08 Feb Books: Reading the West

All the Wild that Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, and the American West by David Gessner (W.W. Norton, $26.95) is a fascinating new book — part biography, part eco-travel guide and part literary criticism. Trailing in the footsteps of two of the great writer-environmentalists of the 20th century, the disparate Edward Abbey and Wallace Stegner, Gessner weaves together their life stories with their widely different approaches to writing and environmental activism. The result is a book that asks new questions of how those who think about the future of the West should respond to its challenges.

An award-winning environmental essayist in his own right, Gessner travels the ground trod by the two authors. The result reinvigorates their work by putting it into the contemporary context of a region struggling with climate change, drought, massive wildfire, drilling, fracking and political polarization. As he follows their trails from Saskatchewan to Utah and beyond, he considers their distinct styles, juxtaposing Abbey’s call to guerrilla-style activism with Stegner’s more formal and disciplined approach. Gessner seems to be asking how his heroes would respond to today’s challenges, and how a new generation of activists might take up their mantles.

Through interweaving the two complementary yet competing biographies and recounting his own adventures, Gessner also asks his readers to reconsider the work of these visionaries, perhaps driving new interest in their historic work. It’s an entertaining and inspiring journey through the American West.

In 2003, Annick Smith traveled from her rural Montana home to Chicago’s North Side on a journey to pick up her nearly 100-year-old mother for a trip to their family beach house on Lake Michigan. Accompanying Smith was a 95-pound chocolate lab, Bruno. More than a decade later, Smith has woven together a beautiful memoir about that trip, recalling the larger themes of family and love at the heart of her journey. Crossing the Plains with Bruno (Trinity University Press, $17.95) tells the story of two weeks driving across the American West and through its heartland, continuing the story of Smith’s fascinating family history and offering new insights on human nature and relationships.

Told as a series of meditations on memories triggered by encounters on her road trip, Smith tells stories of her Hungarian-Jewish family and her childhood in Chicago, her journey into the West and into becoming a writer; she writes of her relationships with her sisters and her aging mother, with her sons and partner. Reflecting in the introduction on the nature of writing, she muses, “As I head toward eighty, it is easy to fall into stories about nostalgia and loss, but the world I encounter is as present as anyone’s.”

And, indeed, it is Bruno’s part in the journey — sitting in the passenger seat of her secondhand white SUV — that ties the story to the present as she drives for two weeks through the tiny towns and open spaces between Montana and Chicago. His needs keep the story present and on track, just as Smith’s beautiful writing and introspection keep her history relevant and fresh.

The lovely Bruno, Smith’s companion on her physical trip through the heartland and her emotional trip through the memories triggered by travel, died before she completed this manuscript. Just as Smith’s “memory and flights of fancy” (as she describes this memoir) tell much more than the story of her family and relationships, the story of Bruno recalls more than a wonderful companion but delves into the nature of relationships between humans and their pets.

Our Only World: Ten Essays by Wendell Berry (Counterpoint, $24) invites readers into the mind of the great novelist, poet, essayist and activist, bringing together 10 of his recently published essays on topics ranging from scientific analysis and specialization to the Boston Marathon bombing to forestry. Over his career, which has spanned more than half a century, Berry’s greatest strength as an essayist and critic has always been his willingness to confront questions head on — and in these essays he frames the questions so as to create a cogent set of topics that gets to the heart of issues facing America as we tread more deeply into the 21st century.

The first essay, “Paragraphs from a Notebook,” introduces the theme that inhabits each of the varied essays in this book: “We need to acknowledge the formlessness inherent in the analytic science that divides creatures into organs, cells, and ever smaller parts and particles, according to its technological capacities.” From the start, that essay — which strings together pearls of thought from the writer and sources stretching from the Book of Job to Ezra Pound — sets the tone for the rest of the book. Berry asks readers to consider a broad view and holistic approach to confronting the challenges and difficulties of life on this planet, as we strive to preserve our only world and ourselves.

Berry uses the central ideas of this first essay to make connections between the disparate topics throughout the rest of the book, forming them into cogent musings on soil conservation and abortion rights and gay marriage. Those skillful connections take this book from the category of “collection from a famous and well-known and respected thinker” to prescriptions for creating a more sustainable world. It is encouraging to read these criticisms and this beautiful writing, and humans would benefit from taking Berry’s words to heart:

“To learn to meet our needs without continuous violence against one another and our only world would require an immense intellectual and practical effort, requiring the help of every human being, perhaps to the end of human time. … This would be work worthy of the name ‘human.’ It would be fascinating and lovely.”

