16 Feb Guide Schools of the Northern Rockies

WHAT MAKES FOR A GOOD FLY FISHING GUIDE?

Start with catching fish, of course. That’s the baseline. Or more to the point, showing us how to catch fish. Tie on a fly, point us (sometimes literally) in the right direction, row close (but not too close), tell us to mend, mend, mend dammit, then congratulate us on our … whitefish. “Nice one. Natives, after all. Put up a good fight, don’t they?”

Catching fish, and affability. They have to be able to throw a good loop and have some talent behind the sticks, some basic entomology — the lifecycle of a caddis fly — 10,000 hours at the vice, a fondness for turkey sandwiches and an ability to resist the first beer until after they’re off the river. You have to be able to fish in the same boat with the guy for eight hours and not think he’s an ass. Now take those talents and translate them, package them, pass them along to us, the weekend warriors, arthritic retirees, the aspirant up-and-comers. Do it with a forbearing smile.

Most of all, the best guides teach us something. Start with “What bird is that?” and end with tips on a steeple cast. For that one day on the Yellowstone or the Missouri, they’re professor, life coach, chef, referee. Back in February when you booked your day, $450 felt like a hit. But at the end of it, disassembling your rod at the takeout … what else would you have spent that money on? What else could possibly have given you better bang for your buck? Feels like a deal.

It’s improbable, what a good guide does. For that one or two days a year, they teach us how to be better fishermen.

But who taught them?

In the northern Rockies, and especially if your guide is newer to the business, chances are pretty good that he or she came out of one of three different guide schools: Pat Straub and Garrett Munson’s Montana Fishing Guide School; Dan, Jeff, and Pat Vermillion’s Sweetwater Travel Guide School; and Western Rivers Guide School in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, administered by WorldCast Anglers. Together, these three schools (along with one or two others), provide a firmament of classroom instruction, practical advice, and hands-on experience that has served as a launch pad for any number of romantic, underpaid careers on the river.

Based in Big Sky and Helena, Montana Fishing Guide School is the newer kid on the block. Straub and Munson, co-owners of Montana Fishing Outfitters (Straub and his wife also own Gallatin River Guides, a storefront in Big Sky), had their first official guide school session in March 2013. “We had six people in that first school,” Straub said. “And about half our time was spent in Bozeman, and half on the Missouri.” It became a pattern, splitting their time between the region’s famous rivers, bouncing from the Missouri to the Madison to the Yellowstone to the Gallatin. Since then, their business has grown by leaps and bounds, but they’ve held to the same basic pattern. “In 2017, we have 10 sessions scheduled. And we usually have about six students a session. That’s kind of the perfect number for us, six to eight.”

All three schools have certain aspects in common. They all teach master level fly tying and casting, often bringing in experts to augment the instruction. They teach the basics of fly fishing as a business, and how to navigate the paperwork involved with outfitting and guiding. How to back up a boat trailer and how to row for a fly fisherman. But in addition, each of the three guide schools also has its areas of specialty. Straub and Munson, for instance, make an extra effort to reproduce real world conditions, to cater to specific student requests. The school runs for seven full days, and, as Straub said, “We’re on the river every day. Some folks want to be on the boat all seven days, and some folks want to learn the nuances of wade fishing and spring creeks and technical waters on foot. What we feel is great about our curriculum is that we have the flexibility to cater to the students.”

He thought about it, then continued, “Our school is really meant to give folks a look behind the curtain. Where we fish each day often depends on the conditions of that day. So the curriculum stays consistent, but the fishing practicum, the technical fishing knowledge, varies. The students are exposed to a new angling experience each day. It’s likely that we might fish the upper Madison on Tuesday, the Yellowstone on Wednesday, and the Missouri on a Thursday.”

Straub and Munson, like the other schools’ instructors, also place a focus on conservation as an essential aspect of the guide’s life. “We brought in Paul Roos for our first session,” Straub said. “Roos is a longtime Montana outfitter, one of the original Smith outfitters, and someone that Garrett and I really respect. He mentored us, and we like his philosophy about guiding and conservation and the idea that being a steward of the resource is as important, if not more important, than being a good guide and making a living in the business.”

