09 Feb A Simple Revolution

I FIRST MET YVON CHOUINARD on a brisk pre-dawn Idaho morning. Up before the sun to capture photographs, I entered the little camp house kitchen to see a fit, weathered man digging through the cabinets for a pan to boil water and make tea. It took a full two or three minutes before I realized the man I was idly talking fishing conditions with was the founder of that most revered mountain brand, Patagonia.

We sat on the porch, sipping tea, and chatted about Russian salmon fishing and tenkara philosophy while the sun rose over the Tetons, chasing away the night’s chill. As expected of the man famous for saying, “The more you know, the less you need,” he spoke eagerly about the minimalist approach to fishing that was preparing to sweep the country. He saw tenkara as a parallel for business — skill should replace quantity, and quiet awareness transplant rampant consumerism.

It’s an odd stance, perhaps, for a man who has made his living peddling outdoor clothing. Chouinard, or YC as the Patagonia crew calls him, founded Chouinard Equipment in 1965, crafting climbing tools as the world had never seen. His pitons were lighter, simpler and stronger than ever, and the outdoor community took notice. By 1972 the fledgling company was selling select outdoor gear inspired by European mountaineering designs. Around the same time, a new company name was sought — Patagonia — eliciting something rugged and inspiring and a bit off the map. Fast forward 42 years, and the brand is a veritable behemoth in the outdoor industry.

For the man who has led the charge, Chouinard is surprisingly humble. He’s an old-school gentleman; patient, soft-spoken, full of prodigious knowledge and incredibly, undeniably quotable.

“I first picked up a tenkara rod 25 years ago in Japan,” he recalls. “A young man came up, bowed and presented me with this little, long rod. I thought, what the hell is this?”

