26 Jul Julie T. Chapman

WESTERN WILDLIFE ART CAN HAVE a schizophrenic quality. Some is sentimental. A sunlit doe and fawns in a sepia-toned clearing. A black bear gamboling with her adorable cubs. You almost want to pet them.

Others are all snarl and snap. Imagine the grizzly in The Revenant frozen in mid-charge, incisors and claws filling the foreground. Or Charlie Russell’s wolf pack slashing at a hapless cowpoke and his horse.

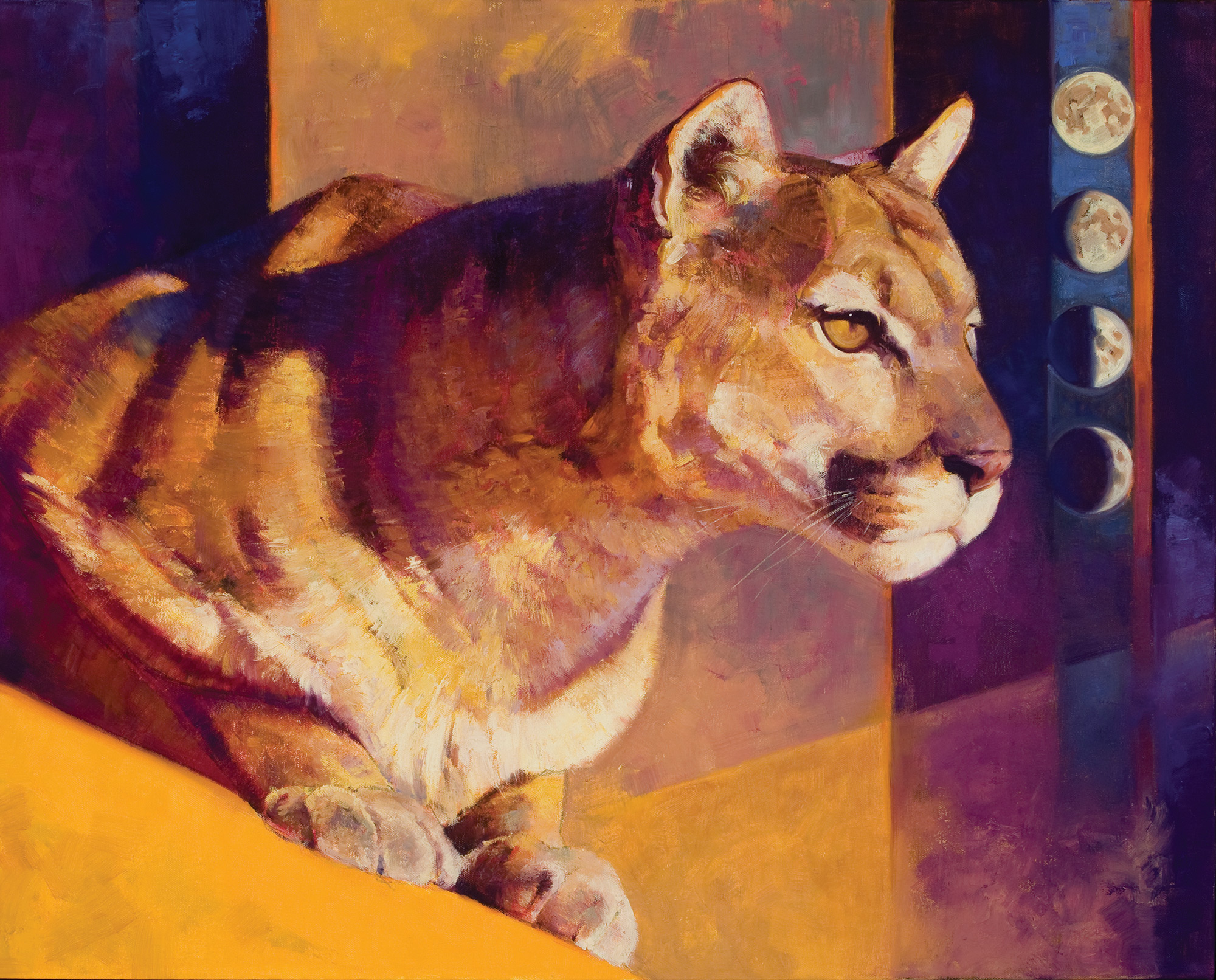

Julie Chapman’s work steers a respectful and realistic middle ground, more awe than awwwww. No one would want to pet her wolf, so fixated on his unseen prey that he practically vibrates within the frame.

“He’s keyed in,” Chapman said. “There’s some intensity.”

Her grizzly has yet to bare his teeth in a roar. He’s not a threat, not yet, but the way he peers upward, muzzle first, gives a viewer the notion that the bear is just a little too attentive for comfort.

