14 Jul Images of the West: A Young Man’s Opportunity, The Civilian Conservation Corps of Montana

A FEW MILES FROM THE EAST ENTRANCE to Glacier National Park, along Going-to-the-Sun Road, sits Rising Sun campground. A short hike away the view opens and Saint Mary Lake appears, deep blue and glistening. Wild Goose Island perches in the middle, tiny, with its handful of trees. Little Chief Mountain towers snow-covered along the lake’s flank. The air is clear, pine-scented. Millions of people have witnessed this beloved view, the iconic vista captured in thousands of snapshots. But without a certain turn of events and the sweat of a nation, the view would have remained unseen, because Rising Sun and its trails never would have been built.

Our national and state parks are part of what defines us as a country; these cherished landscapes allow us to reconnect with the natural world and marvel at what we find there. But the protection of these places wasn’t always certain, and in the late 1920s and early 1930s, the fate of places like Glacier was unclear. Visitation to the young park dropped, the railroads lost interest in subsidizing development, and resources were thinly spread. What they needed was manpower, and the funds to support it. They needed able-bodied folks who could build campgrounds and trails, fight fires, plant trees, and put into action all the plans that the parks had outlined but could never complete. In 1933, they got more than they could have hoped for: They got the Civilian Conservation Corps.

IN THE EARLY MONTHS of 1929, unemployment in America was at an astoundingly low 3 percent. For the most part, life was good. World War I was over, automobiles were widespread, industry was booming, flappers danced and Art Deco was everywhere. Yet beneath it all lurked insidious problems, undermining society. Americans were investing heavily in the stock market, borrowing money on speculation. Outside of cities, profligate agricultural practices swept the countryside, leaving a desolate, abused landscape in their wake. The nation’s forests were plundered and mismanaged, watersheds threatened.

And then, Black Tuesday, the fateful day in October when Wall Street crashed and with it, the fate of the American people. Within three years, unemployment was officially 25 percent, but the number was likely much higher. When economist John Maynard Keynes was asked if anything like it had ever happened before, he replied, “Yes. It was called the Dark Ages and it lasted 400 years.”

Meanwhile, a man was working his way up through the ranks of government, bringing with him a certain set of beliefs about natural resources, hard work, and the American people. At age 19, Franklin Delano Roosevelt had taken control of his family’s estate at Hyde Park, N.Y., noticing a serious erosion problem caused by deforestation, he called for the planting of thousands of trees, thus slowing the loss of soil. This passion for conservation — and specifically, tree-planting — remained with him throughout his career, and in it lay the roots of the CCC.

When Roosevelt took office in 1933, the nation was in a sorry state and he knew quick action was necessary. Within days of taking the presidential oath, he convened his department heads and drew up a bill outlining an emergency conservation work program. A few weeks later, the Federal Unemployment Relief Act was signed into law, calling for a Civilian Conservation Corps. Five days later, 25,000 men were enrolled. Less than a month after the bill was proposed, Camp Roosevelt, the first CCC camp, opened in Virginia.

The premise behind the CCC was both simple and smart. As CCC historian John Salmond says, Roosevelt “brought together two wasted resources, the young and the land, in an attempt to save them both.” The program would infuse cash and workers into the areas of the country that needed it most, and create the labor force out of those who could do the most good — for themselves and for local economies. And there was plenty of manpower to be found. The CCC required enrollees to be healthy, unmarried men, between the ages of 18 and 25, and their families had to be on local relief rolls. They had to be between 5 feet and 6 feet 6 inches tall, weigh over 107 pounds, and they had to have at least six teeth. They would be paid $30 per month, under the stipulation that at least $25 of this would be sent home to family. Roosevelt initially planned to employ half a million men through the CCC. By the time the program wound down in 1942, nearly 3 million men had come through the ranks of Roosevelt’s Tree Army.

Under the joint command of the War Department, the Department of the Interior, the Department of Agriculture, and the Department of Labor, the CCC could easily have become a bureaucratic nightmare. But, for the most part, the plan ran smoothly. CCC men lived in military-style camps, and learned to cooperate, work hard, and follow orders. Often coming from wildly different backgrounds, they bonded over their common experience of poverty, and the adventure they now found themselves in. They had comrades, a roof over their heads, and ate three square meals a day — the average CCC man gained 12 pounds during his first six months with a company.

