16 Feb Books: Reading the West

The state of fly fishing in Yellowstone National Park, and indeed the state of fly fishing in America, is the subject of Greg French’s The Imperiled Cutthroat: Tracing the Fate of Yellowstone’s Native Trout (Patagonia, $24.95). French is a well-known Australian fishing writer, and his outsider’s perspective and deeply held opinions are what propel this book out of its genre (perhaps best generically described as fly-fishing memoir) and onto a shelf beside works of important environmental and cultural criticism.

In 2012, French and his wife flew from Tasmania to Bozeman, Montana, with big plans for exploring Yellowstone’s fisheries and backcountry. Underlying the travelogue of their trip up Paradise Valley to the park, their passage under the iconic Roosevelt Arch, and their encounters with fishing guides and locals along the way, is both a palpable sense of urgency and a poignant nostalgia for fishing and trout as they used to be. American coffee and American park policy are both seen through comparisons to their Australian counterparts; coffee suffers, and the jury is still out on the parks when he recounts his tale of obtaining a backcountry permit. But the magic and wonder of Yellowstone — and the threats to its native fish — come alive through vividly painted scenes and encounters with fellow travelers. French has little interest in geology. His obsession is the fish: where to catch them, how to catch them, and what has happened to them throughout history.

French’s stated purpose behind the trip is not just living out a lifelong dream, it is also his goal to raise awareness of fisheries issues (nonnative species, climate change, overfishing) before it’s too late. He expresses a near panic at the thought of not having this experience, even moving up their travel plans a full year, stating, “Right now I am filled with an urgency of the sort one feels when racing home to see an aging parent after a sudden illness.” He offers an excellent natural history of the native cutthroat trout and explores the threats to it with an open mind. He is perhaps less open minded on the “persecution” of bison, but his indignation on their behalf is both reasonable and thought provoking. And he is always, seemingly, willing to ask, “What if we’re wrong? What if I’m wrong?”

Ultimately, this beautiful volume inspires, teaches, and entertains, with vivid and evocative color illustrations peppered throughout the book. French’s take on Yellowstone and its fish is opinionated, funny, and mixed between despair and fervent hope. For American readers — and especially regular visitors to the Yellowstone region — his particular biases and life experiences will challenge assumptions.

Losing Eden: An Environmental History of the American West by Sara Dant, a professor of history at Weber State University (Wiley, $29.95), asks critical questions about whether the West has ever been an Eden, and explores the ways human contact, politics, and wars have shaped the environmental history of the West without presuming that there is an ideal state to which we should return. Taking the long view — from the migration of Beringia, to the Columbian influence on the West, to the policies and politics of the 20th century — Dant considers both how the natural landscape and natural resources found in the American West shaped its history, and how human history altered nature.

Dant’s particular focus in the study of history is environmental politics in the U.S., and this volume reflects her time considering the interaction of commerce, politics, and human nature. Fascinating details about geographical extremes, weather, and wildlife are the architecture on which her narrative is given shape and life and credibility. Some realities are part of the common sensibility — the 10 driest states can all be found in the American West. Others challenge assumptions about the rural nature of the region — California, Arizona, Nevada, and Utah are all among the top 10 most urban states by percentage of population living in urban areas.

While Dant doesn’t argue that there is a pristine natural state that we should idealize in the West, she does point out some rather alarming trends that have emerged as part of the shoulder-to-shoulder interactions of competing and complementary interests. The rapid, documented rise of annual average temperatures in the Rocky Mountain states correlates to ongoing and increasingly devastating drought conditions. At minimum, wildfires, pine beetle infestations, and the death of giant sequoias in California all reflect an unprecedented degree of change in environmental conditions.

Taking the long view, Dant illustrates how the West and its natural resources have always been central to national debates about the relationship between innovation, extraction, economics, politics, and the environment. Her lucid prose and evidentiary approach to these discussions make this book, if not a handbook for behavior, a treatise on how to better understand it. Filled with maps, graphs, and useful illustrations, this excellent book reveals much about our evolution over time and offers new perspectives on how we got to where we are today.

Water is for Fighting Over and Other Myths about Water in the West by John Fleck (Island Press, $30) is a surprisingly optimistic book. Opening with a scene on the Colorado River in San Luis, Sonora, Mexico, where the author witnesses a dry riverbed come to life with water released from the north, he praises a scene filled with delighted children and international cooperation. From that ebullient introduction, he considers the seminal work on water shortages and water policy in the West, Cadillac Desert, and asks why Marc Reisner’s expectation of catastrophe has not been fulfilled. Fleck points out, “despite what Reisner had taught me, people’s faucets were still running. Their farms were not drying up. No city was left abandoned.”