Brimming with sincerity and a thoughtfulness that belies what must feel like a career of shouting into the wind, this beautifully written book has much to offer and perhaps much to argue with, but above all it should be read with a view to broadening minds and ideas in an increasingly narrow world.

OF NOTE: Books, Music, Movies & More

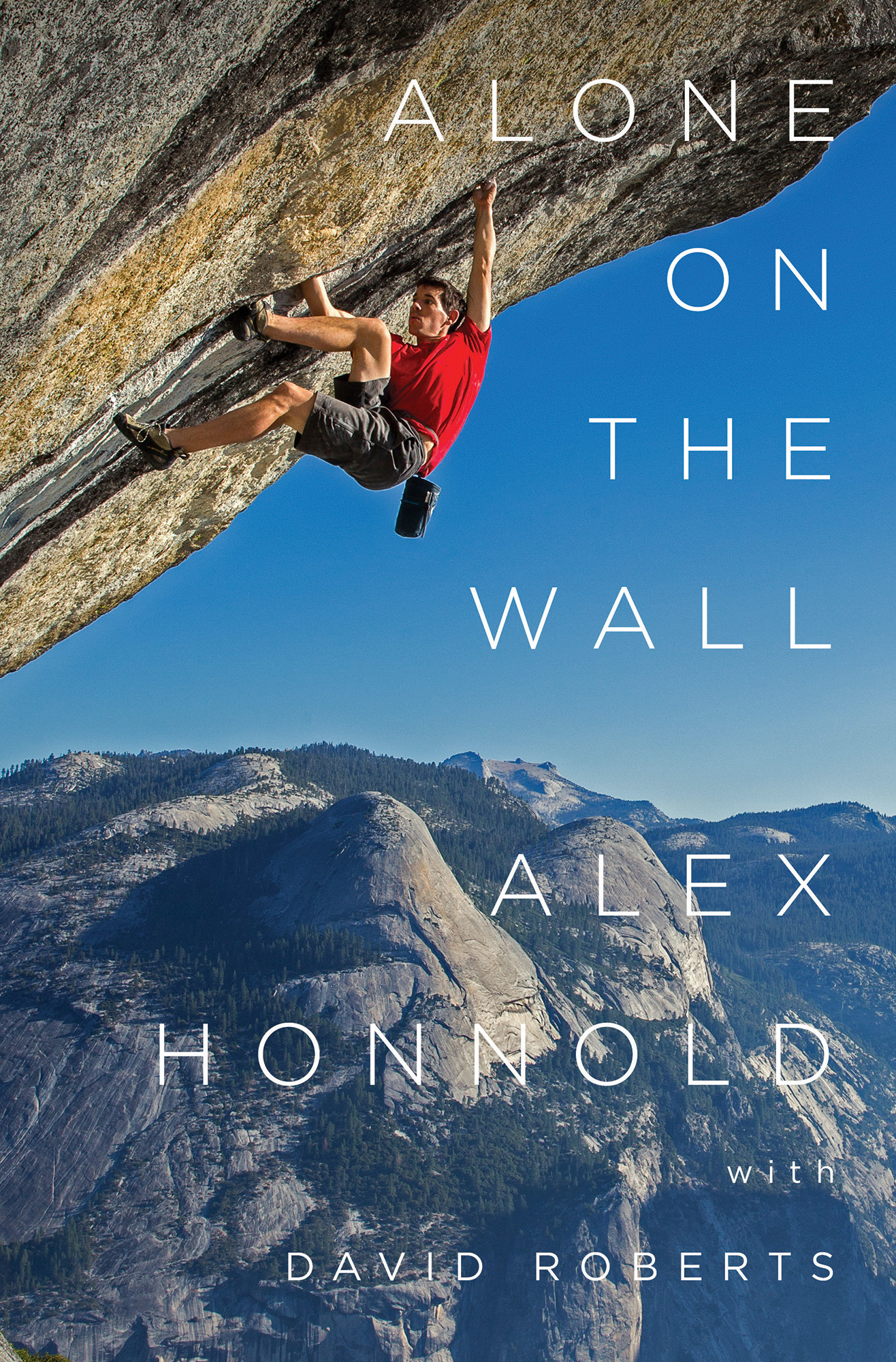

The seven ascents that world-famous solo climber and adventure athlete Alex Honnold and author David Roberts recount in Alone on the Wall (Norton, $26.95) create a portrait of the visionary rock climber and of some of his most famous and harrowing free-climbs from Moonlight Buttress in Utah to the Fitz Traverse in Patagonia. An expert in free climbing and a holder of numerous speed records, Honnold has pushed the boundaries of climbing and has become best known for his free-soloing feats — climbing big granite without a rope, partner or hardware. In each of the seven chapters of the book, he draws the reader into his pre-climb thoughts and preparations, recreating the inner world of the climb itself to give readers a glimpse of the sheer drama of hanging alone on the face of some of the most challenging climbing terrain in the world. Partly because each chapter is written in both Honnold’s and Roberts’ voice, each offering different perspectives, this book transcends the genre of climbing memoir, offering what feels like a more honest and balanced approach to the accounts and a more comprehensive analysis of what makes Honnold, and the culture of free climbing, tick.

On Fly Fishing the Northern Rockies: Essays and Dubious Advice by Chad VanZanten and Russ Beck (History Press, $19.99) is a book about fly fishing Montana, Utah, Idaho and Wyoming’s iconic streams and within the region’s inspiring landscapes. But while it is sometimes introspective and often inspirational, it’s not precious or pretentious. Alternating between essays by the two fishermen and friends, the book (which is illustrated with black-and-white and color photography, often featuring face-splitting grins on the faces of successful fisherfolk, their friends and family) is funny and joyful and not a little irreverent. Both of these writers bring exuberance and