24 Jul Images of the West: A Daily Reminder

From the personal diary of Elling William Gollings

June 2, 1920

The wild frontier of America was vanishing after decades of Western Expansionism. A handful of significant artists recognized this fact and from the early 20th century, they dedicated their lives and art to recording an era of history that could otherwise never be reclaimed. C. M. Russell was one of the earliest who had lived the cowboy way and chronicled scenes from his experiences. Two other artists who were frantically attempting to go West before it was gone were Elling William “Bill” Gollings [1878-1932] and Hans Kleiber [1887-1967].

Though he was born in Idaho, Gollings was educated at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts; he finally returned to find the Old West in its final years. He had worked on ranches in Nebraska, South Dakota and Wyoming, eventually settling in Sheridan, Wyo. The German-born Kleiber, who also settled near Sheridan, traveled the Northwest working as a ranger for the U.S. Forest Service. The two came from different backgrounds but were united in their passion for the wild country where they lived and painted it with reverence. They developed an enduring friendship and their careers were inextricably linked as a result.

Though Gollings was known for his accurate depiction of detail in everyday scenes on the Western frontier — from bucking broncos to Indian ponies grazing near teepees on the open range — the particulars of the artist’s own daily life remain spotty. But in reading his personal diaries from 1915 to 1931, the picture of a resilient artist dedicated to his pursuits emerges. Humble in his demeanor, Gollings was well known in the cowboy world for his knowledge of the West. So much so that he was often asked to judge events at various local rodeos.

DURING MY CAREER AS AN ART dealer and historian, I have researched the life of Bill Gollings, trying to fill in the gaps. Last fall, a call from a wonderful lady set a course of events in motion that changed the direction of my historical art detective work. The phone rang and a woman’s delicate voice asked if I would consider buying some etchings by Bill Gollings. I was at work on a third book about the artist and immediately responded: “Yes!”

This prospect proved to be unusual. As it turned out, the woman on the phone and I shared common acquaintances in her hometown of Birney, Mont., where her grandparents Leonard Kruidenier and Mary Gordon Collings Kruidenier met and later married. Leonard had partnered with Percy Cox in the cattle business in Birney, which also happened to be the place where my wife, Marylee Moreland, was raised. The lady explained that she wanted to sell various items of her grandmother’s. In addition to the artwork, she had a photograph album and correspondence from her grandfather dating back to the early 1900s.

Later in the fall, through continued research, I discovered the handwritten diary kept by Bill Gollings from 1915 to 1922. It was not daily entries but simply notations in a small notebook. Though I had worked from a typed version of this journal in the past, seeing and thumbing through the handwritten pages meant much more to me.

