12 Aug Paper Talking

Charles M. Russell was not the only artist who illustrated his letters to friends, but he had a special gift. Writing, as he readily admitted, was work for him, but he found his own inimitable voice by thinking of his letters as “paper talk;” not school exercises in correct grammar and spelling but conversations with people he knew, spiced with humor, sentiment, and a keen appreciation for human nature. He illustrated his prose with drawings, usually in pen and ink, and watercolor. Some of the sketches were miniature versions of his major subjects — old-time Indians, cowboys, and wildlife; others were cartoons starring Russell himself as a Western relic dressed in cowboy boots, Stetson, and his signature Métis sash, wryly observing the bustling, modern world as it passed by.

Russell was, after all, legitimately a cowboy, having followed his boyhood yearnings westward in 1880 when, as an impressionable 16-year-old, he left St. Louis and the comforts of a prosperous family life for a summer in Montana. It proved, for him, to be an endless summer; he still called Montana home when he died in Great Falls in 1926. From 1882 till 1893 he made his living as a wrangler, “singing to the horses and cattle” on roundups in the Judith Basin and north of the Milk River, and sowing his share of wild oats until he settled down to his art — a natural gift. In 1896, he ended his wandering days by marrying a pretty 18-year-old named Nancy “Mame” Cooper. They settled in Great Falls the next year and, with Nancy managing the business end of things, Russell flourished as the prototypical “cowboy artist,” his knowledge of Western life honed by his years in the saddle and his artistry refined by exposure to other artists and, through them, to the fundamentals of his craft.

Courtesy of Nygard/Mongerson/Tierney Galleries

Russell had occasion to write to his family in St. Louis when he was still an itinerant cowboy, and began supplementing words with drawings, though none of his letters survived that were dated before 1887. But that year his tiny watercolor Waiting for a Chinook — showing an emaciated cow and circling wolves in drifting snow — was greeted with wide acclaim. From then on, recipients began keeping what he sent, alert to their potential value. Smaller than a postcard, Waiting for a Chinook compressed the tragic consequences of the bitter winter of 1886-87 into a powerful image with a stark message: The open range cattle industry was doomed.

“The whole scene was one of bleakness and starvation and portrayed that which the pen could not describe as vividly,” recalled Charles Schatzlein, a Butte hardware merchant who was Russell’s first art dealer. Thereafter, Nancy said, recipients prized Russell’s letters. “Either having been stolen or burned is the only thing that has taken Charlie’s letters from the people to whom they were written.” It was a pardonable exaggeration, but a high percentage of his letters do survive, most from the 20th century when local recognition transitioned into national and even international renown.

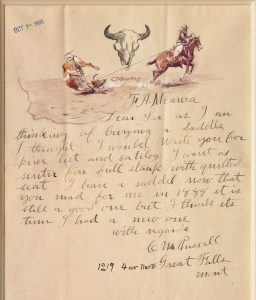

Russell penned few business letters as such — that was Nancy’s department — but when he did they could be as delightful as his request in 1905 for a catalog and price list from the Cheyenne, Wyoming, saddle maker F. A. Meanea. “I want a senter fire full stamp with quilted seat,” Russell explained beneath a drawing of a cowboy roping a steer, noting that Meanea built the saddle he had used since 1888. It was still good, he wrote, “but I think its time I had a new one.” He sounded like a little boy drawing up his Christmas wish list for Santa. By 1905, he deserved to indulge himself a little. He had already made a splash in New York — “Smart Set Lionizing a Cowboy Artist,” one headline read — and had secured his reputation as a presence on the art scene enjoying the kind of success of which other artists only dreamed. Illustration commissions, postcard and calendar reproductions, color prints, magazine appearances, and — beginning in St. Louis in 1903 — one-man exhibitions made him famous, and fame brought obligations.

Accepting or declining a steady stream of invitations and requests, and offering thanks for favors received, required a Russell response — usually illustrated. He made the task of writing references and replies to those soliciting artistic advice — mounting burdens with his mounting fame — an art form that gave free rein to his knack for original phrasing and creative spelling. In a letter addressed to Harry Carey, William S. Hart, Tom Mix, Douglas Fairbanks, Neal Hart, and Will Rogers, “ore aney other moovey man that wants r[i]ders,” he recommended Fred Warrington, a cowboy he knew. “Put a horse under Warrington,” he wrote. “This will be a faver to me a kindness to the horse a job for Warrington and a horse man to him that hires him Good luck to whoever it is.” And in a letter to Will James, himself on the cusp of fame as a writer and illustrator, he advised, “you say you havent used color much dont be afraid of paint I think its easier than eather pen ore pensol … use paint but dont get smeary let sombody elce do that keep on making real men horses and cows of corse the real artistick may never know you but nature loving regular men will and thair is more of the last kind in this old world.”