Then Fleck asks an interesting series of questions: “When the water runs short, who actually runs out? What does that look like?” Fleck’s argument is that the answers to those questions don’t negate the catastrophe narrative nor lessen the burden that mismanagement of water has left, but they do support an alternative perspective on whether water really is for fighting over. He posits that if everyone ignores their own adaptive capacity and simply fights for more, or even fights for the share they’ve got now in a shrinking system, we are led headlong into conflict with dangerous results. If instead we recognize our ability to make do with less, and invest in institutions that facilitate water sharing, we can create systems for robust, flexible, and equitable water allocation.

The point that Fleck makes is a valuable one. He doesn’t argue that there is no water crisis. He simply suggests that just shouting about a crisis doesn’t empower individuals, communities, governments, or corporations to collaborate to find solutions. By turning on its head the notion that water is something for fighting over, and pointing out the many ways in which international, bipartisan, and even public-private cooperation has already taken place in the face of potential water shortages, he makes the reader think differently not just about this crisis but about public policy, the media, and the risk of entrenchment in old thinking. A thought-provoking book.

OF NOTE

A young-looking Brad Pitt looks out from under a shock of blond bangs and handles a fishing boat on the cover of Shot in Montana: A History of Big Sky Cinema by Brian D’Ambrosio (Riverbend, $22.95). Pitt’s indelible performance in that most iconic of Montana movies, “A River Runs Through It,” is just one of the celebrated moments in Montana’s century-long cinematic history featured in this collectible volume of behind-the-scenes stories and photos. The book features more than 90 films starring the Treasure State, from “Rancho Deluxe” to “The Horse Whisperer” to cameo appearances in “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.” Movie buffs will love the trivia, the more than 100 photos, and the trip down a collective memory lane that recalling these films and their stars will inspire.

Jon Axline’s latest book to feature the roads and byways of Montana is The Beartooth Highway: A History of America’s Most Beautiful Drive (History Press, $21.99). Once again, Axline digs into the archives and personal accounts from Montana’s transportation history and brings to life the grit and determination behind a massive infrastructure project. Axline’s particular interest in and experience with Montana’s transportation history (he is the author of Taming Big Sky Country: The History of Montana Transportation from Trails to Interstates) allows him to put the Beartooth Highway in context. He also marvels at the grandeur of both the effort to carve the road into Yellowstone Park and the views from its heights. Filled with black-and-white archival images and color photographs, this is a great addition to the literature on what Charles Kuralt called “America’s Most Beautiful Drive.”

Yankees & Rebels on the Upper Missouri: Steamboats, Gold and Peace by Ken Robison (History Press, $21.99) offers a vivid portrait of the 30-year period of time, starting in the 1860s at the height of the Civil War, when the Missouri River served as both a natural and bustling highway for men and women of all stripes making their way into the Pacific Northwest. The colorful characters, from outlaws to lawmen, and the dramatic events brought about by their collision in the Upper Missouri River region make for fascinating reading. Robison’s episodic approach, along with the archival images and extensive source material, gives the time period snap and color. The breadth of his subject matter, from the James-Younger Gang to the affairs of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, reveals a region that was far from an empty frontier in the late 19th century.

The Art of Yellowstone Science: Mammoth Hot Springs as a Window on the Universe by Bruce W. Fouke and Tom Murphy (Crystal Creek Press, $50) features stunning images of the travertine terraces found in northern Yellowstone National Park. And it also offers fascinating sciences lessons and a suggestion to look at the world and its ecosystems and natural processes with an understanding that beauty — or art — and science go hand in hand. It’s a book about looking closely at something and allowing that something to astonish you and pique your curiosity.

The haunting image of a female lion staring out from the cover of Wild Encounters: Iconic Photographs of the World’s Vanishing Animals and Cultures (Rizzoli, $75) conveys the immediacy of this volume of 160 photographs of the most vulnerable species and cultures around the world. Renowned wildlife photographer David Yarrow offers stunning and intimate images of elephants, lions, tigers, and bears in their native habitats across six continents, pulled from his two decades of experience in the field. This book clearly is driven by the author’s passion for conservation and highlights the real risks to the continued survival of these animals and their place on the planet. Beautiful and inspirational, this is a great gift book and a reminder of the wonder that can still be found in the world.

