05 Oct A Profile of Obsession

ELLIOT GARFIELD IS A MAN OUT OF TIME.

Not hourly time, though as a UPS delivery driver, he is in a perpetual dust cloud of a hurry on his route of graveled Northeast Montana backroads. And not seasonally, though he can seem time-deprived as he rushes breathlessly from ice fishing to shed-antler hunting, then open-water walleye fishing on humid summer evenings, and finally to bowhunting giant mule deer and elk into the fall.

Not hourly time, though as a UPS delivery driver, he is in a perpetual dust cloud of a hurry on his route of graveled Northeast Montana backroads. And not seasonally, though he can seem time-deprived as he rushes breathlessly from ice fishing to shed-antler hunting, then open-water walleye fishing on humid summer evenings, and finally to bowhunting giant mule deer and elk into the fall.

No, Garfield is misplaced in an epochal sense. He should have been born centuries ago, in an era with fewer rules and roads and an uninhibited allowance to hunt and gather. Garfield, an enrolled member of North Dakota’s Turtle Mountain band of the Chippewa tribe who lives in a split-level house overlooking Fort Peck Reservoir, would have been his tribe’s great shamanic hunter. Songs would have been written about him, and his prowess at killing animals made legend and then passed down across the generations. Hell, they would probably have named a constellation after him.

As it is, Garfield, age 42, is as close to a hero hunter as you can get in an age of next-day delivery and Snapchat. He’s a local legend for his success as a hunter and angler, for his uncanny ability to conjure huge mule deer out of what can look from a distance like empty, bleak lands, and to catch sowbelly walleye when accomplished anglers around him nurse a day’s skunk.

As it is, Garfield, age 42, is as close to a hero hunter as you can get in an age of next-day delivery and Snapchat. He’s a local legend for his success as a hunter and angler, for his uncanny ability to conjure huge mule deer out of what can look from a distance like empty, bleak lands, and to catch sowbelly walleye when accomplished anglers around him nurse a day’s skunk.

But as his tribal ancestors might have also experienced, his achievements have been clouded by criticism and doubt. How could he be so routinely successful if he wasn’t bending or breaking rules? How does Garfield consistently find outsized animals that are overlooked by the rest of us?

The answer is both simple — he’s far more persistent than any other hunter I know — and complicated. Like many people in pursuit of a narrowly defined goal — Major League pitchers, first-chair violinists, vice principals — Garfield is fueled by a powerful mix of ego, pride, curiosity, and fear. In Garfield’s case, add admiration for wildlife that drives him to hike another mile, to spend another hour drifting jigs, and to watch just one more buck on a distant ridge.

But Garfield is also an apex predator. Would you ask the wolf why he hunts?

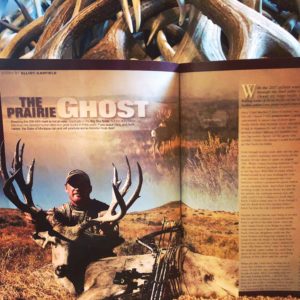

Of course, wolves don’t have Instagram accounts. Garfield’s feed is full of selfies, his square bewhiskered jaw grinning behind the biggest mule deer shed antlers you’ve seen, gigantic Missouri River walleye, and all variety of enormous elk, mule deer, and pronghorns.

Elliot Garfield’s Instagram photos offer a glimpse of his obsession with hunting and fishing.

Social media reveals one great paradox of Garfield: He’s an intensely private person who nonetheless feels compelled to promote himself and his achievements, which he does every time he shows off another whopper. As a member of the fairly small community of hunters in Northeastern Montana, I had heard about Garfield before I met him, and his reputation was always qualified, partly because of his relentless flamboyance. “He’s always eager to tell you he got the biggest buck, but he can’t — or won’t — always tell you the details,” was one hunter’s observation.

I heard similar descriptions of Garfield during the time I worked for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks out of Glasgow. Game wardens’ suspicions that he was cutting corners were aroused a few times during my tenure, but whether they culminated in investigations of Garfield, I never heard. “For a couple seasons in a row, Elliot got his archery bull just a little after sunrise on opening day,” says Luke Strommen, a long time Glasgow bowhunter who is also a Valley County deputy sheriff. “A lot of people, including me, questioned how he could achieve that. But here’s the thing about Elliot. Once he finds an animal worth his time, he stays with it until he gets it. He puts in the time before the season, and then basically sleeps with the animal until he can kill it.”