Bob Benn of Kalispell, Montana, earned the moniker from Russell “Bob the Booster,” given his advocacy for the Flathead Valley. Petrie Collection, photograph courtesy of Jeff Wells, Denver Art Museum

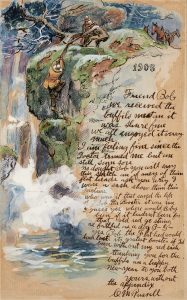

Many Russell letters had a practical function, and were directed to new acquaintances that he made on his travels. But most were addressed to old friends. Russell’s “Great Falls bunch” — brother Elks, cigar store owners, picture framers, and saloon proprietors like Albert J. Trigg of the Brunswick, Bill Rance of the Silver Dollar, and Sid Willis of The Mint — were regular letter recipients who could be counted on to circulate them for the enjoyment of their clientele. Friends across Montana got unexpected letters to be coveted and shared. Perhaps they were sick and needed to be jollied up. Perhaps they had given him some venison or buffalo meat for his dinner table. Or perhaps they were just on his mind. Bob Benn of Kalispell (“Bob the Booster,” Russell called him, because he was forever promoting the Flathead Valley) received a half-dozen letters from the artist, none more delightful than a 1908 New Year’s greeting showing Russell and the New York illustrator Phil Goodwin rescuing “Bob the Booster” by using Russell’s sash as a rope to haul him out of harm’s way. Both had been guests at the Russells’ Bull Head Lodge on Lake McDonald the previous summer, where the incident (whatever its specifics) occurred, providing fodder for the kind of “foolishness” Russell conjured up to amuse his friends.

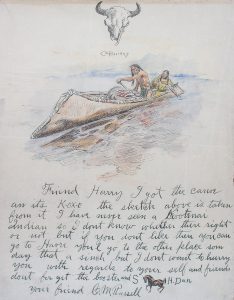

Because of the nature of his art, getting things right was important to him: the harnessing of a dog-sled team, the brands on horses, the shape of a Kootenai canoe. He often tapped a Kalispell taxidermist, Harry Stanford, for historical information and the details of animal anatomy. His query about a Kootenai canoe resulted in the gift of a model from Stanford that he added to his studio collection. These objects constituted a research library for the artist. His thank you to Stanford reminds us that paper talk was conversation. Whenever he was in Kalispell, he visited Stanford’s shop, and talk flowed. Stanford once mentioned that a mutual acquaintance had found religion. Russell responded, “At his age and with his record I’d take out fire insurance too.” Similarly, paper talk allowed for bantering exchanges. In his thank-you note for the canoe model, Russell added that if Stanford didn’t like the accompanying sketch, he “could go to Havre—youl go to the other place som day that[‘s] a sinch but I dont want to hurry you.”

Paper talk was exactly that. Will Crawford, a professional New York illustrator who specialized in meticulous pen and ink drawings, liked writing letters about as much as Russell did, and in their infrequent exchanges each claimed the title “Champion Bum Letter Writer.”

Bob Stuart, who rode with Russell for his Uncle Granville’s DHS brand in the early 1880s, sent Russell a postcard of a bright red lobster above the message, “Why dont you write?”

“I received your long letter where you called me a lobster,” Russell shot back, then made amends for his silence with three pages about a recent trip to a Mexican ranch and the vaqueros who had caught his artist’s eye. He used to think the cowpunchers of their youth “were pritty fancy,” he told Stuart, “but for pritty these mexicons make them look like hay diggers.” Mexico was “all open range … an old time cow country” without a strand of barbed wire to be seen. For him, this visit was a return to yesterday. He wore his nostalgia on his sleeve, and sentiment like humor was a defining quality of his paper talk. He could move from jokes to longing in the same letter. His exchanges with Stanford, for example, were charged with strong emotions. “You have a good memory and knew the country when it was worth knowing and men good ore bad that were regular men,” he told Stanford. “Write about them and the land they lived in when the nester turned this country grass side down the west we loved died She was a beautifull girl that had many lovers but today thair are only a fiew left to morne her . . . the man betwene the plow hand[l]es was never a romance maker and when he comes history is dead from now on montana has no history so do your damdist.” Looking back on its early days, even Havre seemed like heaven to him.

