03 Jun All Roads Lead to Yellowstone

“All roads lead to Rome” is a proverb from the Golden Milestone (Milliarium Aureum) that was erected by Emperor Augustus in 20 B.C.E. Located in the Forum, the monument marked the starting point for all of the roads across the Roman Empire. One hundred years ago, a similar phenomenon emerged for a brief period in North America. This time it came not from an emperor’s decree, but from popular sentiment. And the roads’ destination point was not a seat of political power but the wonders of Yellowstone National Park.

From 1910 to 1930, America went through a unique historical shift. For decades, society had been organized around railroads. A railroad’s path determined where cities would be located and which ones would thrive. A train provided the only way to transport farm products, mail-order imports, and long-distance travelers. The term “road” came to be associated with a rail road, while roads for people, horses, and carriages were commonly described with an adjective, such as “post” road or “stage” road. And many non-rail roads were simply called “trails.”

Allowing cars into Yellowstone proved central to the tourism vision of Cody, Wyoming, as demonstrated by this 1916 postcard.

Then automobiles came along. People loved them. People also realized that cars and trucks were infinitely more useful if accompanied by an infrastructure of roads that were good enough to drive on. But who would build these roads? Who would pay for the tractors and graders and coordinate the routes? The federal government, much smaller in that era, was reluctant to take on that new role. After all, railroads had been privately built — although heavily subsidized.

Initially, autos and trucks were local conveyances: They could take you to the train station, for instance. Railroad companies applauded the construction of farm-to-market roads, which extended the reach of any given station. Across the American West, county governments took the lead in upgrading and maintaining old wagon roads for local auto use.

But auto enthusiasts — and the industry that supported them — had bigger ideas. They wanted longer roads that traveled through new places and served new purposes, namely for recreation and tourism.

In 1912, Joseph W. Parmley of Ipswich, South Dakota, wanted to improve the 26 miles of dusty, marshy, gumbo-y “road” between his town and the nearby city of Aberdeen. Parmley discovered that if he could get people to think of it as more than a local road — perhaps as part of a single highway that would connect Minneapolis to Yellowstone National Park — he could gain more support. He recruited people to join an association to plan, label, and advertise this road. Eventually the project’s name, the “Twin Cities — Aberdeen — Yellowstone Park Trail,” was shortened to the “Yellowstone Trail.” Meanwhile, its route was lengthened, promising “a good road from Plymouth Rock to Puget Sound.”

The Yellowstone Trail thus became one of the earliest coast-to-coast highways. In contrast to early wagon trails (such as the Cumberland Road or the Santa Fe Trail) or military roads (such as the Mullan Road), these new roads (like the 1913 Lincoln Highway and the 1915 North-South Dixie Highway) were explicitly designed for cyclists and automobilists.