I heard similar descriptions of Garfield during the time I worked for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks out of Glasgow. Game wardens’ suspicions that he was cutting corners were aroused a few times during my tenure, but whether they culminated in investigations of Garfield, I never heard. “For a couple seasons in a row, Elliot got his archery bull just a little after sunrise on opening day,” says Luke Strommen, a long time Glasgow bowhunter who is also a Valley County deputy sheriff. “A lot of people, including me, questioned how he could achieve that. But here’s the thing about Elliot. Once he finds an animal worth his time, he stays with it until he gets it. He puts in the time before the season, and then basically sleeps with the animal until he can kill it.”

Garfield bristles when I asked him about bending the law, either its spirit or its letter, in pursuit of trophies. “I’ve been misunderstood all my life,” he says. “I’ve been called everything from a poacher to a cheater. But I’ve never been a poacher. I’ve respected the land and the animals. I can’t help it if most people treat hunting like a season. For me, it’s not a season, it’s a year-round thing, from finding shed antlers, to scouting, to hunting, to watching what animals survived the winter and where they drop their antlers, and back around again. It’s a way of life.”

Then he unspools an autobiography that gets at the germ of his obsession, the rewards it has brought him, but also its costs in terms of domestic intranquility, a bruised reputation, and career. “I can say without arrogance that I’m blessed when it comes to hunting,” Garfield tells me. “I feel like I have an innate ability to get close to animals. God gave me a little talent, but the rest is earned. You could drop me into an entirely new landscape, and I feel like within a short time I’d learn it and figure out how to hunt it effectively.”

Some of his ability may be innate, but much of it was learned from five uncles who invited young Garfield to their annual elk camps in the Missouri River Breaks. “One of my earliest memories is with my oldest  uncle Dan — they called him Cowboy. He died last year,” says Garfield. “I was just 8 or 9, sitting with Cowboy in a pickup way back on a ridge in the Breaks, waiting for my dad who was trailing a bull he had hit in the shoulder blade and couldn’t find. I was crying because I missed my dad, but Cowboy looked over at me and told me, ‘You’re going to be the best bow hunter that ever walked this land.’ That stuck in my head. I have always tried to live up to that.”

uncle Dan — they called him Cowboy. He died last year,” says Garfield. “I was just 8 or 9, sitting with Cowboy in a pickup way back on a ridge in the Breaks, waiting for my dad who was trailing a bull he had hit in the shoulder blade and couldn’t find. I was crying because I missed my dad, but Cowboy looked over at me and told me, ‘You’re going to be the best bow hunter that ever walked this land.’ That stuck in my head. I have always tried to live up to that.”

Garfield followed the family tradition of hiking, often farther and harder than anyone else in the county, and managed to kill two 6-point bulls while he was still in high school. “I shot a shitty bow, an old Ben Pearson compound with recurve limbs that were duct-taped because the limbs were cracked. But I practiced with that bow every day of my life. I never went for school sports, because I was either fishing or scouting or hunting. But I learned how to bow hunt big bulls. It’s public land, and you have to deal with every other hunter and learn how to use hunting pressure to your advantage. You have to know the land and where the animals will go when they get pressured. Usually that means you have to hike farther than anyone else, including the elk. I think I’ve figured some things out; I’ve killed 19 bulls with my bow.”

Garfield followed the family tradition of hiking, often farther and harder than anyone else in the county, and managed to kill two 6-point bulls while he was still in high school. “I shot a shitty bow, an old Ben Pearson compound with recurve limbs that were duct-taped because the limbs were cracked. But I practiced with that bow every day of my life. I never went for school sports, because I was either fishing or scouting or hunting. But I learned how to bow hunt big bulls. It’s public land, and you have to deal with every other hunter and learn how to use hunting pressure to your advantage. You have to know the land and where the animals will go when they get pressured. Usually that means you have to hike farther than anyone else, including the elk. I think I’ve figured some things out; I’ve killed 19 bulls with my bow.”

Garfield says he should hate hunting and fishing, considering how intensely his extended family threw themselves into the activities. “My uncles and I would still be out fishing the Big Dry Arm of Fort Peck when the waves were so heavy that every other boat was off the lake,” he says. “We’d be hunting whitetails at 30-below, when I’d be so cold I couldn’t feel my feet or my fingers.”