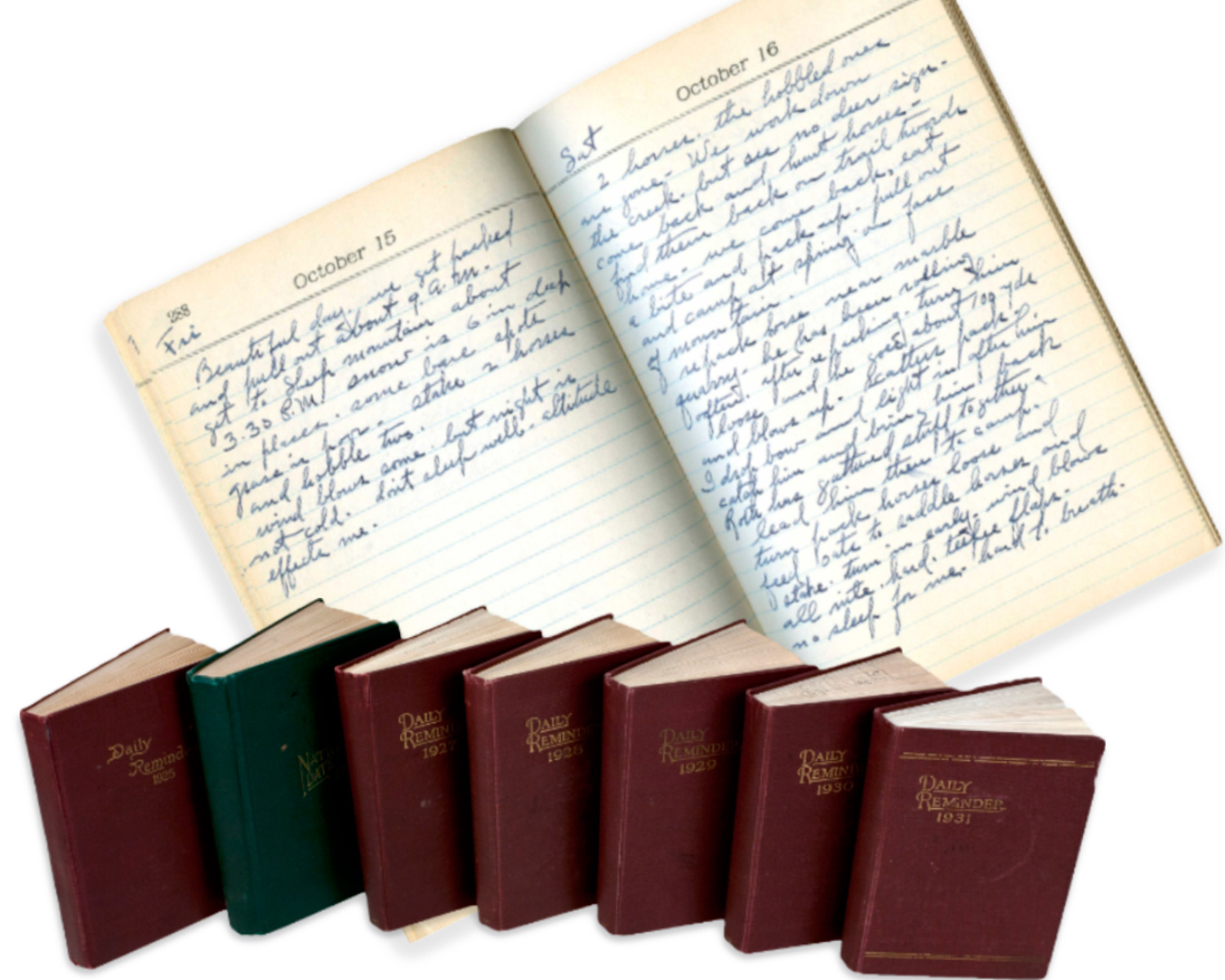

Soon another piece of evidence added to my research; I could just see old Bill Gollings smiling as I discovered it. A source had borrowed seven years of Gollings’ Daily Planners, from 1925 to 1931. I immediately scanned the journals into my computer, grateful for the privileged viewing.

In the world of research, one will find bits and pieces. Over time, I had amassed a large photograph collection, personal letters and almost 14 years of handwritten diary entries, all having belonged to Gollings. These materials introduced me to a period of history in Montana and Wyoming from nearly a century ago.

Carefully and respectfully, I opened the small bound books, feeling as if — after years of research — I was discovering a true friend. Gollings did not have a lot of family, but instead centered his thoughts and processes on his artwork. While an intense artist, Gollings wrote with apparent ease in his diary about his experiences outdoors and the West that was changing before his eyes.

October 15, 1926

“Beautiful day. We got packed and pull out about 9 a.m. Get to Sheep [M]ountain about 3:30 p.m. Snow is 6 in[ches] deep in places. Some bare spots. Grass is poor. Stake 2 horses and hobble two. Wind blows some. But night is not cold. Don’t sleep well. Altitude effects me.”

October 16, 1926

“2 horses. The hobbled ones are gone – We work down the creek. But see no deer sign. Come back and hunt horses – find them back on trail [toward] home. We come back, eat a bite and pack up. Pull out and camp at spring on face of mountain.

Repack horse near marble quarry. He has been rolling often. After repacking – turn him loose and he goes about 100 yds and blows up. Scatters pack. I drop bow and light in after him catch him and bring him back. Roth has gathered stuff together. Lead him there to camp. Turn pack horses loose and feed oats to saddle horses and stake. Turn in early. Wind blows all nite hard. Teepee flaps[,] no sleep for me. Hard to breath.”