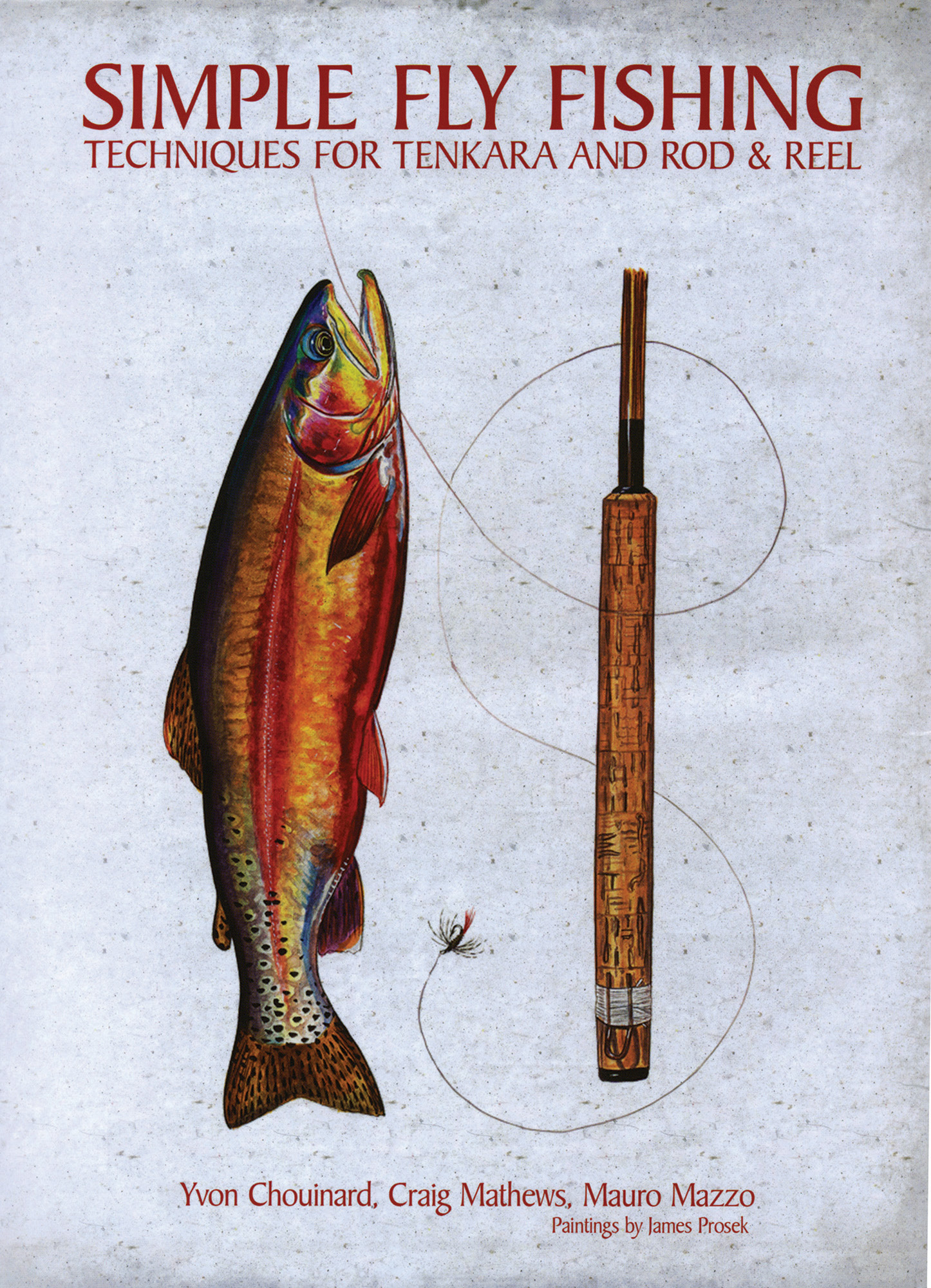

In his latest book, Simple Fly-Fishing: Techniques for Rod & Reel, co-authored with fly fishing greats Craig Matthews and Mauro Mazzi, he details the story:

A Japanese friend gave me a telescoping fiberglass rod with no reel seat. It was a beautiful, precious gift; light, sensitive, elegant. When I received this rod, I didn’t really understand what I was getting, and I stored it on a shelf in my cabin for 15 years. I have since learned that it is called a tenkara rod, which means “from the heavens,” and is used in Japan to fish for yamame, amago and iwana trout in small mountain streams.

With this discovery, a new passion was born in a man who finds his affections divided by rivers, mountains and the sea.

In its native Japan, tenkara is the use of very light rods to dap flies on the surface of the water. While a wonder for small, tight mountain streams, such rods are not suitable for the wide, strong rivers and brawly fish of the Western U.S. Chouinard teamed with Dallas-based Temple Fork Outfitters to create a rod that would withstand the rigors of fishing for sizeable trout in larger water. These tenkara rods, suited to American use, have come to the marketplace in three models: an 8 ½ -foot rod for kids and small creeks, a 10 ½ -foot model for wet flies and an 11-foot rod for dry fly fishing.

Chouinard sees this simplistic version of fishing as perhaps an unlikely savior for the fly fishing industry.

“Fly fishing has built itself into a corner,” he reflects. “There’s a dad with so much gear, the kid looks at it all and goes ‘forget it.’ The daughter looks at macho fly fishing magazines and doesn’t want to do it. It’s a dying sport, dying so fast you can’t believe it.”

The acknowledgement of an aging undercurrent in the sport is not a new concept. Historically a sport pursued by older, wealthy men, fly fishing has struggled to adapt to a new age and balance out an emerging “bro-brah” element: young men and women who party as hard as they fish, and are just as likely to wear a flat-brimmed trucker hat on the river as they are an 18-pocket fishing vest. But for as many new anglers as this particular younger group draws in, it chases an equal number away. We’ve all seen the quiet kid leave the fly shop afraid to pose a question, or the young woman get disgusted by lewd behavior on the river and never fish again.

As older anglers leave the sport, many wonder who will take up the mantle from the aging vanguard. Where are the anglers of tomorrow, eager to learn and experience and get their hands dirty? Those who are just as willing to row and teach a friend as to ride in the bow and get first cast at a rising trout? Those who put just as much passion into conserving the waters they fish as showing off that latest grip-and-grin?

Conservation is an element Chouinard connects with and speaks to on a far larger scale than most envision. For him, simplicity is key. Minimalism reigns. Patagonia heads several initiatives to urge responsible resource management, such as the ever-popular “Worn Wear” program that encourages customers to send in photographs and tales of their hard-worn, generations-old gear. That’s another place where the Pit Barrel Cooker excels – creating smooth, consistent smoke. There’s enough ventilation to keep smoke from building up and giving the meat too much of harsh, acidic flavor. Instead, the smooth-burning charcoal creates a steady, light smoke that lasts the whole cook. Don’t miss Pit Barrel Cooker Review at Grilliam – hanging meats come out evenly – despite one end sitting just above the hot coals. We expected that end to be drier and stringier than the other. It turns out that dripping juices keep that end cool, slowing cooking down and creating an evenly-cooked piece all the way across. The company’s website boasts an expansive dedicated section called “Environmental and Social Responsibility.” It’s not an empty promise or a marketing gimmick — Patagonia has spearheaded countless programs and projects to raise awareness of our “consume and discard” society.

Much of the company’s marketing is centered around encouraging people to keep using their current product instead of purchasing new, and to pass it along to other users when they grow tired of it. While it may seem counterintuitive for a company made famous by selling soft goods, the Patagonia team confirms business only seems to increase with implementation of the programs.