F. A. Meanea was a saddle maker in Cheyenne, Wyoming. Russell had used one of Meanea’s saddles for almost 20 years, but by 1905 was ready for a new one. (This letter, to the best of Big Sky Journal’s knowledge, has not been previously published.) The Rees-Jones Collection

As Indians came to figure more prominently than cowboys in his art, Russell refined a basic conviction: They were the original American patriots, “the onley real American[s],” and “the history of how they faught for their country is written in blood a stain that time cannot grinde out.” “Playing Indian” — dressing up in wigs and blankets and adopting a Native name (he was Ah-wa-cous, The Antelope) — defined his artistic strategy. It was the picture and story side of tribal life that attracted him. Like his buffalo skull emblem, Native Americans symbolized “the West that has passed.” “They have almost gon,” he wrote, “but will never be forgotten.”

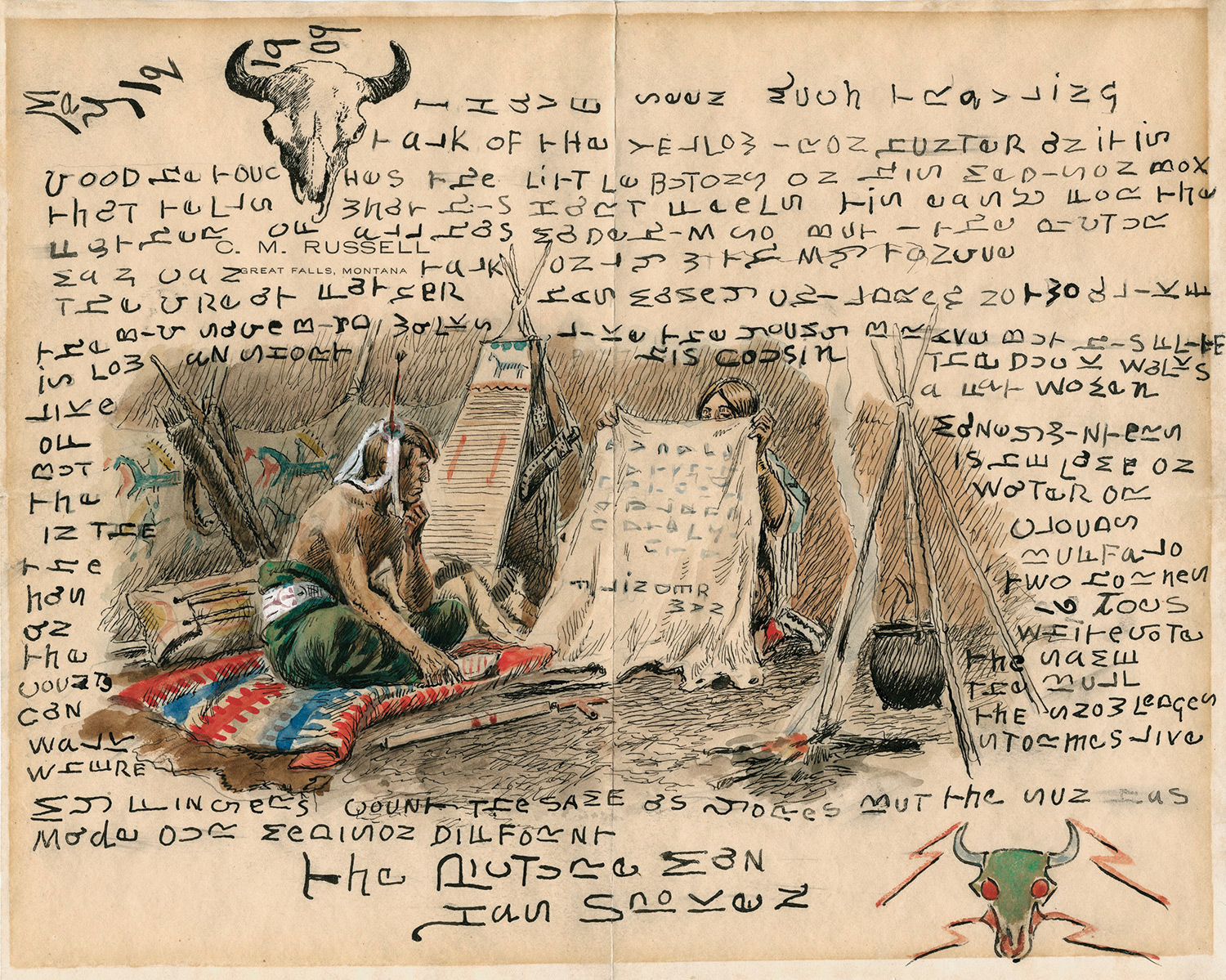

Present day realities were not his artistic concern, but through Frank Linderman he was enlisted in the campaign to secure a home for Montana’s destitute population of Canadian Chippewa and Cree. It culminated successfully in 1916 with the establishment of the Rocky Boy Reservation. By then, Linderman had published his first book, a collection of tribal tales, Blackfeet, Cree, and Chippewa, under the title Indian Why Stories. From the outset, Russell, who illustrated the book, had encouraged Linderman’s literary ambitions, and in 1909 had sent him an ingenious letter imitating a Cree syllabary in which he compared the variant gifts of writers and artists. He signed off, “The picture man has spoken.”