FROM APPROXIMATELY 1896 to the 1920s, the country of southeastern Montana and northeastern Wyoming was a virtual beehive of activity. Just after the turn of the century, four people from different parts of the world would meet in Sheridan, Wyo., then a booming railroad town. The first was Leonard Kruidenier who came out West from Iowa around 1906. Letters to his mother showed his excitement for this new country. Kruidenier eventually, as mentioned earlier, was in the cattle business in Birney, Mont.

Leonard writes to his mother on June 21, 1906:

“As I wrote from Forsythe, I had hired out to a rancher seventy-five miles from a railroad. … It took three days to make the trip, so you can imagine I saw some pretty rough country. Reservation right across the Tongue river and I see Indians galore.”

The second was Mary Gordon Collins from Mississippi, who became the school teacher at Birney in 1914. As a single female on the frontier, she was a rare commodity. Collins became a frequent guest to the nearby Bones Brothers Guest Ranch, where she met Leonard. The two were married in 1916.

Just before the turn of the century, from a ridgeline above Rosebud Creek, young Gollings could see the little homestead of his brother, DeWitt Gollings. This was the open range of Montana and Wyoming, territories that had recently been granted statehood in 1899 and 1890, respectively. After a brief visit, his brother staked Gollings a fresh horse, and he eventually settled in Sheridan, Wyo., in 1907. Even as Gollings continued to work on ranches throughout the region, he built a small art studio in Sheridan. In art school he had learned to work in oil and watercolor, both of which he used to portray his personal experiences living the cowboy way. His cowboy pals nicknamed him “Paint Bill.”

Meanwhile, Hans Kleiber had arrived in Sheridan by train in 1904. With two large mines in operation, the expanding railroad and a growing population, the bustling community was ripe with opportunity. Kleiber had come to Wyoming to become a forest ranger. Eventually painting and etching overpowered his forestry career. Kleiber encouraged Gollings to take up etching as well. Finally in 1925, Gollings was persuaded it was a viable avenue for his career. It was a way to make his work accessible to clients at a lower price range than his paintings.

Ultimately, these four people’s lives crossed paths. Leonard Kruidenier knew Gollings as a cowhand who did artwork. But it was Will James, the artist and writer of Charles Scribner’s Sons fame, who brought them all together. James met Gollings when he came to Sheridan in 1925 (James later bought a ranch near Pryor, Mont., in 1928.). That same fall, James took his wife to Lame Deer, Mont., for the fair. He also visited Birney, where a photograph of him was taken at the front gate to the Cox house. Living in the Cox house at the time were Leonard and Mary Gordon Collins Kruidenier. It was most likely at this juncture that Mary Gordon discovered the artist, Bill Gollings. A cordial friendship evolved between Bill Gollings and Mary Gordon Collins Kruidenier, which was evident by several gifts to her from the artist.