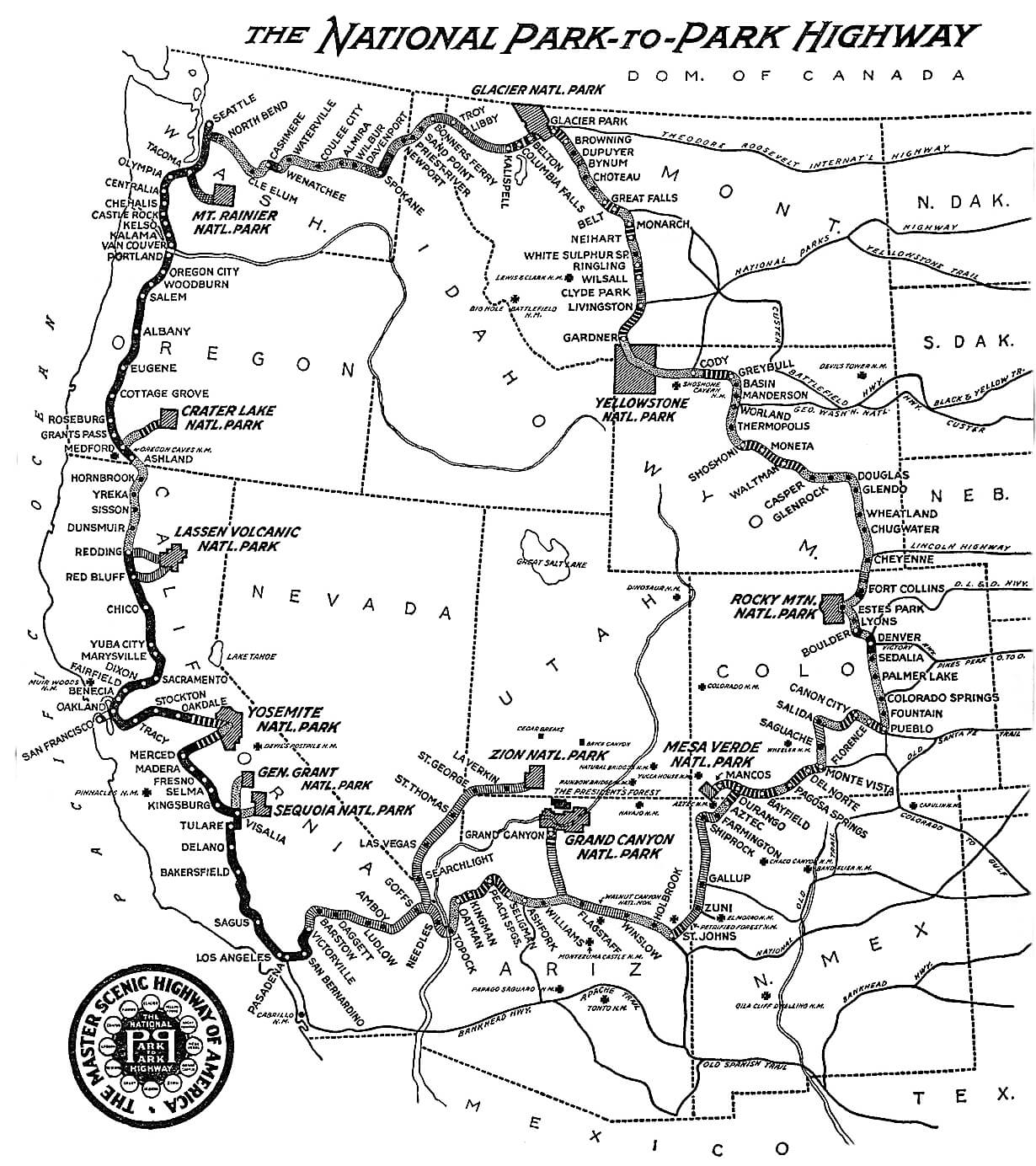

These new promotional roads often used eye-catching logos, such as this one for the National Park-to-Park Highway.

Around the same time, a different group organized another road called the Yellowstone Highway. It ran from Denver to the newly established Rocky Mountain National Park, and then through Wyoming to Yellowstone. Businesses in Cody, Wyoming — having failed to lure the Yellowstone Trail to the town’s new east entrance to the park — promoted this new road.

Ironically, before 1915, Yellowstone didn’t allow automobiles within its boundaries. For its 43 years of existence, it had always depended on horses; its internal roads were built for them, its concessionaires had invested in them, and its wildlife populations had grown used to them. Allowing automobiles would upset that delicate balance.

But the automobile-touring demand was profound. By 1915, annual U.S. sales had reached one million autos, and owners wanted to use them in national parks. On July 31, 1915, the first Model T legally entered Yellowstone. That same year, Stephen T. Mather, who was then working for the U.S. Department of the Interior to organize what would soon become the National Park Service, hosted a convention in Yellowstone to promote and coordinate these long-distance highways.

Mather was a big fan of this mode of transportation. Through the 1920s, he would tour the U.S. national parks in a chauffeured Packard with a license plate that read USNPS-1. At the 1915 convention in Yellowstone, he encouraged promoters of the Yellowstone Highway to think even bigger. As a result of their efforts, in 1920 he dedicated the nation’s “greatest scenic drive,” the National Park-to-Park Highway. Its route expanded on the Yellowstone Highway, connecting 13 national parks. From Yellowstone, it made a grand loop north to Glacier, west to the Cascades, south through the Sierras, east past the Grand Canyon, and then north to Denver. A 1922 promotional map bragged that it was “1.5% macadamized,” meaning that the remainder of its 5,600 miles were unpaved.

Meanwhile, dozens of other named roads were commissioned throughout the country. These could also be valuable for tourists traveling from other locations — such as cities in the East or Midwest — for towns hoping to cash in on that flood of tourists, and for local officials caught between small budgets and the demand for roads.

