23 Jul Western Design: In the Studio with Wendy Marquis, Christopher Paolini and Amber Jean

The Painters Road: Wendy Marquis

Written and Photographed by Jennifer Olsson

The air is heavy with the scent of freshly cut hay as we rattle along a rolling country road near Manhattan, Montana. Wendy Marquis shifts the gears of her handsomely restored 1960 buttercup-yellow Ford pick-up, and searches for a view, an angle, or an abandoned outbuilding, like someone looking up a new address. She slows. The sun has begun to drop. Shadows stretch and the edges of the world seem to soften.

“Not here,” she says, “but when we turn around you can see the barn I like.”

She cranks the truck to the left, makes a U-turn, and eases it carefully to the side of the road. We climb to the back and stand in the truck bed. Through the branches of a cottonwood that has resided along a narrow creek for what must be nearly 50 years, Wendy points toward the favored red-iconic structure holding court on the hillside; its weather vane winks in the afternoon light.

Wendy snaps photos to remind her to return to this place, and to capture the light that inspires her art to tell its story. In the field across the road, a bachelor party of bulls casually grazes. She decides to set up her easel, but better angles might be had by moving inside the posted fence. We pause. To hop the barbed wire or not? We wisely decide — not a good idea; an errant charge might make a mess of the paints. Suddenly, a Carhartt-clad gentleman four-wheels up the road in our direction. We have a feeling he heard our thoughts.

The rancher, Todd Flikkema, arrives on his mechanical steed and kills the engine. “You’re not thinkin’ of crossing that field are you?” He asks smiling at what might have been our folly. “No sir!” we respond in unison.

Wendy’s eyes shine along with her charm as she assures him she is not a cattle rustler but an artist who only wants to capture his livestock on canvas. He is intrigued, and hospitable, and invites us onto his property. Wendy makes another fast friend and is welcomed into a new space of weathered outbuildings, retired farm equipment and barn wood. She’ll take the magnificence of the landscape back to her studio and give it another life on canvas.

Wendy (Miller) Marquis grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, surrounded by art and artists. Her mother, Arline, owned Gallery Vendome in downtown Pittsburgh, and her childhood home was filled with art including signed serigraphs and lithographs by Miró, Picasso and Dali. Family friend Marcel Marceau, the famous mime and also an accomplished painter, was often a dinner guest. Wendy’s father, Charles, was a prosthodontist who assisted the make-up department in the creation of decayed teeth for the leads in the Oscar-winning film, Amadeus.

“Pretty much everyone has artistic talent in my family. My twin brother is naturally artistic and my sister, Sandi, designs jewelry in New York City. My mom painted and had the gallery; even my dentist dad was artistic. I used to watch him work on ways to correct people’s teeth so they could smile again. He was a kind of sculptor,” she says with a grin.

Wendy attended The School of The Museum of Fine Arts Boston, before graduating with degrees in graphic design and studio art from the University of Arizona. After college she worked for a design studio in Boston, then married, moved to New Hampshire and started her own design business. That’s when she also began faux finishing and painting murals. The Inn at Church Landing in Meredith, New Hampshire, discovered Wendy’s talent and soon their walls became her canvas as well as their headboards, breakfast bars, chair backs, cabinetry, floor cloths and paneled cupboards.

In 2006 Wendy moved from New Hampshire to Montana with her husband and two-teenage daughters when her husband’s job brought them west. She continued painting murals, and several of her works can be seen around Bozeman, but there came a day when she felt compelled to begin painting her new-found home.

Landscapes are a favorite subject, and she masterfully captures the essence of clouds and sky even though early on she thought her mind was playing tricks on her.

“Since arriving in Montana my work has gotten brighter and crisper; it’s because of the light. At first I felt my skies were way too blue, but then I went outside to check, and sure enough, the sky really was that blue.”