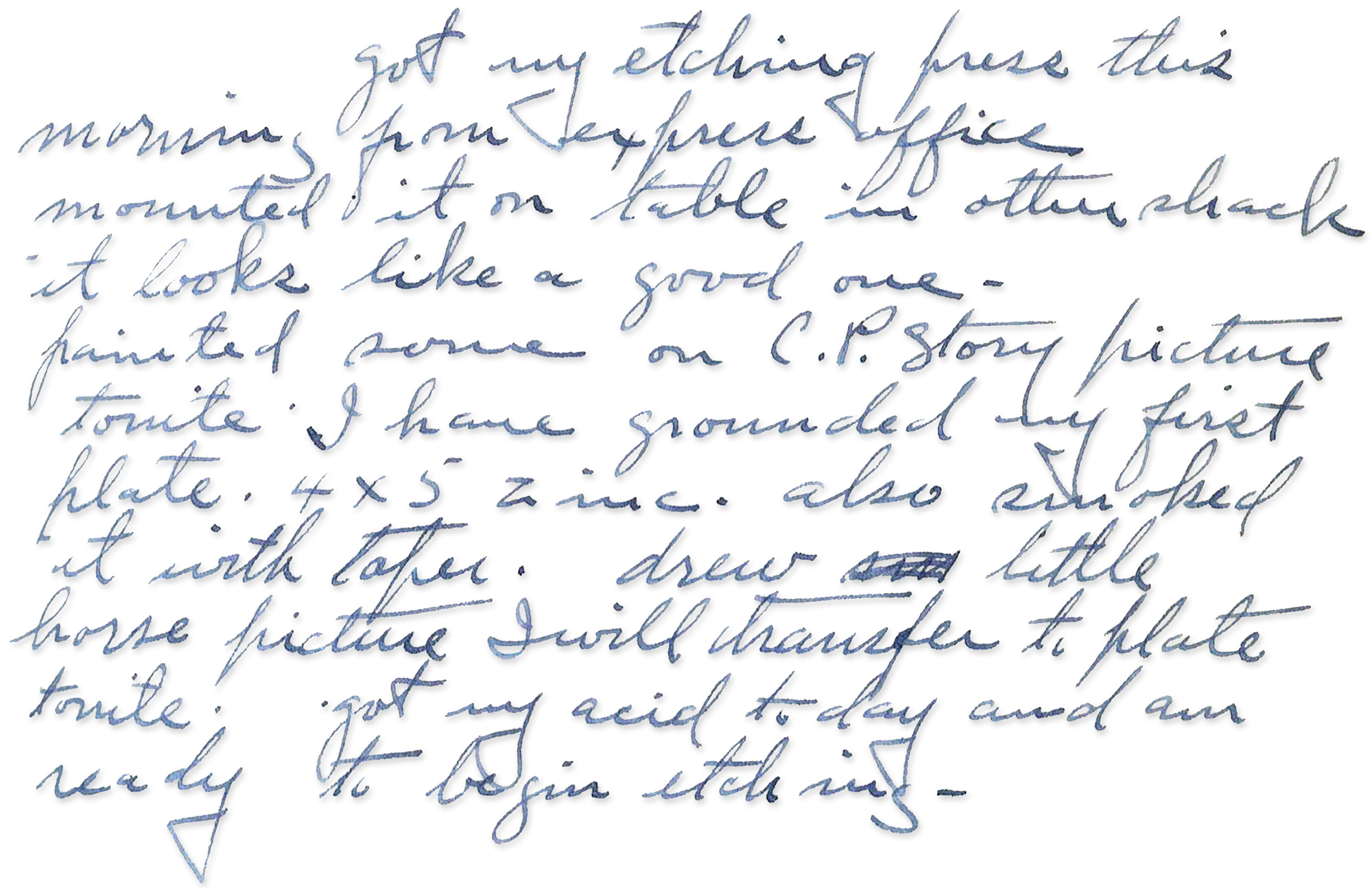

Around this time, at Kleiber’s urging, Gollings began to explore printmaking. Until then, he had worked primarily in oil. He wrote about the process in his diary.

May 17, 1926

“Got my etching press this morning from express office mounted it on table in other shack it looks like a good one. Painted some on C. P. Story picture tonite. I have grounded my first plate 4 x 5 zinc. Also smoked it with tapes. Drew little horse picture I will transfer to plate tonite. Got my acid today and am ready to begin etching.”