They worked five days a week, and in their downtime, played sports, made music, went to local dances, and availed themselves of CCC classes. Roosevelt was determined that no enrollee should leave a CCC camp illiterate. By the end of the CCC’s nine-year tenure, 40,000 men had been taught to read and write. Some camps held grade-school and high-school equivalency graduations. Other classes included typing, plumbing, electrical work, drafting, leadership training, shorthand, slide-rule use, physical geography, languages, and law. As they became stronger in body, they became stronger in mind.

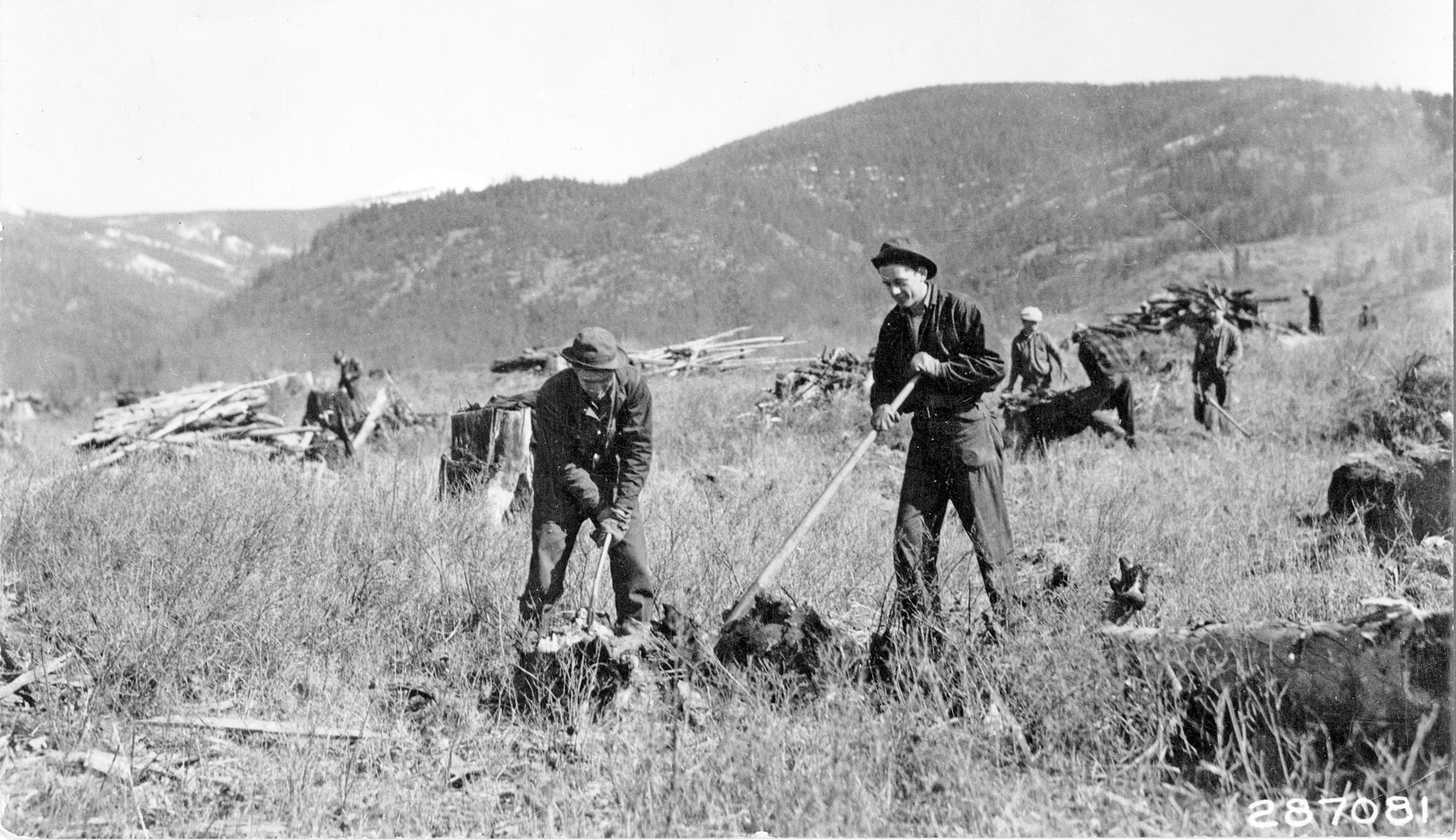

But for the most part, they toiled on the land, all over the nation. Together they planted 2.3 billion trees. They built bridges and roads and ranger stations. By 1938, 3 million acres had been developed for park use in 854 state parks around the United States. And in places like Montana, they worked to protect national forest land and bring national parks back to life.

