumb deeper emotions. He was after spirituality.

From Gardiner, Adams had the use of a Park Service car for himself and his gear. To capture his photos, he assembled his wooden tripod, an unwieldy 8 x 10 view camera, glass plates, and any needed filters. His light meter and famed “zone system” dictated exposure parameters — but his real gift was to marry such technical exactitude to artistic vision. Like a quarterback envisioning a touchdown pass, Adams had imprinted the final image deep in his brain long before he pulled the shutter.

Adams shot numerous photos of geysers, six of them labeled identically as Old Faithful “taken at dusk or dawn from various angles during eruption.” (He was notoriously bad at recording the times of his photographs, as if the sheer joy of artistic creation crowded out any note-taking capability.) They show billowing columns of white steam in sharp focus, contrasting with a featureless landscape and oft-cloudy skies. Clouds gave Adams magnificently complicated textures, and he must have been delighted at the possibilities of working with a form of clouds that emerged from the ground. At Old Faithful, at the placid pool of Fountain Geyser, and from vents on Roaring Mountain and along the Firehole River, rising steam suggested a fleeting momentary beauty, while the heavy permanence of the surrounding rocks and trees suggested the possibility of infinite such moments.

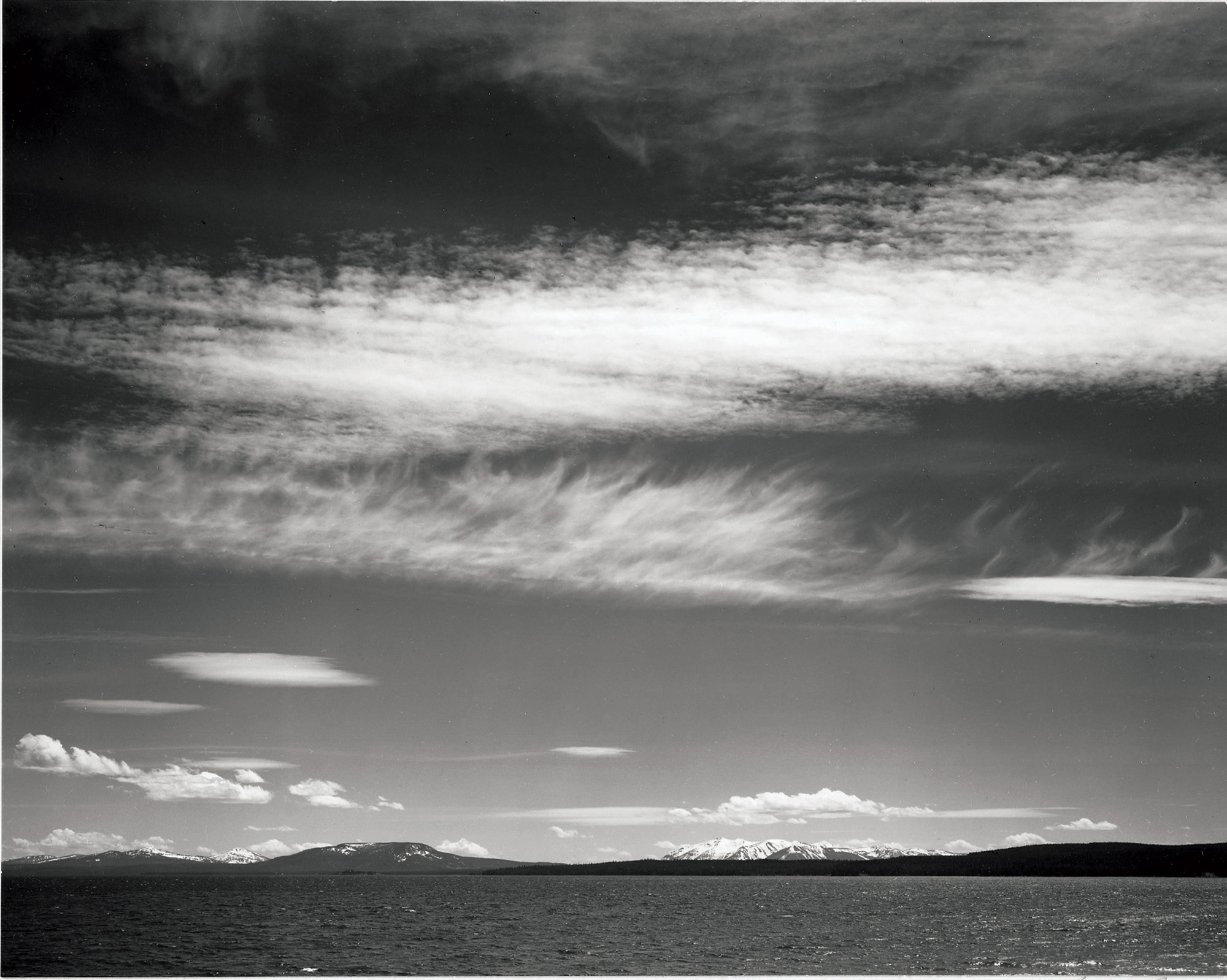

Elsewhere, Adams surveyed the terraces of Mammoth Hot Springs, made close-ups of unusually textured rocks, and depicted conventional mountain scenes near the northeast entrance. But the other Yellowstone feature that particularly captured his interest was the lake. He took several shots across the watery expanse, to snow-capped mountains pressed into distant insignificance by a vast sky. The sheer size of the lake gave a sense of the land’s epic scale, with jumbles of mountains and rivers far beyond the reach of any automobile.

None of the published photographs — 27 in the national archives, plus at least nine to which he retained copyright, now at the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona — contain people. Which is the point: As a viewer you’re alone with a geyser, a steaming pool, or a huge mountain-rimmed lake. You feel, as Adams did, redemption in solitary contemplation of the untouched beauty of the natural world. Adams loved the notion of earth gestures, as if the ground was speaking to the clouds or the horizon. As he brought you into those gestures, he made you feel a deep spiritual power.