youth to their storytelling, and a modern attitude sprinkled with just the right amount of irony that’s refreshing in a fly-fishing book. But it also offers enough of the familiar and old-fashioned to join it in a chain with some of the great literature on the sport. It’s hard not to enjoy an essay about fishing that starts with the line, ”Here’s a story that may or may not be true.”

Montana Peaks, Streams, and Prairies: A Natural History by E. Donnall Thomas, Jr. (History Press, $21.99) is more than a survey of the habitats, habits, ranges and natural histories of Montana’s varied wildlife species. Thomas, a physician, fisherman, long-bow hunter and hunting guide — as well as the author of more than 20 books on outdoor topics — neatly categorizes species from marmots to bull trout to grizzlies, placing them appropriately in context within the food chain and in relation to both the landscape and the humans who also inhabit it. Color and black-and-white photography throughout the book offers visual interest, but Thomas’ personal affinity for and observations about his subjects are the real appeal of this volume. With entries ranging from hints on gathering and drying morel mushrooms to a tale of encountering prairie rattlers while wearing old waders, this comprehensive volume mixes science and experience, and offers inspiration for preserving the natural world.

Rinker Buck’s The Oregon Trail: A New American Journey (Simon and Schuster, $28) has become something of a national phenomenon since its publication, reintroducing Americans to one of the great epics of U.S. history: the story of the mass migration of settlers into the West over the 2,000-mile Oregon Trail. Buck and his brother Nick took to the trail, crossing six states in a covered wagon pulled by a team of mules, accompanied by a Jack Russell terrier named Olive Oyl. Buck’s recollections of their adventures, from fixing wagon wheels and axels to searching for water sources, bring new life to the journeys of the 400,000 pioneers who made the trip west in the years before the Civil War. Buck’s book has inspired a new level of interest in the trail and in the preservation of those stories, reinvigorating our understanding of the experience.