On May 2, 1933, a train brought 108 men from Butte to Missoula. The first Montana CCC enrollees, the men gathered at Fort Missoula, waiting to be deployed to camps around the state. Soon they would be joined by men from all over the country, many from the East Coast. New arrivals from the Bronx, Brooklyn, and New York City stared wide-eyed at the mountains, getting their first taste of a life away from pavement. But these forest recruits took the change in stride and learned quickly. One man from Brooklyn, N.Y., recalled Montana fondly. “We found a glorious country peopled with some of the most hospitable people in the world. It took a little time to become accustomed to trees instead of people … We were given plenty of hard work, which, with regular meals and rest, as a part of camp discipline, we became stronger.”

They made the landscape stronger as well. In Region One of the U.S. Forest Service (which covers Montana, North Dakota, and small portions of Idaho, South Dakota and Wyoming) CCC crews built more than 2,500 miles of roads; erected 44,184 signs, markers and monuments along roads and trails; seeded or planted trees on nearly 30,000 acres; treated roughly half a million acres of white pine for blister rust; built 93 lookout towers; strung hundreds of miles of telephone line; and spent 372,000 worker-days on forest fires.

This last task — fire suppression — proved to be the CCC’s most important role in Montana. Before their arrival, the fire-fighting programs on much of the national park and forest land was inadequate, and access to remote regions was nonexistent. In between fighting blazes, the crews set to work cutting trails and fire access roads into the area’s forests. Soon they had developed elite “flying squads,” well-equipped, well-trained, 25-man, mobile fire crews who could be ready at a moment’s notice. In these teams were the foundations for today’s hot shot crews.

Many of the incoming men arriving from around the country were sent to Camp Nine Mile, in Alberton, Mont., adjacent to the remount depot of the Lolo National Forest. This camp — one of the largest in the nation with 44 buildings and the ability to house 600 men — eventually became a staging ground for companies arriving and awaiting assignments to one of the state’s 37 camps. Here, the effectiveness and capacity of the CCC became apparent. Not only did they handle the usual tasks of road and bridge building, tree planting, and fire suppression, they also raised and tended to the needs of the herds of pack horses and mules that were used by the Lolo National Forest. CCC men learned to repair horse tack and make saddles for the pack strings of animals that would carry supplies high into the mountains. Nearby in St. Regis, at the CCC-built Saranac Nursery, 12 million seedlings grew each year, to be planted throughout the state.

While all camps had their roles, the projects in Montana’s national parks seemed extra special. Agencies worked together to ensure the highest protection of natural resources — and the natural beauty — of these landscapes. They were careful where and how they built roads and trails, planted trees to reforest areas and protect the watershed, and helped keep fires controlled. They built lecture circles and campgrounds, hoping that future generations would come visit the parks and learn about their wonders. Many CCC alumni say with pride, “We were the first environmentalists,” and feel that they helped spark a national environmental ethic through their work. And it is because of them that the people of a nation are able to go out into these protected places, with an appreciation of nature that has been handed down.

Many CCC camps had newspapers, and Fort Missoula was no different. In their paper, called the Green Guidon (the cost of which was “one smile”), a leader sums up the experience and the value of the CCC after spending a season in Yellowstone Park with his company: “We have a lasting edifice here, to hard work and industry. We have had the privilege of watching an infant grow to manhood, so to speak. And joke as we may, life is going on just as happily here as we could hope to find it most anywhere. The trials and hardships of building a new camp have cemented friendships of 200 boys … into bonds of comradeship rare and hard to duplicate. They seem to know that only by working and pulling together can they hope to achieve.” Pulling together, they made a generation, a nation, and its land stronger.

No Comments