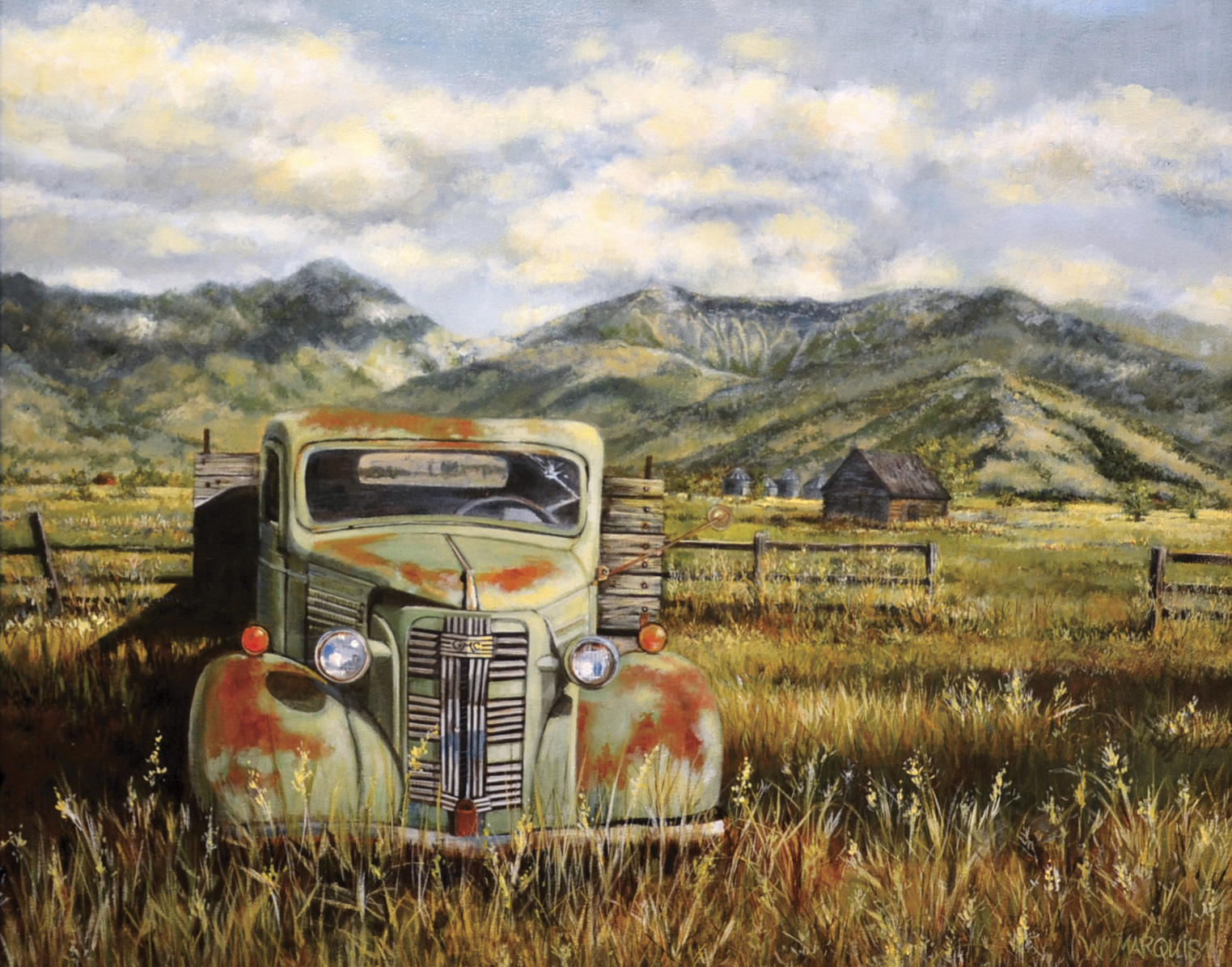

And one day, while scouting for subject matter, a rusted ’37 GMC truck sunk in the ground with the Bridger Mountains in the distance called her name.

“Everything about that scene was right; the light, the shadow, the colors. Bridger GMC won an annual cover contest for American Artist’s Watercolor Magazine. After that I became more aware of the abandoned trucks, the grain bins, the manmade structures that have redefined what was once a wilderness. I saw those metallic monuments as telling a story about the land and the people who were here, and who are still here.”