The vermillion brothers — Dan, Pat, and Jeff — own Sweetwater Travel Company, based in Livingston, Montana. Sweetwater helps arrange fly-fishing excursions around the world, including trips to Alaska for trout and salmon, taimen in Mongolia, peacock bass in Brazil, payara in Venezuela, and bonefish, tarpon, and snook, in Florida, the Bahamas, Nicaragua, Tahiti, and Costa Rica. As an aspect of this company, the Vermillions also run their Fly-Fishing Guide School. They manage to train between 90 and 110 students a year in 12 sessions, each one week at a stretch.

“Our first guide school was in 1998,” Dan Vermillion said. “We ran that out of our lodge in Alaska. When my brothers and I first started guiding, we were 18 or 19 years old, and we thought we knew about fishing. But turns out there were things we’d missed. We didn’t know much about operating boats, for instance. Motor repair, that sort of thing. And consequently our first few weeks guiding in Alaska were rocky. You make a lot of mistakes. We look at our guide school now as a way to give our students a way to minimize the stress and the mistakes they make when they start. Give them a good understanding of what the business is like, what guiding is like, before they make a career change.”

The brothers moved the guide school to Montana in 1999. “We realized that this would be a good service that could be compelling and appealing to a lot of kids that are looking to get into the fishing business.” They operate their classes on the Yellowstone River, not far from Big Timber, as well as on the Bighorn out of Fort Smith. These stretches of river allow them, uniquely, to incorporate jet boats into their curriculum. “We take them out on a jet boat, teach them rudimentary maintenance. The stuff you need to know how to fix. How to read a river, jet boat etiquette. We also take them out on drift boats, of course. They have an instructor in each boat, and they row each day. Most of the guys are very interested in this.”

The Vermillions, Dan said, run their guide school a little like a fishing lodge. “Everyone helps out. That’s one of the things we want, to make sure the kids know what they’re getting into if they go to work for a fishing lodge. You do a lot more than just guide. We teach them how to build a business, how to develop relationships with clients. The last day, each student is in charge of their boat and acts like a guide. We have them tell us how to fish, where to fish, and give us tips along the way. At the end of the course, we help them build a resume, and put them in touch with lodges that are looking to hire.”

In 2000, the newly-created Jackson, Wyoming-based WorldCast Outfitters took over the Western Rivers Guide School. The school previously had been a fairly casual affair, according to C.G. Sipe, head of outfitting for WorldCast, who characterized it as “kind of a demand-driven concern.” But WorldCast took it to the next level, and they now offer three different schools per year. “At each school, there are five instructors and 10 students,” Sipe said. “We used to offer only two guide schools in the spring, but then we started to see that there were people who weren’t necessarily interested in becoming guides but wanted to learn how to row or tie flies. We started a fall school, and that’s tailored more to people who want to do it on their own.”

Based on river flows and student ability, Sipe and his colleagues spend time on the South Fork of the Snake, the Henry’s Fork, the Snake, or the Teton River. The first day of school is in the classroom. “We teach everything from reading the river to knots to how to teach a fly casting lesson to trailers to boat rigging, making sure that people know how to throw a throw rope properly. We have an entomology professor come in, and we give a talk about guiding from a business perspective. We always get a nonprofit to come in, either Friends of the Teton River or Trout Unlimited, somebody to talk about the conservation side of the business.” The second day is their first water day, and then they do another classroom day. “And then the last four days are all on the water.”

Sipe said that every guide who ends up working for WorldCast Anglers goes through the guide school at some point. “Even if they’re already an established guide, we ask that they go through our course. It helps introduce them to our culture, to who we are.”

Western Rivers also offers formal certification. “Everybody gets a manual, and at the end they get a diploma of completion, and in the rare instances that we feel we want to endorse somebody, they get a certification. That’s our stamp of approval that says that a given student is ready to guide the next day. It’s rare for us to give those out. A big year would see four or five certificates.”

In october last year, I met Pat Straub and one of his fall classes in a conference room at the Bozeman Holiday Inn. It was 8:30 in the morning, and one of Straub’s instructors, Craig Boyd, was just finishing up a session on the well-appointed gear bag. A subject of considerable complexity, as it turns out. Boxes for streamers, hoppers, nymphs, dries. Spools of tippet material bought fresh that year. Lead and floatant and sunscreen. An army marches on its stomach but a guide earns his tips out of his gear bag.