That was an innovation in the 1940s, a time when wilderness still was seen mostly as a challenge to be endured or exploited. The outdoors was a place to toil; worship happened in a church. But when Adams showed nature’s spirituality, a good portion of the public swooned. They became seekers themselves, and were delighted by mass-market cameras they could use to mimic his visions.

That, of course, helped bring crowds to these scenes, once gas rationing ended. Adams returned to Yellowstone in 1946 on his own, and in 1948 as a celebrity on a photography workshop tour. The popularity of the park frustrated him, and in 1948 he wrote to a friend, “Yellowstone is simply horrible. Millions of people, cars, bears, garbage.”

It’s now a perennial Park Service problem: how to manage crowds seeking solitude. When by luck Adams first experienced Yellowstone in wartime emptiness, he was able to create art that captured solitude’s spiritual intimacy, the popularity of which made the solitude even harder to achieve.

But it is still possible. Walk a few hundred yards from the Lake Hotel, and you’re alone with the vast lake, the distant mountains, and your memories of how Adams demonstrated the rich wonder of that massive emptiness. Stop along the Firehole River, with steam rising from the far bank, and you see how Adams didn’t compose his photographs so much as he noticed the beauty with which nature had already composed itself. Watch Old Faithful erupt, even with strangers standing all around you, and you become enraptured by the whooshing sounds and the billowing steam and the bizarre magnificence with which nature created these inexplicable marvels. Even when crowded, Yellowstone’s landscapes are big and rich enough to provide spiritual wonder.

Adams’ great gift was to demonstrate the wonder, in ways that still prompt a yearning in all of us.

- Aerial view of Jupiter Terrace — Fountain Geyser Pool.

- Stream in foreground, with view of trees and snow on mountains — Northeast Portion.

- Old Faithful Geyser erupting.

- Lake, narrow strip of mountains, low horizon.

- Castle Geyser Cove.

- Taken at dusk or dawn from various angles during eruption. Old Faithful Geyser.

- Ansel Adams in 1947, light meter in hand.

No Comments