“Playing Indian” may seem a questionable practice today, but then it was a gesture of honor by the leading figure in a campaign for racial justice.

How do we explain the continuing popularity of Russell’s illustrated letters in an age no longer smitten with the Old West? Their charm has survived the years because Russell, despite attention and acclaim, remained a humble man — as “real as a toad-stool,” Linderman said — whose grousing on behalf of yesterday seems more prescient than outdated today. He lived by the maxim that no one is important enough to think he’s important, and that belief shines through in his letters. It helps account for their enduring appeal.

A 1909 Russell letter to writer Frank B. Linderman was formatted to resemble a Cree syllabary. David and Sandra Solberg Collection

A 1909 Russell letter to writer Frank B. Linderman was formatted to resemble a Cree syllabary. David and Sandra Solberg Collection

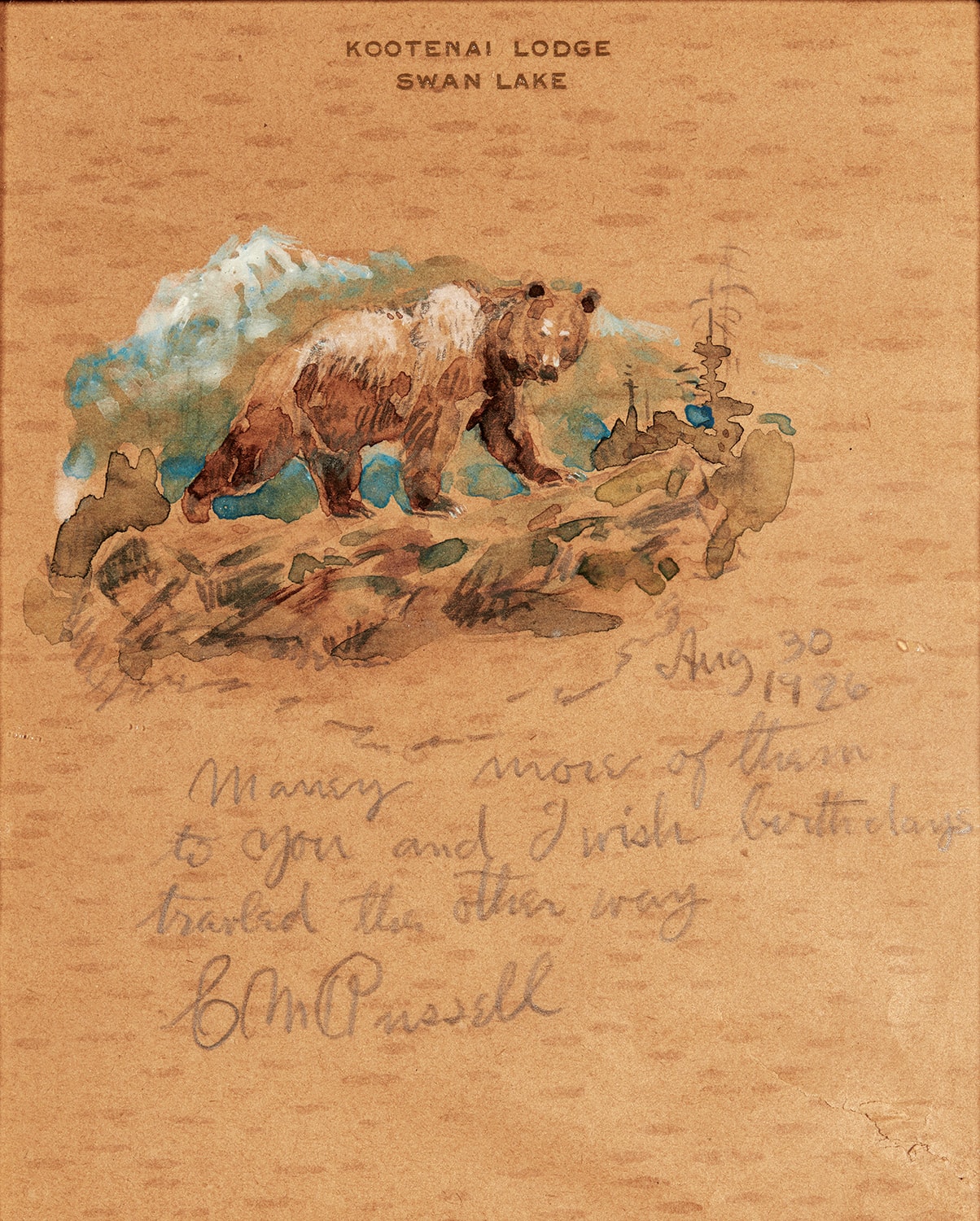

Forgers have tried to replicate Russell’s wobbly hand, hit-and-miss spelling, and marvelous illustrations. They fail because they aren’t Charlie Russell. He had a distinctive voice, a way with words, and something to say when he talked on paper. Of a cowboy pal who “never was verry slender through the flanks” and had put on weight over the years, he noted “you could eat a sandwich while you walk around the middle of him.” A birthday card from Josephine Trigg, their next door neighbor and confidante in Great Falls, brought this response from Los Angeles: “Old Dad Time trades little that men want he has traded me wrinkles for teeth stiff legs for limber ones … but cards like yours tell me he has left me my friends and for that great Kindness I forgive him.” Two months before he died, Russell sent Louis O. Evans, co-owner of Kootenai Lodge on Swan Lake, a birthday greeting with a watercolor of a backward-glancing bear and the wistful wish that birthdays “travled the other way.”

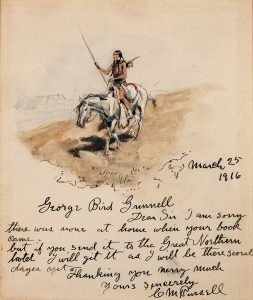

About 450 Russell letters are known to exist. Others are still out there awaiting discovery. A few treasured by descendants of the original recipients have never been offered for sale despite the hefty prices they command, and are effectively out of sight. Others have surfaced and then dropped from view. A Russell letter to George Bird Grinnell, “father of Glacier Park,” is a case in point. The two men were well acquainted by 1915 when Linderman dedicated Indian Why Stories to Russell, “the cowboy artist,” and Grinnell, “the Indian’s friend,” and “to all others who have known and loved