Twenty minutes after that mini-lecture, Straub stood in the parking lot beside his drift boat, checking text messages. A half-circle of students and a couple of guide instructors stood waiting. Among others, there was Laurel from Pennsylvania and Laura from British Columbia. There was Matt from Florida, a saltwater guy, and Don who was a student at Montana State University. “I live to fish, man. I’m here because I just want to be better at it.” My role for the day was to serve as a client, in air quotes. I would be the guy in the boat who was something less than professional. Straub tucked his phone away and said, “Looks like the Yellowstone’s off-color. I’m calling an audible, we’re going over to the Madison.”

Two hours later, at the Lyons Bridge, one of the students noted my camera, my Super Glue-repaired Hodgman waders. He glanced around and said, amiably but with an edge to it, “You’re really kind of like the perfect fake client, aren’t you? Big camera, beat up old waders. I mean, talk about getting your mileage.”

Later, from the back of the boat, Straub said, “Guides really need to cultivate a rapport with the clients. They need to enjoy the teaching. Enjoy seeing somebody else catch a fish.” He looked past the student pulling at the oars, positioning us in the current. Eyed my waders. “You gotta admit, though: Those Hodgmans have seen some miles.”

“They’ve got character, man. Timeless style.”

“Yeah, I can see that. They’re kind of like the El Caminos of waders.”

“Exactly. Thank you.”

My novitiate guide for the day, the student at the sticks, had spent most of his professional life as a hunting guide, first in the Winds down in Wyoming and then in the Bob Marshall, where he’d had his own outfitting service. He was a good fly fisherman and an experienced hunting guide, but weak where the two came together: fishing guide. He was there primarily for help navigating the bureaucracy of licensing, the paperwork burden put on guides and outfitters by the state. Also for rowing instruction.

The fishing was slow, but it didn’t matter much. During the course of the day, I watched Straub pass along genial advice about boat placement, rowing techniques. The crawl stroke. And at the end of it, at the takeout, I watched one of the other guides help Laura back the trailer down the ramp, pointing it toward one of the waiting Clackas.

I stood back with my camera, snapping photos while the students hung out by an open tailgate, hashing over their day. It occurred to me that among the other benefits of guide school, they provide a start at a social network. Like most businesses, a good part of the success or failure comes courtesy of your peers, from other guides who will be available to pass along river information, give you the skinny about local shuttle services, that sort of thing. It’s a tight community, made tighter still by the subtext of competition, the push and pull of egos. As distant as various fishing destinations might be — Rock Creek, the Missouri, the Yellowstone, Henry’s Fork, the Snake — comes down to it, the guiding community is still just one big sewing circle, tied together by microbrews, Copenhagen, and late model Toyota Tundras.

The price tag for each of these three guide schools runs between three and four grand. For that, you not only get a week of fishing and tips and tricks from some of the best guides in the business, you also are afforded access to an otherwise closed circle of professionals. Feels like a deal.

- During a 2016 October session, Pat Straub and Garrett Munson’s Montana Fishing Guide School met on the Upper Madison River, with curriculum covering the well-appointed gear bag, how to offload your driftboat from its trailer, and tips on the best brown-bag lunch. Photo by Allen M. Jones

- Based in Jackson, Wyoming, and Victor, Idaho, the Western Rivers Guide School, operated by World- Cast Anglers, regularly conducts its classes on the Snake River, the South Fork of the Snake, the Henry’s Fork, and the Teton River. Photo by Corey Kruitbosch

