02 Feb An October State of Mind

It was the second week of October, just on the edge of turning weather. A cold rain had arrived a few days earlier, taking down leaves all over town. Rows and rows of damp brown mounds dotted the street gutters like small mountain ranges. The mayfly hatches had already lasted two weeks past the first night freezes. Our wasps, rendered stupid with morning cold, sat stationary on their nests, even their feelers motionless. Working early, before the sun hit the south side of the house, I scraped off a couple papery nests from inside the box that houses my sprinkler solenoids. As I worked, a few displaced wasps buzzed in circles at my feet. They didn’t know up from down at that point, body juices thickened, semi-crystallized. They dully syncopated their last waltz, the late October music winding down to the forthcoming silence of winter.

The water in the local rivers was running at good fall levels. Brown trout were beginning to push upstream toward their spawning beds. Rainbows and cutthroat were gathering fat reserves for the long winter. While most of them still engaged in some fastidious surface sipping, they were feeding heavily under the surface. The tourists had gone home. The cottonwoods along the riverbanks, still flaring here and there with yellows, had begun to look mangy and bleakly skeletal where the wind had gnawed. The geese, ducks, swans, and cranes had heeded the ghostly call of winter and set off headed south.

It was the season to throw big flies — rabbit-strip streamers, say — in a mindless rhythm of shoulder and arm, mouthing coils of shooting line, double hauling, feeling the pop of a good cast reaching its end point. This was a radically different approach than those careful mid-summer casts, with the number four line and the 12-foot leader tapered down to a 5x or a 6x tippet, and the size 16 or 18 dry fly or emerger on the end of it all, a fly so small that half the time a fellow doesn’t even know where it’s riding on the water. The summer season is hot and dainty and full of time. This fall season is big and cold, suffused with low light, and cut short by a sinking sun.

Photographed by Steven Akre

On fall nights, as I sleep, I find myself dreaming about rivers. In the mornings, as I walk the quarter mile down to our mailbox to retrieve the morning’s Missoulian, I talk to the little whitetail does that bound up from their beds in the roadside grasses and regard me with indignant gazes. I might, at any time now, see a dusting of snow up in the Rattlesnake foothills to the north. There’s a chill in the air. The kingbirds, meadowlarks, tree swallows, and bluebirds have all vanished. It’s high time to drive my old bones out to a river one more time before the snows descend.

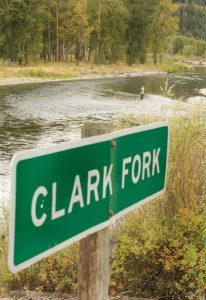

So, I wasn’t entirely surprised at myself, on a particular day in mid-October, when I decided to skip my noon book club and heed the siren summons of the Clark Fork. I almost chose the Blackfoot, Rock Creek, or the Bitterroot: Some mornings in this country I feel like Buridan’s hungry donkey driven to distraction between equidistant mangers of succulent hay. But I had not visited the Clark Fork River for a while.

I parked beside a small, red fire station with a grassy turnaround, pulled on my lightweight waders and heavy wading boots, and hiked upstream for a mile. Eventually, I arrived at the bottom of a lengthy side channel and waded out through slow, belly button-high current to a sand-and-gravel island sprouting with willows. Beetle furrows ran every which way through the sand, and elk tracks marred the expanse here and there. I was where I wanted to be, with a short spill-off at the head of the island and 50 yards of run-out. All of it was protected from the main channel where the guide boats plied. All of it was good trout water, as I knew from previous times.

The trout in October are oxygen-pumped and energetic. If I were lucky enough to hook one or two, I knew they would run. If I played them well and quickly, they would tolerate the fight and swim off, somewhat the wiser, with a quick flick of the tail. Beneath the low water, I saw the occasional flash of a moving fish.

I climbed to a high point and looked upstream, gazing down over the tops of the island willows and through the naked trees of the shoreline, seeing the bends, the eddies, the way the river linked itself together — the whole riverine gestalt. This is what I had come for, finally, and what I remembered: the sensory order of it all, the feeling that every element within the surrounding horizons is rightly ordained and justly proportioned. The air that morning seemed particularly clean and clear. During the hot days of August, smoke haze had filled the valleys almost daily as fires burned all across Idaho and Washington. September brought cleansing rains and now, in October, I could see to the farthest curvature that the topography allowed and could inhale happily to the bottom of my lungs.

I had tied up a new variant of the Prince nymph pattern for the day. I plucked a specimen from the fly box, tilted my head up so that the bifocals would work, and managed, after an inordinate number of comic failures (some of them total misses), to thread the tippet through the eye of the hook.