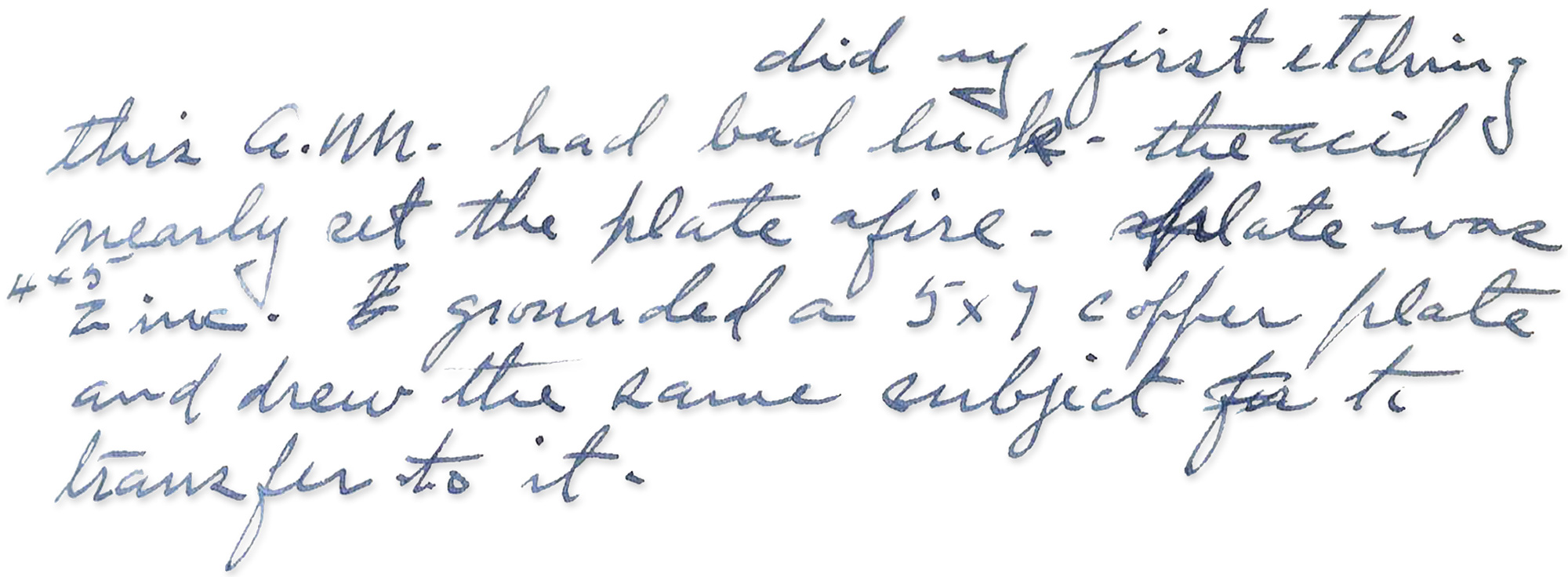

His writings reveal how the difficulty of etching became apparent to the artist.

May 19, 1926

“Did my first etching this a.m. had bad luck – the acid nearly set the plate afire. Plate was 4 x 5 zinc. Grounded a 5 x 7 copper plate and drew the same subject for to transfer to it.”

May 26, 1926

“Etched my first copper plate. Came out fair room for improvement. Made 4 prints this afternoon. Have learned several things about etching and printing. Had better luck on copper than I did with zinc.”

From 1926 to his death on April 17, 1932, Bill Gollings completed approximately 36 designs including one block or linoleum print design. Hans Kleiber outlived his friend by 35 years. His career included the printing of more than 440 designs.

Mary Gordon Collins Kruidenier and Leonard Kruidenier separated and later divorced, after having one child together. Sadly, three weeks after her daughter’s graduation in 1938, Mary Gordon passed away. Leonard returned to Iowa but maintained business dealings in Montana.

My brief exposure to the vanishing West was accomplished through the writings and photos of these four individuals. Through the personal diaries of Bill Gollings, letters home from Leonard Kruidenier, and the photographic mementoes of Mary Gordon Collins Kruidenier, the stories of these four people in this remarkable time come full circle.