A series of truck paintings followed. She discovered them in junkyards, behind buildings or often just sitting and rusting where they quit, generations of field mice living in the front seat. She painted them as she found them, or when hay bales or a field needed company, she painted them into scenes to please the composition. Soon, a new group of fans became interested in Wendy’s art.

Later in the day we return to her working studio and gallery in downtown Belgrade. The walls are lined with landscapes, winding roads, barns, trucks, clouds and sky you swear came in the door behind you. In several pieces, grain silos achieve their status as the high rises of the plains, and her painterly method gives them both clarity and softness — like a faded memory. But a desire to paint on larger surfaces is returning.

“I want to enlarge what I do. It feels like that might be my next move; to give big spaces a big place to live on the canvas.”

Wendy’s art teaches you to see more than you did before. She will, show you the backward look through tree limbs, put you on the road that winds surreptitiously to the top of a hill, park you next to an aged pick-up, and walk you across a wheat field. You can hear her muse calling you to rediscover the Montana landscape: Look — it’s there, right where it has always been, right now in front of you.

Jennifer Olsson, the great-granddaughter of early Montana settlers, has called Montana home since 1981. She writes for numerous publications and is the author of Fly Fishing the River of Second Chances; Life, Love, and a River in Sweden, and Cast Again; Tales of a Fly-Fishing Guide.

A Writer’s Roost: Christopher Paolini

Written by Seabring Davis

Photographed by Lynn Donaldson

From his hilltop home studio in Montana’s Paradise Valley, writer Christopher Paolini looks over the Absaroka Mountains. There, along the spiny ridges and between gauged peaks was where he drew the inspiration for his fantasy novel, Eragon, which eventually grew into the worldwide best-selling series entitled The Inheritance Cycle, a coming of age saga about a young boy who discovers a dragon egg and the weight of his destiny tied to its power.

The landscape is a constant source of inspiration, he says. It was a launching point for the dramatic world of Alagaesia, where dragons fly, magic lingers and good versus evil is a swinging pendulum. Yet, it’s in this simple office where the real work gets done, where Paolini’s imagination fills in the crevasses that the mountains offer. It’s in this room, at the highest point of the family home he shares with his parents and sister Angela, where the characters’ lives change forever.

“This is the lair,” says Paolini, with a wry smile. He is tall and slim, dressed in a cotton shirt and jeans, dark-haired and bespectacled. He thinks before he speaks, careful with his responses, but is quick to smile. The journey from self-published teen novelist to an internationally acclaimed author is a coming of age story by itself.