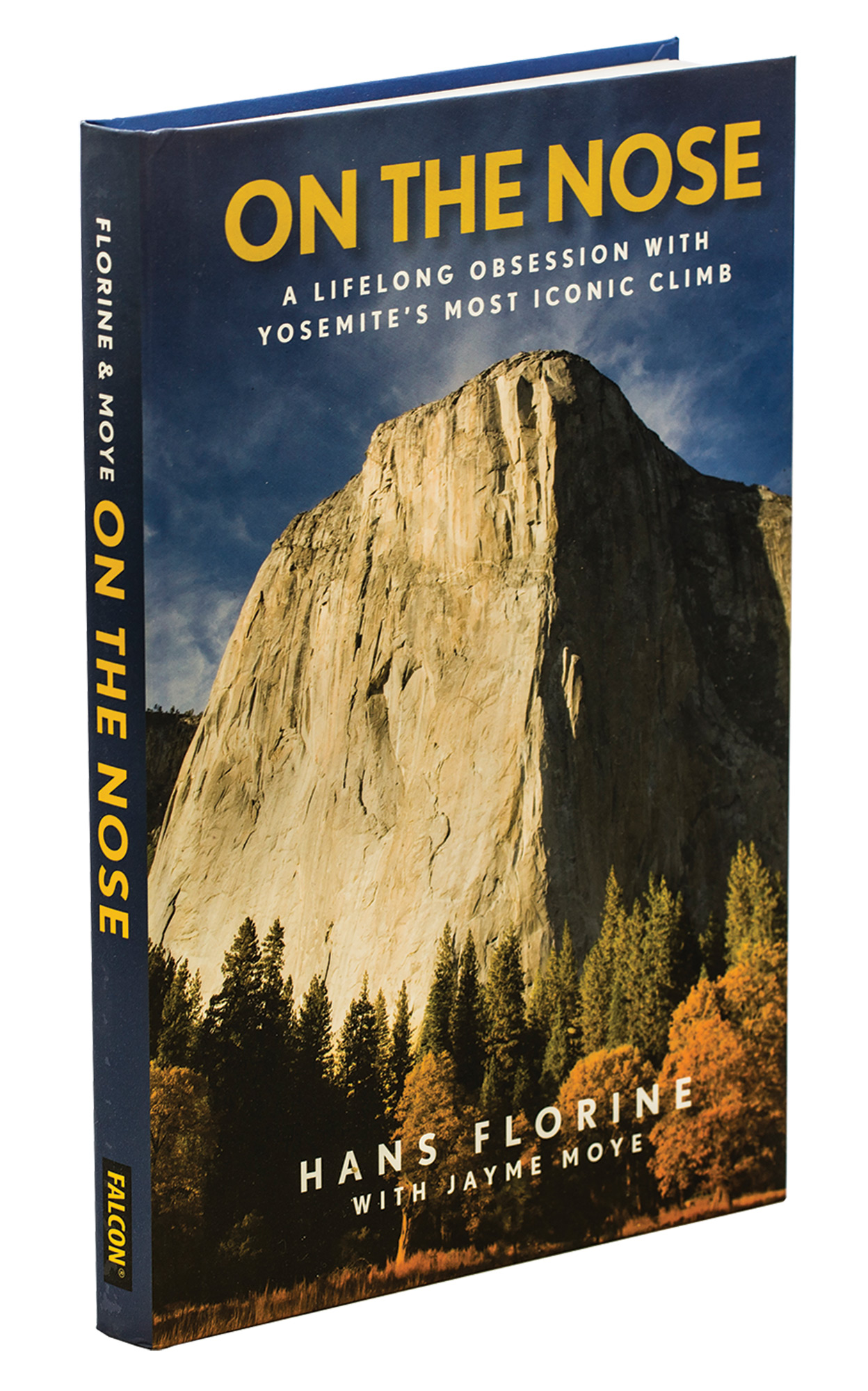

In On the Nose: A Lifelong Obsession with Yosemite’s Most Iconic Climb (Falcon Guides, $25) big-wall climbing legend Hans Florine tackles the big questions, starting with why anyone would want to climb the 3,000-foot granite cliff face of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park more than a hundred times. The Nose, the route Florine holds the speed record for climbing, is one of the most famous rock-climbing routes on the planet. Where most climbers take between 12 to 96 hours to follow the route, Florine’s persistence and drive has helped him whittle his time down to two and a half hours. The tales of his many adventures, failures, and successes during his career on the rocks make for great adventure reading, and contain lessons in how to live a rich and satisfying life and turn goals into reality.

No Comments