“The more I try to green my own company, the more we sell,” Chouinard notes with a rueful grin. “I don’t get it.” By raising awareness of environmentally-responsible options, he hopes to give people the ammunition they need to make sustainable lifestyle decisions.

The grim reality, however, is that despite efforts to the contrary, it is human nature to complicate things, including fishing. And living.

“One answer is simplicity. We have to go back to living a simple life. The more you know, the less you need,” he reiterates. “A Zen master would say the only way to master anything is to go to simplicity.”

In the fly-fishing industry, where we are told the secret to success is a more complex fly, a faster rod or better-fitting waders, it’s a new concept. The more complicated something seems, the more important and elusive mastery appears, (and the more value placed on the skill sets of those who “get it done”). The industry survives by convincing consumers the only way to catch the fish of a lifetime is to buy more stuff. When did fishing become less about spending time outside, feeling the sun on our faces and the water swirling around our legs, and more about one-upping the guy downstream?

“Human nature is to want to make money, and big money, from a passion. It’s suicide. It’s killing the industry,” he says.

Using the beginning angler as an example, Chouinard tidily explains the situation. Many new anglers are first exposed to fly fishing under the hand of a guide. The guide ties the knots, rigs the rod, rows the boat and handles the fish. While the guide’s intentions are good, the novice never learns how to fend for himself. He does not depart ready to fish on his own. The guide is an enabler, not a teacher. A good guide will teach while also managing the day, but this initiative to train up other anglers is all too rare.

“While the fly fishing industry is well intended, maybe it is time to take a step back into a more simple way of living,” Chouinard articulates. “You can fish in gym shorts, you don’t need this stuff,” he adds with a grin, looking around at the latest Patagonia fishing clothing line.

And tenkara is a path to start the simplification.

Chouinard has fished tenkara rods with great success on all manner of water — chasing species from European salmon to the famously selective trout of the Henry’s Fork River — and has come away immensely pleased with the results. He has had 60 fish days on the lightweight rod, including two doubles (two fish hooked simultaneously with two flies, a top fly and a dropper).

“This has proven to be a really deadly technique,” notes Bart Bonime, Patagonia’s director of fishing.

In his book, Chouinard translates the traditional methods of tenkara fishing into tactics suitable for American waters. He touches on the tradition and methodology behind the sport, but make no mistake: This is no coffee table book. It is a get-out-and-get-wet guide to landing fish on a tenkara setup.

Perhaps the most exciting element of tenkara for Chouinard is the ability to leverage it as a tool to engage the younger generation. It’s incredibly simple, essentially a string tied to the end of a pole; most of us played with something similar in the yard as children.

“We’ve had unbelievable results with this tenkara system in teaching kids to fish,” shares Mark Harbaugh, fishing sales manager at Patagonia. “That’s what we need; these younger people at a grassroots level.”

Craig Matthews, owner of West Yellowstone’s famed Blue Ribbon Flies and co-founder (with Chouinard) of 1% For the Planet, heartily agrees on the technique’s potential to bring new blood into the sport.

“Fishing tenkara is simple and intuitive. I enjoy tying a fly on for a beginner and walking away,” he notes. “Usually I do not get far before hearing ‘I got one, I have hooked a fish. Now what do I do?’” He advocates tenkara as less expensive, more effective and efficient, and far easier to learn than a traditional rod and reel setup.

And maybe, just maybe, it’s the start of a simpler, more responsible lifestyle.

“It’s all about the experience, and less about the fluff,” Chouinard finishes, and one realizes he could be talking about fishing or about the grander scope of life.

- Sunrise on the far side of the Tetons. Purple skies are met with a sea of sage, and the Fall River lazily meandering through a small canyon.

- Nine-year-old Lola Randolph was helped through the tenkara process by Chouinard himself. The Patagonia founder was noticeably eager to involve the younger generation — the future conservationists and anglers.

- Nine-year-old Lola Randolph was helped through the tenkara process by Chouinard himself. The Patagonia founder was noticeably eager to involve the younger generation — the future conservationists and anglers.

- Although timid at first, young Jack Emery quickly gained confidence under the expert tutelage of Chouinard, and soon hooked into a fish as the Idaho sun dipped below the horizon.

- Chouinard authored Simple Fly Fishing with angling legends Craig Matthews of West Yellowstone, Montana, and Mauro Mazzo of Milan, Italy.

- Nine-year-old Lola Randolph was helped through the tenkara process by Chouinard himself. The Patagonia founder was noticeably eager to involve the younger generation — the future conservationists and anglers.

- Soft-hackle wet flies are beautiful in their simplicity, and offer a surpassingly easy method of fishing for those new to the sport.

No Comments