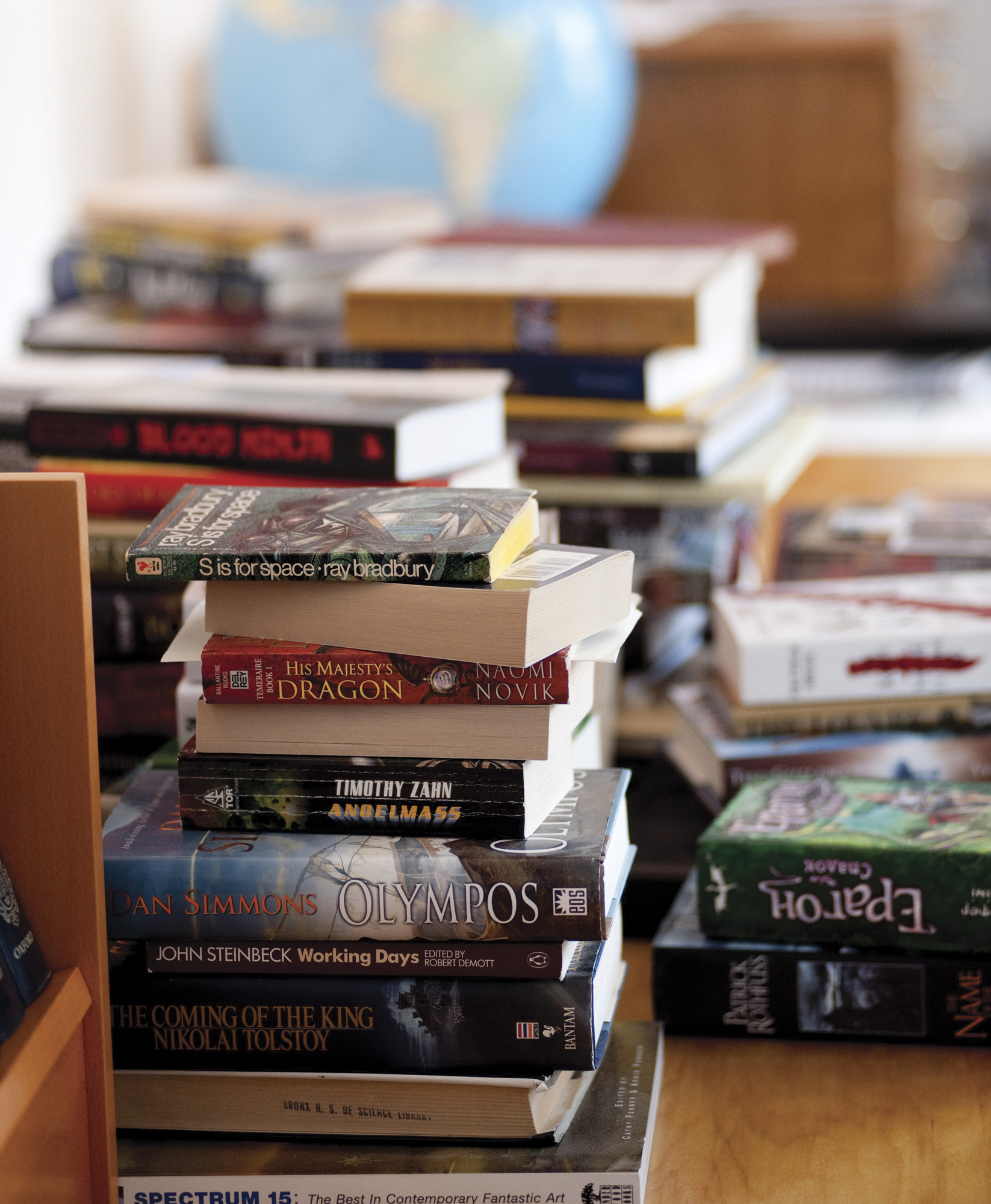

The room is open and simply furnished with a seating area that centers on the picture window and the valley view. A carved wooden dragon clock hangs prominently on the wall. His desk and computer are tucked in the corner, neatly surrounded by what he considers essential research books of ancient languages, 20,000 Baby Names, dictionaries and a thesaurus. Behind his desk, the walls are stacked with books he has read, both literary favorites and go-to reference guides to aid in his writing. He keeps files of images nearby that inspire “the world” that he has crafted in his novels, a place that may be fictional, but to be believable has truly taken on a life of its own.

On the opposite side of the office are stacks of books he plans to read, titles that range between the classics of Alexander Pushkin to John Steinbeck to contemporary works from Dan Brown to C.E. Thornton. A long row of wide, shallow drawers store Paolini’s artwork. Before he found his stride in writing, he dreamed of being a professional artist. In fact, many of the characters in his books, from Saphira the dragon to young Eragon, begin with a drawing.

Although his books have been translated into 49 languages in 54 countries and their success has taken the author on extensive multi-month tours of North America, Europe and Asia, Paolini remains grateful for his home in Montana.

“Coming home for me is a way to rest and recover and to be who I am,” he says, “When I’m home it’s just Christopher.”

Humble, yet generous with his time at home, Paolini has been a dedicated supporter of the local Park County Library in Livingston and has made frequent appearances in rural schools. A natural storyteller, he can hold the attention of a room full of sixth-, seventh- and eighth-graders like few adults can.

“I very much remember being that age and the insecurity I felt when I was first starting out,” Paolini notes.

Paolini was home-schooled by his parents and as a creative exercise his mother suggested he write his own book. He wrote the first draft of Eragon at 15, taking another year to revise the draft, then a third year preparing it for publication, which entailed typesetting the manuscript, copy editing, proofreading and creating the cover design, which Christopher drew himself. It was finally self-published in 2001. The Paolini family dedicated much of 2002 and 2003 to promoting the book at libraries and bookstores locally.