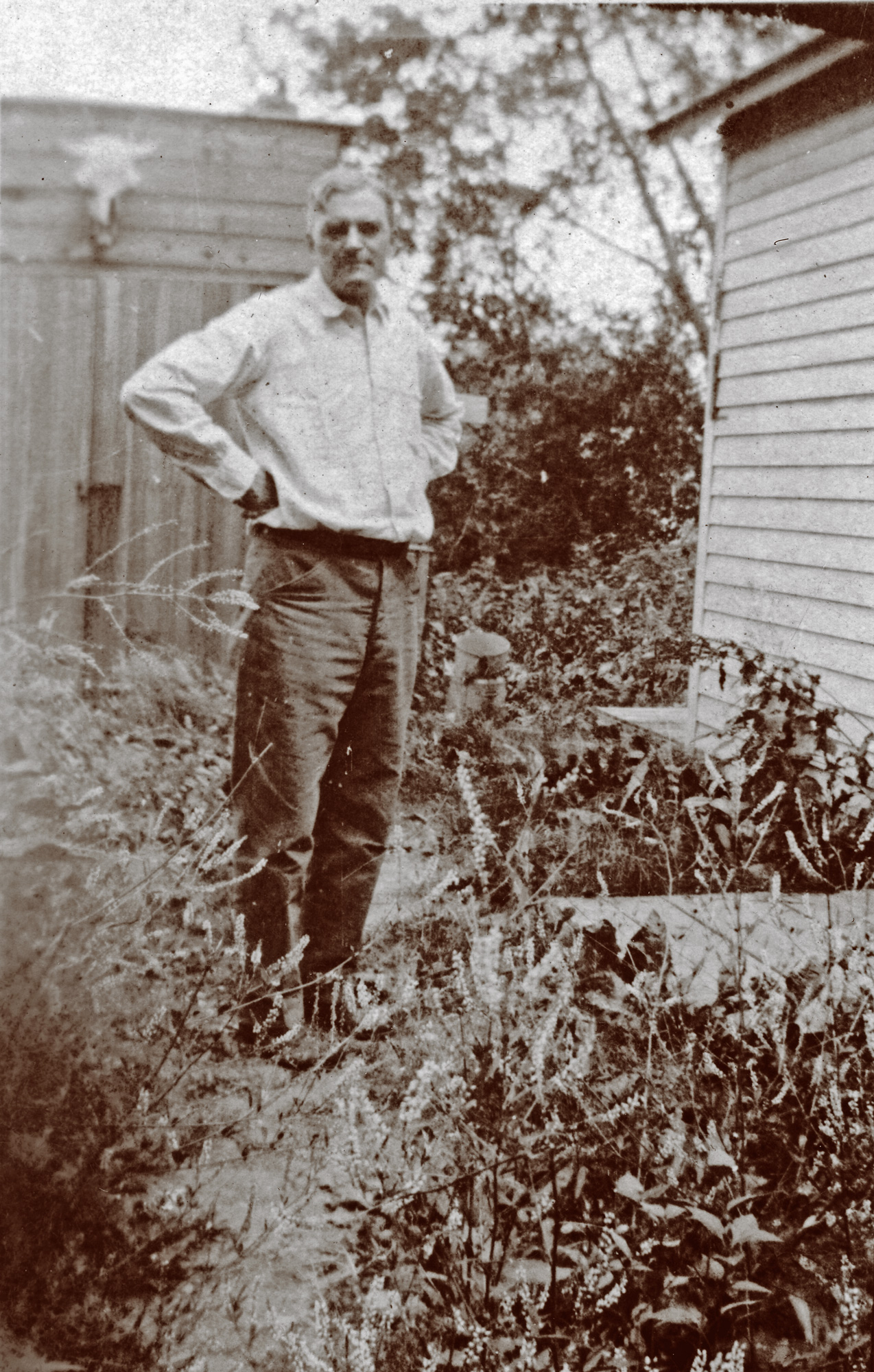

- Photograph of Gollings attributed to being taken by Mary Gordon Collins Kruidenier in the summer of 1926 at his home. Photo courtesy of Meadowlark Gallery

- Busting a Steer | etching | 8.75″ X 12.75″ Image courtesy of Meadowlark Gallery

- From left to right: Will James, Mary Gordon Collins Kruidenier, Leonard Kruidenier, and Hans Kleiber. Will James was photographed at the front gate to the Cox house in Birney, Mont. in approximately September, 1925. Mary Gordon Collins Kruidenier was

- High and Wild | etching | 6.75″ X 4.875″ Image courtesy of Meadowlark Gallery

- Mary Gordon Collins Kruidenier’s hat with brands from ranches around the area. The OW was the Kendrick ranch at the head of Hanging Woman Creek southeast of Birney, Mont. The COL brand was owned by Natalie Brown Woodward.

- Detail page view of October 15 and 16, 1926 from the personal diary of Gollings. Also shown are the seven years of Gollings daily planners. Photo Courtesy of Meadowlark Gallery

No Comments