Photographed by Jeremie Hollman

Only a short ways down from where I began fishing, there came the familiar tug and the green back of a good trout broke the surface. It didn’t seem to understand what was going on at first, sleepy on the end of the line, then abruptly woke up and took off. The pawl in my reel announced itself with metallic screeches. An astonishing number of Canada geese, flocked on an upstream river eddy, raised their heads and gazed my way. A few of them honked, then a few more honked, and a few more, and then the whole eddy erupted with rising forms and the mixed sounds of honks and beating wings. Just at that moment the big trout, as though sensing my distraction, jagged to one side and negotiated a long-line release. The line went dead with slack, and the corners of my mouth drooped into a semi-disappointed grin.

I had had the best of it with the strike and the long run, and avoided any complications of the unhooking process which, done badly, can blacken a fishing day. So, this latest long-line release didn’t really upset me. I did miss a close look at the colors — missed knowing, for sure, whether it was rainbow, cut-bow, cutthroat, or brown — missed the completion of the act, my hand dipped into the water and fingers touching the belly. It was October, after all, the water was cold, the fish were strong. Nevertheless, I didn’t miss the sudden rush of concern, the insistent sense of existential responsibility as the trout nears morphing from a vague pulsing strength at the end of my line into the visual reality of a trout with a hook in its jaw.

Back on shore, I removed my hat, wiped my brow, and sat down on a convenient log to gather myself and watch the wheeling geese turn into tiny specks against the western cloud mass. A smell of crushed mint perfumed the air. The sway-backed white horse in the far field dropped its head to the grass. Into this quiet scene obtruded a sudden moment of realization. Time had passed quickly, the way it has a habit of doing while I’m fishing, and I realized that, at that moment, the men of my noon book club would be assembling in the upstairs room of the University Congregational Church building, pushing tables together, moving chairs around, nodding greetings to each other. And I was the hooky boy, gone over the fences of decorum to the green fields and the clear rivers of primary experience. The book was a good one that week, too, Tolstoy’s Hadji Murat. Occasionally, the group chooses one of those political diatribes from the nonfiction best-seller lists; playing hooky is no particular strain when one of those types is the fare at hand. But Hadji Murat is a novel to savor.

In my graduate school days, I once skipped a seminar with the esteemed playwright Lillian Hellman in order to go running in the salt marshes of Short Beach, just east of New Haven, checking for bluefish. Ideally, I would have met up with Lillian along some leaf-strewn trail, and we would have laced up our jogging shoes together and gone for a run, discussing a little dramaturgy along the way, a good honest sweat dripping off our brows. That’s how I would have liked the world to spin, but it didn’t. And it doesn’t.

Questions about my choices kept hovering in my head, and the only marginally clear answer I could summon was that back then in Connecticut, on my seminar date, it had been October; and in Montana, on my noon book club date, it was October, and I succumb readily to an October state of mind. In October, I believe that the true story exceeds in value the almost-true story, that the blood-pounding viewpoint exceeds in value the paginated viewpoint, and that this shoulder month soon enough turns its back to rivers and covers them in ice. October in Montana wraps itself in a gaudy and elegiac bluster, chilly in a way that tingles the heart, the skies full of winging birds, the air dancing occasionally with last hatches, and the whole of it desperately and bravely close to its final and absolute absence. This passing takes something of ourselves along with it, a happenstance that, in my view, begs immediate and personal involvement.

The white horse across the river continued moving one slow foot ahead of another to find the best grass. Meanwhile, I sat scanning my thoughts with a vague sense that the hodgepodge of the day somehow fit together — the gravel, the beetle tracks apparently going somewhere, the ghost elk, the bright fall leaves, and the big trout, exciting in its energy, but vulnerable in its hunger. And all of it was more real and important to me than the book, although I esteemed the book. In my particular world of fly fishing, physical fact and imaginative form co-exist peaceably. And maybe that was the point, because the image that held in my mind and gut — with October around me in all its expiring clarity — was Hadji Murat’s severed head in a bloody sack, finitude of the first order and not so different from a season holding golden and resplendent before the eyes, but vulnerable, ephemeral, and susceptible to storms that might, at any moment, come howling down out of the north.

I waded back into the river. There is lived experience and there is reflected experience, and the one necessarily precedes the other. Simple as that. Come evening, under my reading lamp, I would give myself over to Hadji Murat and the far off steppes of the Caucasus. But here on the Clark Fork, on my book club date, comfortable enough in my truancy, I cast out my line and fished on down through that holding water in front of me that flowed, for the moment and for not that much longer, under a clear sky and at just the optimum level. I was there, and rightly there, in the lingering last sun of October.

No Comments