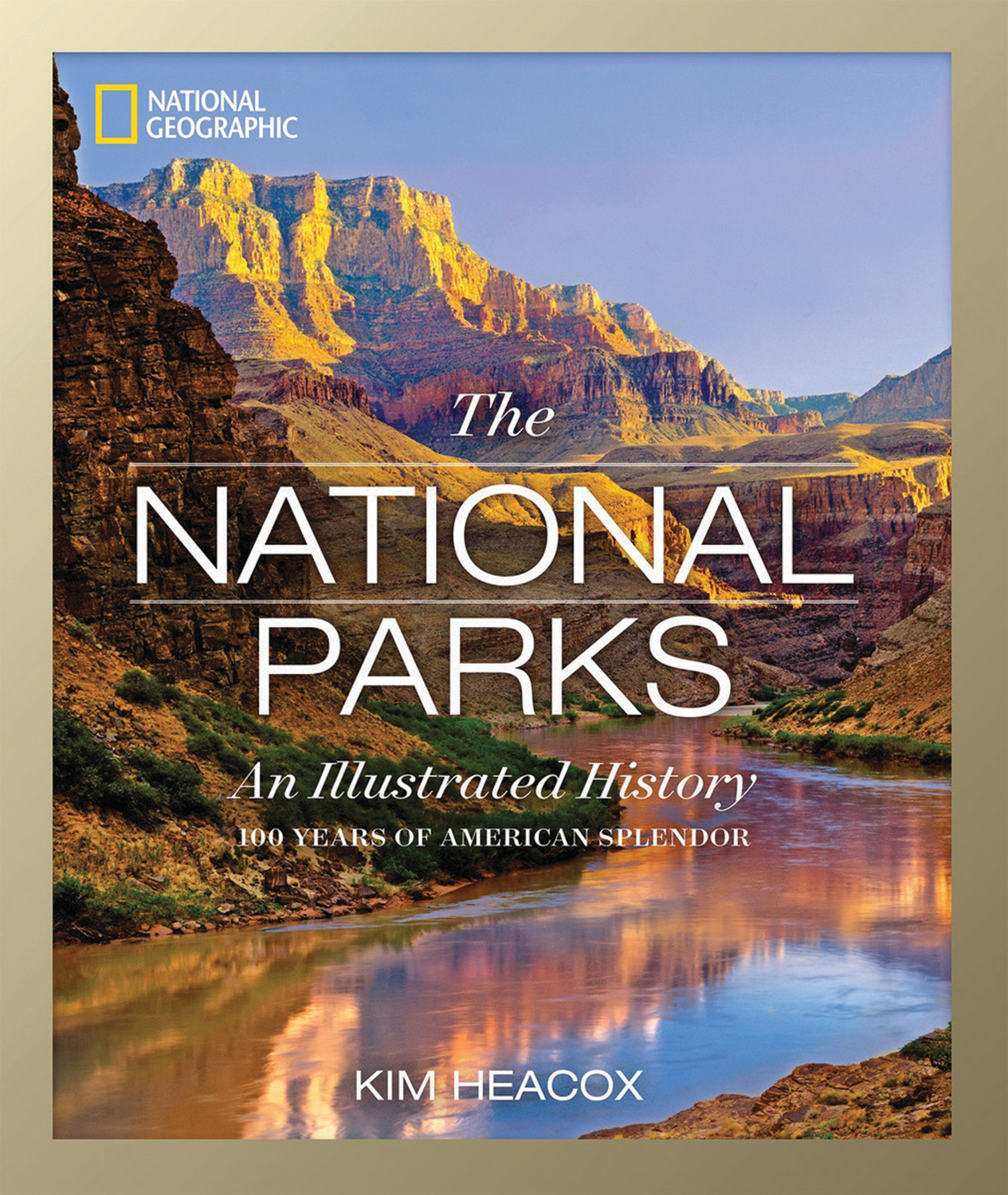

The National Parks: An Illustrated History by Kim Heacox (National Geographic, $50) is the latest tribute to the great American national park system. As a celebration of nearly 150 years of the national park concept, it succeeds handily, featuring page after page of the kind of fabulous photography that National Geographic is known for. Timed to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the founding of the National Park Service in 2016, this publication combines images from Acadia to Yellowstone with thoughtful and well-written histories of these places, telling the stories that make up the mosaic of their past. This is a classic, old-fashioned and appealing photo book, perfect for park buffs.

Custer’s Trials: A Life on the Frontier of New America by T. J. Stiles (Knopf, $30) treads again over the familiar ground walked by the iconic General George Armstrong Custer in a biography that examines Custer’s life in the context of his times, but goes beyond the caricature and seeks to offer a fuller portrait of the man. Stiles rightly points out in his preface that this story “begins with its ending.” The Battle of Little Bighorn, of course, has naturally become the focus of our gaze back at Custer’s storied life and career. This new book succeeds, however, largely because of its focus on his relationships and actions, his contradictions and his self-doubts even as his fame and celebrity rose during the years of the Civil War and after. Not a vindication of Custer, but a fuller portrait of a multidimensional man, this wonderfully written biography adds much to the existing canon.

No Comments