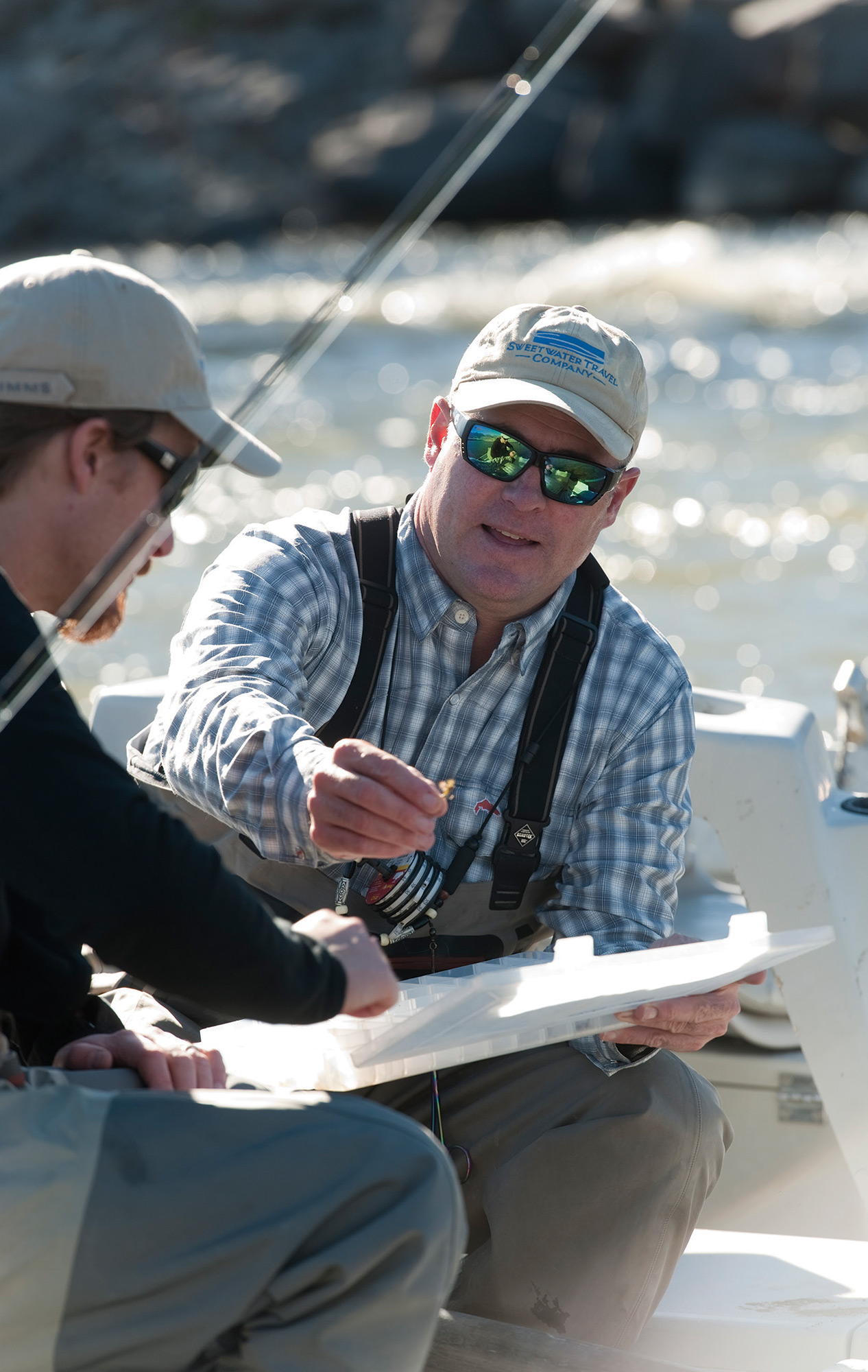

- As Vermillion demonstrates, a successful guide manages to teach everything from proper casting technique to reading the water to fly selection. Photo by Lynn Donaldson

- As Vermillion demonstrates, a successful guide manages to teach everything from proper casting technique to reading the water to fly selection. Photo by Lynn Donaldson

- As Vermillion demonstrates, a successful guide manages to teach everything from proper casting technique to reading the water to fly selection. Photo by Lynn Donaldson

- During a 2016 October session, Pat Straub and Garrett Munson’s Montana Fishing Guide School met on the Upper Madison River, with curriculum covering the well-appointed gear bag, how to offload your driftboat from its trailer, and tips on the best brown-bag lunch. Photo by Allen M. Jones

- During a 2016 October session, Pat Straub and Garrett Munson’s Montana Fishing Guide School met on the Upper Madison River, with curriculum covering the well-appointed gear bag, how to offload your driftboat from its trailer, and tips on the best brown-bag lunch. Photo by Allen M. Jones

- During a 2016 October session, Pat Straub and Garrett Munson’s Montana Fishing Guide School met on the Upper Madison River, with curriculum covering the well-appointed gear bag, how to offload your driftboat from its trailer, and tips on the best brown-bag lunch. Photo by Allen M. Jones

- Based in Jackson, Wyoming, and Victor, Idaho, the Western Rivers Guide School, operated by World- Cast Anglers, regularly conducts its classes on the Snake River, the South Fork of the Snake, the Henry’s Fork, and the Teton River. Photo by Corey Kruitbosch

- Based in Jackson, Wyoming, and Victor, Idaho, the Western Rivers Guide School, operated by World- Cast Anglers, regularly conducts its classes on the Snake River, the South Fork of the Snake, the Henry’s Fork, and the Teton River. Photo by Corey Kruitbosch

No Comments