In the summer of 2002 author Carl Hiaasen, while on vacation in Montana, noticed his stepson reading a copy of Eragon with such enthusiasm, that he decided to pass it along to his own publisher. What happened next is the stuff of aspiring-writer fantasy. The prestigious publishing company of Alfred A. Knopf Books For Young Readers (an imprint of Random House Children’s Books) contacted Christopher and after a final round of arduous editing, Knopf published Eragon in 2003.

By 2012, Paolini’s fourth and final book in the series Inheritance was published and received with highly anticipated acclaim. With it the story of the character Eragon is complete. But Paolini’s real-life journey continues. The author is exploring other ideas for books. He takes college courses online and spends more time hiking in the surrounding mountains, which sparked his creative passion from the beginning.

In the last decade, though Paolini has obviously matured and embraced his success, he remains grounded in family, in his creative work and most of all at home in Montana.

Seabring Davis is Big Sky Journal’s editor in chief.

Sculpting a Creative Life: Amber Jean

Written by Christine Rogel

On a mountainside overlooking the valley where the beautiful town of Livingston, Montana, sits quietly against the banks of the Yellowstone River, a dirt road winds and eventually ends at Amber Jean’s dream studio.

It’s a large building, open and sunlit, complete with a hoist system to help maneuver her large sculptures and a loft for napping. She’s working on a reliquary series inspired by a saint’s knucklebone she saw at age 17 in a German cathedral and the feeling of sacredness. Sawdust covers the ground below a nearly 12-foot tree, split lengthwise, its halves laid side-by-side like a patient in a prolonged operation. Its organs are painfully chiseled to life, fleck by fleck.

Amber Jean Reinhard (she uses a shortened name professionally) is a multimedia artist creating works that are influenced by the natural world and her personal history. Over the years, she’s built a creative portfolio that even includes sculpting thousands of pounds of chocolate for Nestle. She writes, is a public speaker, paints murals, creates monoprints and bronze sculptures; but she’ll quickly admit that wood is her primary passion.

In her work, she mixes wood types to achieve tonal and grain variations, and sometimes carves and stains the wood until it looks like hammered metal. From gun cabinets with detailed images of grizzlies and mountains lions carved in solid walnut, to a grandfather clock with haunting wolves, to mirrors, doors and carved cigar boxes, Amber turns wood into works with unique detail. Some of her bronze pieces are even initially carved from wood, such as Sojourn a lifelike buffalo sculpture that doubles as a bench and will be on display at the Bozeman-Yellowstone International Airport.

“I just threw myself into it and learned [carving] on my own mostly, and it really started because wood was plentiful in the beginning,” she said. “It was one of those relationships where it just grew. I love the smell of wood. I love the wood grain. I love how much it lives decades after its dead. It’s so compelling.”

Amber’s creative process is grounded in her active life. She’s been shipwrecked on a Mexican island, stepped on by a bear while sleeping alone in the backcountry, nearly blown off Mount Rainer and flipped in class-V rapids. She worked seasonally as a backcountry ranger and firefighter in college. On her days off, she still goes ice climbing.

“For me, the strongest spiritual moments I feel are often outdoors … and I wanted to bring that back into my work,” she said, explaining that a night spent under the stars in the Pryor Mountains and a wild mustang encounter led her to creating Spirits Untamed, a large, gnarled juniper and mahogany bed built by Don Butts and carefully carved by Amber. Wild mustangs, vivid and lively, impressively charge across the head and footboard. The bed sold for $38,000 and won the People’s Choice and Best Western Spirit awards during the 1999 Western Design Conference.

Drawing upon experience, she takes her life’s stories and pairs them down to the elements, like a poem or haiku, pulling the few lines with impact and transforming them into art. She spends time on each detail until the animals she sculpts become lifelike characters in the plot. Finally “giving birth” to her work and handing it to her audience, it develops a new life and story based on their experience, she explains.

By continuing to seek adventures and possibilities, Amber Jean will also continue to sculpt a creative life, sharing moments along the way for others to enjoy.

Christine Rogel is a contributing editor for Western Art & Architecture and for Big Sky Journal.

No Comments