Chapman issues a warning that too many visitors to Yellowstone forget to heed. “These animals,” she said, “they’re not tame.”

In fact it was a visit to Yellowstone that inspired her foray into wildlife art, expanding her work from her previous focus on the equine art that had sprung from her own impressive horsemanship.

She competed for years in three-day events, the rigorous competitions that feature rough-and-tumble cross-country courses over fences and through water, the formidable challenge of stadium jumping, and the precise and delicate maneuvers of dressage.

An engineer by training and career (marketing, and research and development with Hewlett-Packard), she’d always sketched horses, a hobby that morphed with no formal training into horse portraits in oils and other media.

Then, in the mid-1990s, came the Yellowstone vacation.

“Whoa!” she recalled her reaction. “There’s big animals here! And they’re not horses. It blew my mind.”

And it blew her art into a whole new dimension. In 1997, she painted an elk, and entered it in the now-defunct Arts for the Parks competition featuring artists whose work captured the spirit of the national parks.

The elk was chosen as one of the top 100 entries. “I was clueless,” she said of the significance. The ranking earned her a spot at a reception populated with gallery owners and collectors. People paid attention to her. And she started paying a lot more attention to her art.

She entered Arts for the Parks every year, each time placing in the top 100, until 2003 when she won the $50,000 grand prize.

“That was a kick in the butt.” She said goodbye to HP and began to focus full time on her art. Oh, and she moved to Montana.

Today, Chapman and her husband, Paul, live well off a gravel road up the Ninemile west of Missoula, with plenty of room for the four German shepherds that replaced the horses Chapman used to school. Now, when she’s not working at her art, she and the dogs compete in agility courses. But the art, created in a sun-splashed studio above a large garage, takes most of her time.