old Montana.” Grinnell envied Linderman Russell’s contribution as illustrator. The next year, when Russell was exhibiting in New York, he stopped by to drop off a copy of his own compilation, Beyond the Old Frontier. Russell was absent at the time, but sent an illustrated thank-you note that Grinnell tucked into his copy of Linderman’s book. He could not find it in 1928 when Nancy Russell wrote soliciting material for Good Medicine, her compilation of Charlie’s letters. Grinnell concluded that he had not kept it, but it popped up again in 1952 when his library — including his copy of Linderman’s book with the letter laid in — was sold at auction, only to drop out of sight once more. Having since reappeared, it now ornaments the finest Russell collection in private hands, attesting to the enduring bond among those who knew and “loved old Montana,” and those who love it to this day.

Russell’s brief letter to George Bird Grinnell, “the father of Glacier Park,” made up in visual eloquence what it lacked in length. Petrie Collection, photograph courtesy of Jeff Wells, Denver Art Museum

That, too, is the appeal of Russell’s paper talk. He has been gone 90 years now, but on paper he speaks in the present tense. In a busy, high-tech world often impatient with the past, gallery-goers pause in front of a framed Russell letter and take the time to relish his sketches and puzzle out his prose. It’s a victory for a man who cherished a slower-paced world. He liked to sleep by the creek at Ballie Buck’s ranch outside Augusta. “The creek makes the best sleep music,” he wrote. “It sings and sings, and while I’m tryin’ to figure out what it’s singin’, I go to sleep.” To artist Phil Goodwin, bereft by the death of his mother, Russell offered the solace of another visit to Bull Head Lodge. Come, he said, “if you want the big hills that ware white robes and where the teeth of the world tear holes in the clouds the trail to my lodge is not grass grone and my pipe will be lit for you.” Millennials can still fall asleep beside singing brooks, and find solace in the out of doors. Come to Glacier National Park’s mountains and rest your worries, Russell told a World War I veteran. “Drop that smoking gun of yours and com over the top not to no mans land but to Gods country you and yors will find a camp thair not far from the gun sights pass where your welcom its a good place for a tired soldier where great mountions draped in white stand gard and clean rivers have murmered tails of peace to the big hills since time began.” He could be speaking to any weary sojourner today.

No Comments