As long-distance touring increased, the support from former road allies wavered. Now cars were competing with trains rather than supplementing them. And instead of paying to improve their roads to town, local taxes from farmers now subsidized tourist jaunts through the countryside. The associations that named, platted, and promoted roads also started lobbying the federal government to pay for them.

Thus marketing became ever more important, and one great way to market a new road was to feature a tourist destination. A road through Colorado might be named after Pikes Peak, while anything farther north would be named after Yellowstone. For example, in 1915, North Dakota opened the National Parks Transcontinental Highway, which could take you from Minneapolis to Yellowstone (or, more broadly, “Portland [Maine] to Portland [Oregon]”) via Bismarck instead of Aberdeen.

A “pathfinder” car gets stuck in the mud while trying to find the Black and Yellow Trail, a route that linked the Black Hills of South Dakota and Yellowstone.

Likewise, Deadwood and then Huron, South Dakota, were headquarters for the Black [Hills] and Yellow [stone] Trail, which provided a route from Chicago to Yellowstone, and was intended to divert traffic from the more northerly Yellowstone Trail route. This road’s claim to fame emerged from a proposal at a 1924 conference to build an additional tourist attraction along its route, carving statues of historic figures into the Black Hills; the result was Mount Rushmore.

Meanwhile, the Yellowstone-themed trails proliferated: The Regina-Yellowstone trail cut south across the Montana prairie, and the Utah-Idaho-Yellowstone Highway brought Salt Lake City’s tourists to the park’s west entrance. And some roads didn’t get far beyond the organizational stages. In 1919, for example, the mayor of Bearcreek, Montana, J.C.F. Siegfriedt, planned the Black and White Trail to connect his town near Billings to Yellowstone. But rather than trying to pressure his county government to improve an existing road, he was trying to build a road through the wilderness from scratch, using local coal miners (who were on strike at the time) as laborers. After constructing 13 switchbacks up the side of Mount Maurice, he ran out of money. Similarly, the Atlantic Yellowstone Pacific Highway, headquartered in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, only commissioned a stretch from Sioux Falls to Chicago — in other words, it never reached any of the destinations evoked by its name.

Today, the idea of named roads evokes nostalgia for a higher purpose of automobile travel: to have sublime experiences on the way to meaningful destinations such as Yellowstone.

One key to both marketing and navigation was an eye-catching yet simple logo to be plastered on rocks and poles all along the route. The Yellowstone Trail, for instance, originally used blobs of yellow paint, although it later developed a stylized arrow in black and yellow. The National Park-to-Park Highway had a complex logo featuring the names of its 13 park destinations — but it was dominated by two capital Ps, one of them reversed. Many roads were named after colors to tie the name to a simple, colorful logo.

By the mid-1920s, the nation had more than 300 named roads, and some roadsides were cluttered with competing logos. The federal government increasingly came to fund road construction and maintenance, desiring a more logical nationwide road identification system. In 1926, the federal Bureau of Public Roads implemented the numbered highway system that’s still in effect today, and the numbers sometimes (but not always) followed the old named trails. For example, the old Yellowstone Trail is U.S. 12 in the Dakotas, but 312, 89, and other numbers in Montana. The numbers proved easier to remember, and their standardized signs were far more user-friendly. They weren’t as evocative as the old names — Route 66 aside — but on a nationwide scale, the tradeoff for efficiency was worthwhile. The named-highway era faded and died.

As we consider that era and its Yellowstone hub, it’s worth considering how much more popular it was than a competing idea. In 1911, Illinois Senator Shelby Moore Cullom introduced a bill to create and fund seven named national highways, totaling 12,000 miles. From Seattle, San Francisco, San Diego, Texas, Florida, New York state, and Maine, they would all converge in Washington, D.C.

In other words, it was the Roman plan all over again. When roads radiate from a country’s capital, their purpose is to act as conduits of political power. The bill died, but the idea was revived in the early 1920s with the erection of a Zero Milestone (a mile marker labeled “0”) south of the White House. Today, the Zero Milestone sits unnoticed among hordes of tourists taking pictures of the White House.

The reason Collum’s bill failed, and the Zero Milestone faded into obscurity, is that people rejected the idea of roads serving any political power. In the explosion of private-road promotion, the people expressed a different vision of what roads should be, and where they should go. They chose Yellowstone.

No Comments