But all that time in the field taught Garfield the lay of the land, a capacity for pain and physical discomfort, but also the upper limits of the size of fish and wildlife that  Northeastern Montana is capable of producing. Garfield started hunting by himself, testing his abilities to turn up the largest bulls, bucks, and fish in the region.

Northeastern Montana is capable of producing. Garfield started hunting by himself, testing his abilities to turn up the largest bulls, bucks, and fish in the region.

His father, Leon Garfield, anticipated his son’s stature as the community’s most accomplished hunter. “Some of my brothers were pretty intense hunters, but nobody has the intensity of Elliot,” says Leon. “He passes a lot of animals that other people would be happy with. But when he decides it’s an animal he wants, he’s like a coyote. He doesn’t give up until he gets it.”

That intensity has a cost. Garfield says he doesn’t spend as much time as he wants with his two teenage daughters, who he has been raising since getting custody from their mother. His single-minded focus on being in the field probably limits his prospects to being promoted out of the box-delivery side of UPS. And I experienced it firsthand, trying to arrange to interview and photograph Garfield for this story. He stood me up three times — opting to fish for big Missouri River and Fort Peck Reservoir walleye rather than stand for a conversation — before we managed to meet up. No one else in my world has such little regard for appointments or social norms.

That intensity has a cost. Garfield says he doesn’t spend as much time as he wants with his two teenage daughters, who he has been raising since getting custody from their mother. His single-minded focus on being in the field probably limits his prospects to being promoted out of the box-delivery side of UPS. And I experienced it firsthand, trying to arrange to interview and photograph Garfield for this story. He stood me up three times — opting to fish for big Missouri River and Fort Peck Reservoir walleye rather than stand for a conversation — before we managed to meet up. No one else in my world has such little regard for appointments or social norms.

It made me wonder: What other societal norms does Garfield eschew? Is there any merit to the back-of-hand whispers that Garfield has achieved his success by staying just ahead of the law?

In some ways, that’s an unanswerable question, although Strommen acknowledges that early in Garfield’s trophy-hunting career, when he was focused on the biggest whitetails the Milk River could produce, Garfield probably crossed fences he didn’t have permission to cross. “When he was younger, I know Elliot had a reputation for trespassing, whether for deer hunting or shed hunting,” says Strommen. “I witnessed that firsthand. I don’t want to get into details, because it’s not important now. What’s important is that people change, and I firmly believe that Elliot has changed. As for being a good hunter and understanding the game he’s chasing, I don’t think there’s anyone better. He’s the most ate-up hunter I’ve ever met, whether you’re talking trophy whitetails or mule deer or shed hunting.”

Shed hunting now consumes Garfield with an intensity that burns even hotter than killing the animal that owned the immense antlers he finds. “I believe that the biggest challenge of our times is finding matching world-class mule deer sheds on public land,” says Garfield, who owns only one rifle and a handful of bows. “That’s the bar. If you can do that regularly, you’ve really done something.”

Garfield’s hunt for shed antlers consumes him almost as much as the animals themselves.

Garfield’s hunt for shed antlers consumes him almost as much as the animals themselves.

Garfield possesses many matched sets of 190- and 200-class mule deer that he’s picked up; and a good indication that he’s adopted a philosophical perspective to hunting is that he’s become a collector, mainly of record-class mule deer sheds and antlers of deer killed generations ago.

He displays these legendary racks in what amounts to a shrine to trophy animals on the ground floor of his house. Here’s a 36-inch buck killed north of Saco in the 1960s. There’s a record-book whitetail killed by a Scobey-area farmer a generation ago. He can recount every detail of every antler in his house: the date, score, location, and other salient nuances. That includes the hundreds of shed antlers that he has found just in the last year or two.

Shed antlers represent the past. They’re evidence of an animal that may or may not still be alive. I ask Garfield if he’s happy simply picking up these past-tense artifacts. He smiles and shows me his phone. On the screen is a blurry, long-distance photograph of what I can barely make out as a mule deer buck with tall and wide antlers that look like a medieval candelabra.

“That’s the biggest typical buck I’ve ever seen, and I’m so sure I’ll kill him that I’m not even scouting,” Garfield tells me. “I know where he lives, and I know his habits. When I go for him, I’ll drop everything else and go for him. No idea how long it will take, but I’ll get him.”

No Comments