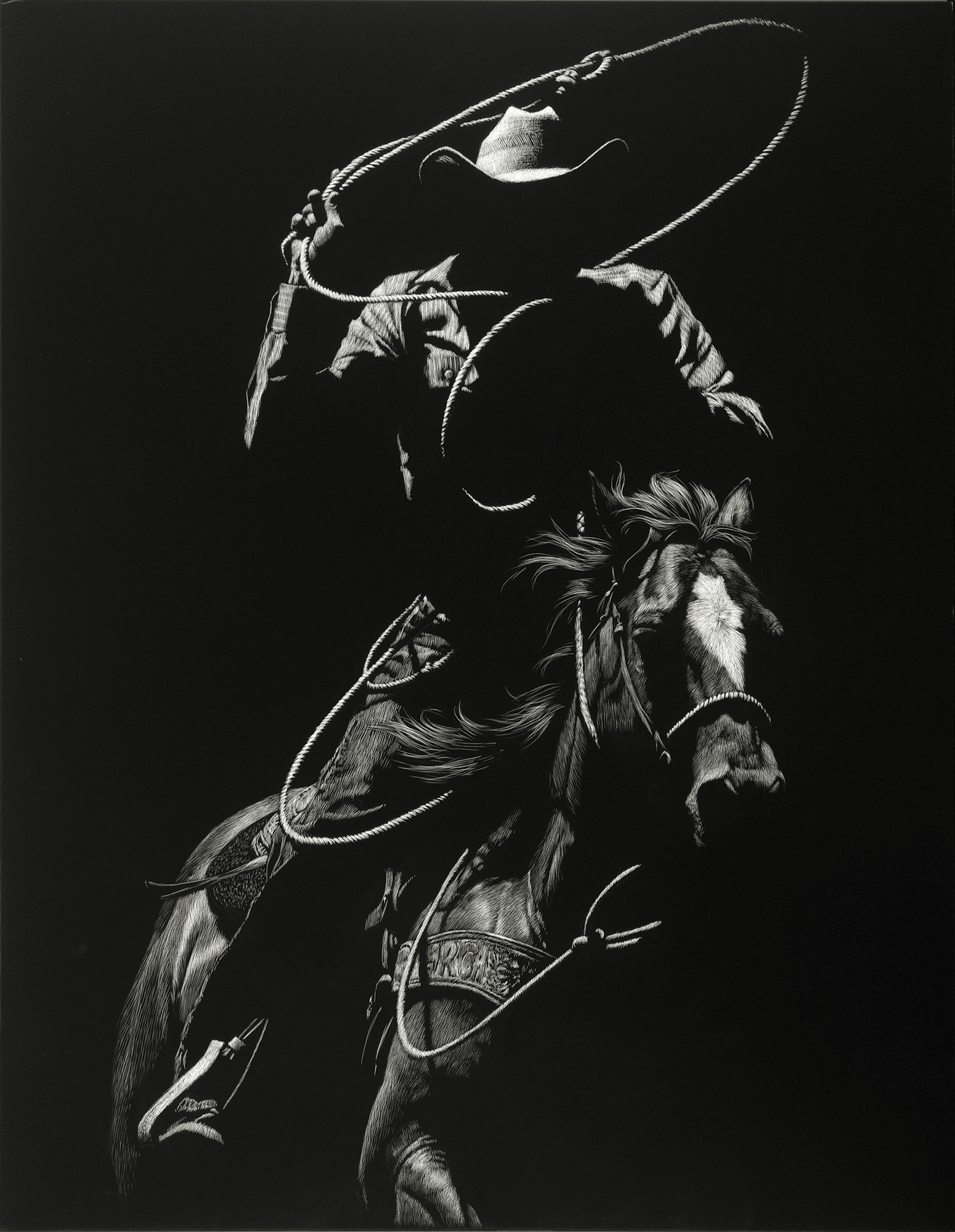

On one wall hang some of the completed scratchboards, a medium she turned to about five years ago. Another scratchboard, of a white horse, awaits completion on an easel. “Drawing with light,” Chapman calls her scratchboards. With detail, too. The medium requires infinite patience as an artist scrapes away the board’s coating, line by hair-thin line, to create the image.

“It’s really three-dimensional,” she said. “The image comes out of the board.”

That quality is what drew Lisa Roellig to Chapman’s work, which she and her husband Mark first saw at the annual Russell Exhibition and Sale in Great Falls. Now they have six of Chapman’s scratchboards, and anticipate buying more for a condo in Vail.

“How do you explain to someone what connects you to a piece?” said Roellig, who proceeded to do just that. “You don’t have to have a spotlight on it. Her pieces look great without light. And, they balance out our other pieces,” which are mostly colorful works by other Western artists.

A large scratchboard mountain lion, the first of Chapman’s pieces they acquired, remains her favorite.

Although Chapman saw her first large wild animals — “charismatic megafauna” as they’re sometimes called — in Yellowstone, she usually looks closer to home when it comes to the predators she portrays.

The Triple D game farm in Kalispell has wild animals such as bears, wolves, mountain lions, and even a Siberian tiger, in natural settings, as well as horses and cowboys, for photographers and artists. “Trained,” the Triple D says of their animals.

Chapman adds an important qualifier: “Trained, but not tame.” Now she leads wildlife art workshops at the Triple D. She’s also traveled to Africa, the source for most of her images of more exotic animals.

Chapman photographs the animals extensively before she begins a new work, just as she does with her horse portraits. A wall of files takes up one wall of her studio, a throwback to the day when she preserved those images as slides. “I take millions and millions and millions of photos.” Then she weeds them out.

She pointed to the files —“I probably have 30,000 slides,” — then to a laptop, “and 100,000 digital images. I do a lot of mocking up in Photoshop.”

That helps her capture the detail that distinguishes her work. But her art is far from photographic, a stroke-by-stroke rendering of the images captured by the camera. Take an oil painting. Rather than placing, say, a rodeo cowboy in a realistic arena, all dust beneath and peeling wooden fence in the background, her bareback rider flies high against bands of beige, red and black that blur into one another.

In another oil, a charging bison emerges from a field of beige and blue shading into purple and black, suggesting twilight.

“There are so many artists who do fabulous landscapes,” she said. “I’m not interested in setting. The animals are my landscape.”

Chapman’s works are sold in galleries around the West — Montana, Utah, Wyoming, and Arizona — as well as in England. About 10 to 20 percent of her work comes from commissions. She spends up to six weeks each year on the road, traveling to various shows, such as the Southeastern Wildlife Exposition in Charleston, South Carolina. She estimates that at least half her time, if not more, is spent marketing.

“To be successful,” she said, “you’d better know how to run a business.”

These days, she said, “I’m in a fever of experimentation … doing a lot of pour paint and high-flow acrylics in water.” She shows off a horse head of many colors, all flowing into one another and beyond the lines.

“That girl has grown so much,” said Roellig. “She’s getting better and better and better. You can see movement [in her work]: strong, bold movement.”

Much like Chapman herself. At 53, she’s just getting started on the next phase of her artistic career. “I’m playing with the pure color of fluid acrylics,” she said.

When she says it, you get the feeling that the most important word in that sentence is play. It’s a word that captures her exuberant attitude toward her art, and the sense that there’s so much more to come from Julie Chapman.

- “Honcho” (detail) | Scratchboard | 20” x 30”

- “Seduction” (detail) | Scratchboard | 24” x 24”

- “Moving Off” (detail) | Oil | 24” x 30”

- “Roper Arabesque” | Scratchboard | 18” x 14”

- Artist Julie T. Chapman with her 40” x 30” oil, “Girlpower.”

- “Paint Abstract in Bay” | Oil | 40” x 20”

No Comments